Late last month, Community Board 3 left supporters of Heathers stunned by voting nearly unanimously to recommend a denial of the bar’s liquor license renewal. But was the whole process a waste of time? Two weeks later, the State Liquor Authority — the true arbiter of the fate of businesses that sell booze — renewed the bar’s license with little fanfare, raising doubts about whether it had heeded the board at all.

Just how much stock does the S.L.A put in the community board’s recommendations, anyway? For all the blogosphere’s feverish coverage of dramatic and often-controversial community board rulings, the question is rarely addressed. To answer it, The Local combed through a year’s worth of liquor authority license applications going up to Feb. 2011 (we ignored applications after that date, since many of them are still under review). In that year, we found that the State Liquor Authority consistently granted licenses to bars and restaurants that Community Board 3 had recommended for denial.

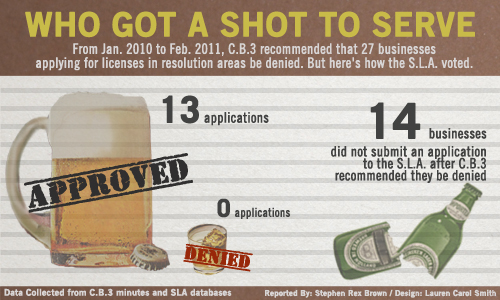

To keep things simple, we focused on businesses within the so-called resolution areas — strips like St. Marks Place as well as Avenues A and B, where the community board has recommended a moratorium on new liquor licenses. Between Jan. 2010 and Feb. 2011, a total of 29 new businesses within those areas asked Community Board 3 to support their applications for beer, wine, or liquor. In an overwhelming 27 of those cases, C.B. 3 recommended that the State Liquor Authority reject the application.

But 13 of those businesses decided to try their luck with the State Liquor Authority anyway, and were granted licenses to sell beer or wine.

Only one — Pho 32 and Shabu on St. Marks Place — was denied by the authority in August of last year, and the rejection had nothing to do with the community board’s ruling, according to records. To top it off, the eatery was awarded a license to sell wine and beer a year later.

Susan Stetzer, the District Manager of Community Board 3, said she wasn’t surprised by the figures. “Just as it is presumed licenses subject to 500-foot rule will be disapproved [by the S.L.A.], it is presumed beer-wine will be approved,” she wrote in an e-mail.

William Crowley, a spokesman for the liquor authority, explained that — especially in the case of wine and beer licenses, as opposed to hard liquor licenses — the authority is bound by law to favor the applicant, provided he or she doesn’t have a spotty record. “The way the statute reads,” he said, “there’s a presumption that we’re going to approve it unless there is a reason not to.”

So does this mean the community board is powerless? Not necessarily. After all, 14 out of the 29 business owners simply did not pursue their license further after failing to receive the support of the board.

“It’s important to note that there is a difference between those cases that fall under 500-foot law and those that do not,” said Mr. Crowley. Under the rule, a bar selling hard liquor (as opposed to just wine and beer) cannot open within 500 feet of three others, though there are caveats. Mr. Crowley said that the businesses that did not apply to the liquor authority could see “the writing on the wall” after being rejected by the board.

“The reason they’re not applying is that they see that we take the community board’s resolution seriously,” Mr. Crowley said.

But is that the reason? A further crunching of the numbers revealed that of the 14 business owners who decided not to go before the S.L.A. after the community board recommended the denial of their applications, 10 were aiming for wine and beer licenses, meaning they would not have been subject to the 500-foot rule.

Interviews revealed another factor in some applicants’ decision to not go before the authority: They were simply misinformed. They thought they were left with no further options once the board opposed them.

“You’re saying that whatever the board says, yes or no, we can still go to the S.L.A.?” asked a stunned Steve Kim, one of the owners of the building at 6 St. Marks Place, which once hosted the short-lived Café Hanover. “Once the board said no we thought, ‘Oh, O.K., we’ll apply later.’”

The owner of T Poutine, Thierry Pepin, told a similar tale. He repeatedly visited the board in hopes of earning its approval. But in April the board recommended that the S.L.A. reject his application — much to the displeasure of his investors. Without his license, and facing the prospect of a long winter when restaurant business generally is down, Mr. Pepin chose to close.

Would he do anything differently, knowing what he knows now? “I wouldn’t have presented myself to the board, probably,” Mr. Pepin said. “I’d just have gone to the S.L.A. and done my thing. I found out way too late that the community board didn’t make the decision.” (It should be noted that although community boards don’t make the final decision, applicants are required to go before them.)

Radouane Eljaouhari, the owner of Zerza, chose not to pursue the transfer of his liquor license to a new location after being denied by the board. Burning a bridge with the board could prove costly in the future. “I didn’t want to be in business and have it be more difficult,” he said.

Still, the question remains: If the State Liquor Authority doesn’t seem to be heeding the C.B. 3’s recommendations about wine and beer licenses within resolution areas, why does the board keep recommending denials? Ms. Stetzer said that the distinction between hard liquor versus wine and beer was only one factor.

“It’s not just that it will be a rowdy bar — that’s not the only issue,” Ms. Stetzer said. “Crowding in front of the business, vehicular and pedestrian access are major issues, too. It does cause problems — but not the ones people are thinking of. It’s not young, drunk frat boys.”

As long as the law allows for new restaurants to easily be approved to sell wine and beer, she said, the lack of retail diversity — one of the board’s signature issues — will not be going away.

“We no longer have retail that supports local residents and businesses. There are few hardware stores, or upscale shoe stores. We can’t buy underwear or supplies for our daily needs,” Ms. Stetzer said. “Many blocks are shuttered all day — they have vacant stores and nightlife businesses. We need daytime foot traffic.”

Ms. Stetzer said that the board plans to vote on a letter expressing these concerns to landlords next month.