(c)2011 Nanci Ezzo, All rights reserved.

(c)2011 Nanci Ezzo, All rights reserved. According to the weather prophets it should have been raining but it wasn’t raining so I went to the Tompkins Square Library to see if I could get Vol. 1 of Proust, but they didn’t have any Proust, and probably never do have any Proust (“Who’s Proust?”), so I decided to take out another novel instead, only to realize I didn’t have a library card, a wallet, or any form of ID, unless you count a cell phone, which I don’t. I did have cash, though.

On to Mast Books, five blocks down Avenue A, but first I encountered… The Racist. A drably turned-out white woman in her thirties, looking like a hipster gone to seed, possibly a junkie. In fact I’d already passed her a few minutes earlier on the way to the library, where I heard her shout racial slurs at more darkly hued people than herself outside the deli on 10th Street, but I wasn’t really paying attention, and frankly it just seemed weird. She looked like a dyed-in-the-wool East Villager. Down on her luck, maybe, but a characteristic member of the neighborhood nonetheless. It was almost unthinkable.

But now she had taken up a position on 10th Street between A and B, where she was busily berating a group of nicely dressed black girls on the other side of the fence inside the park.

“Why do you have so many kids?” she taunted them from the sidewalk, as if in her disturbed mind they had become their own parents. The girls stared at her mutely and with curiosity. White people may say racist things behind closed doors, but they have to be truly bonkers to bring it to the streets of the East Village.

“Why don’t you all go home?” the woman demanded of the girls, meaning Africa, not their parents’ apartments.

“Why don’t you go home?” one of them responded after an uncertain pause.

“THIS IS MY HOME!” the woman bellowed with an unmistakable air of enraged we-got-here-first authority. I decided to move on.

The owner of Mast Books, about whom I’d written for this blog, favored me with the ghost of a flicker of a barely perceptible nod of recognition as I walked in the door – very downtown-New-York cool. I wasn’t in the mood for downtown-New-York cool, however. There was only one volume of Proust on the shelves. It was the wrong one, and I left.

Trudging back up Avenue A through heat and lost time in search of Marcel Proust, burdened by years and remembrance of things past, etc., etc., the next stop was the dingy dimness of East Village Books, but there was no Proust there whatsoever. (“He comes and goes,” the owner said mysteriously.) Then came the The Latest Neighborhood “Moral Dilemma”: Should I head west to St. Mark’s Bookshop in order to support a newly endangered local institution, whose once sullen staff were now comically smiley-faced and friendly, or take a diagonal (the preferred option) to the Strand in the hope of getting a better price? I opted for the latter.

And there, standing and kneeling and squatting and peering intently among the racks of marked-down books outside the store, was Tom Verlaine, the ghostly and reclusive leader of the ancient cult-band, Television, erstwhile King of CBGB, and once upon a time, anyway, the absolute Personification of Downtown Cool. Dressed in a short-sleeved shirt and dark pants, sheathed in his customary Aura of Solitude, he was instantly recognizable. (Spotting Verlaine outside the Strand is by now a total cliché, since he’s been seen there so often.)

Walking straight up to him, I did exactly what I shouldn’t have done and asked him for an interview, knowing my chances of being answered in the affirmative were about 0000.1 percent. Still, I’d interviewed him before, for an hour or so in a coffee shop in Chelsea in 2006, when he last put out a record. Verlaine didn’t remember me, though. “My memory’s just terrible,” he apologized.

One shouldn’t meet one’s heroes, and Verlaine has been one of mine since I was 17. The artist who launches his work into the abstraction otherwise known as the public can have only a vague idea of how it affects people in general, and almost none about how it affects them in particular. What’s unusual about Verlaine is that he seems completely uninterested in the fact that someone might be a fan of his music. Nor does he pretend to be grateful. “More fool, you,” appears to be his attitude. (Or more downtown-cool.)

At least I didn’t ask him the question he must dread most, “When’s your next record coming out?” (Television recorded a new album some time ago; they just never release it, probably because Verlaine prefers reading to touring.) But we did chat a bit, and he was nice enough in his “get me outta here!” way. I mentioned some of the early Television songs, never officially committed to vinyl, that have cropped up on YouTube recently in the form of primitive live audience-recordings.

“Oh yeah, You Tube,” he replied disdainfully, twitching an imperious nostril, as if I myself were the embodiment of the loathsome, royalty-stealing “Tube” in question.

“But those were great songs – ‘Hard On Love,’ ‘Kingdom Come,’ ‘Poor Circulation.’ You could have put out a whole album of them before you released ‘Marquee Moon.’”

Verlaine considered the idea for a moment, pale blue eyes flickering all over the place without ever quite landing on anything. “Yeah, but I think you get tired of those songs pretty quickly.” Ah. Verlaine the perfectionist.

Still angling for an interview, I told him I had a “surprise” for him.

“You have a surprise for me?”

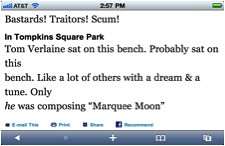

“Yes, I do,” I replied, firmly standing up to my hero. “I published a Twitter poem about you in The New York Times.”

“You published a poem about me in The New York Times?” he scoffed.

“Yes,” I said, pulling out my iPhone. “It’s on their East Village blog. I’ll show it to you!” And then I started frantically scrolling through The Local’s Web site to find it, cursing the slowness of the connection as Verlaine took advantage of my technical problems by moving slowly and crab-wise away from me, rack by second-hand book rack, toward the thronged anonymity of Broadway. It was humiliating. If my phone were to ring – I had a piercingly loud Verlaine ringtone – it would be truly humiliating.

But before he could disappear, I had the poem on my screen. “There,” I said, going over and sticking it in front of him.

Verlaine squinted at it in the sunlight, and seemed favorably impressed (“Kinda like a haiku”), although he said he didn’t enjoy reading about himself. “I like that line, though!” he said, pointing his finger at the the final line of the preceding poem and declaiming the words — “Bastards! Traitors! Scum!” — with relish.

It still didn’t get me an interview. I went inside the Strand, scrupulously avoiding Verlaine, who had also entered the store (not that I knew where he was). They did have Proust but not the translation I wanted, so I walked to Barnes & Noble in Union Square, and there at last I found it, in the “Literary Fiction” section on the fourth floor. (Soon it will be in the attic.) Then I wandered around Chelsea, where a lot of people looked like they were personal trainers, and an equal number looked like they were auditioning for a show on Bravo. Hours later I walked home in an apocalyptic thunder storm. By bed time I was 50 pages into Proust, with only another 3,000 or so to go.

“Say whatever you like about me,” Verlaine had told me as we parted ways, making it absolutely clear that he was not, repeat NOT, going to grant me an interview. “Tell ’em how horrible I am. Tell ’em how I wouldn’t give you an interview. Just don’t say you saw me outside the Strand!”