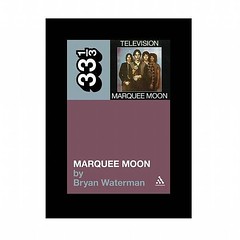

With over 80 titles now published in the acclaimed series “33 1/3” (book-length critiques of particularly esteemed pop records running the gamut from “Electric Ladyland” to “Kid A”), it has fallen to Bryan Waterman, a NYU professor, to dissect Television’s 1977 recording, “Marquee Moon.” His study, which shares a title with the album in question, weighs in at a portly 222 pages (most of the books in the series are much shorter), and will delight both Television fans and nostalgists of seventies punk-era New York. Mr. Waterman explains why the album just might be the prize catch to emerge from the glory days of CBGB.

Since it was released in 1977, “Marquee Moon” has taken its place in rock’s pantheon, and its continuing influence on musicians is well known. But would you expect people in their twenties to enjoy it now?

When my students hear this record for the first time they almost universally agree that it sounds very current, as if it had been released last week. I think that’s partly due to its enormous influence on so much rock and roll, from late seventies post-punk to more mainstream indie rock today. It’s a bit like “The Velvet Underground and Nico” in that way. By now even Verlaine’s vocal style is a bit normalized because he has so many imitators in his wake. We went through a period a few years back where everyone sounded like Verlaine or David Byrne – the Clap Your Hands Say Yeah phenomenon, or even the Strokes, though those comparisons aren’t really fair to Television. Those bands are derivative in a way Television studiously avoided.

In your book, you choose to take a documentarian approach to the making of “Marquee Moon,” emphasizing the artistic, political, cultural and social currents coursing through downtown New York in the mid-1970s. Yet the figure at the center of the book – Tom Verlaine – is a notoriously aloof, individualistic, independent artist who was disdainful of the whole downtown “scene” even as he helped create it. Was this a paradox you thought about in writing the book?

It’s true that Verlaine remained more or less aloof from the scene, even distrustful of it. But his songwriting didn’t emerge in a vacuum. When Television started they were, like a lot of other post-Velvets, post-Dolls New York bands, enamored of mid-sixties psych/garage rock. Television played a significant role, along with Lenny Kaye, in reviving a lot of that stuff, or giving someone like Roky Erickson a renewed hipster cache, here and in London. Almost all early writing about Television compares them to the Velvets, as well. Over time Verlaine stripped out a lot of the obvious influences, which is one reason “Marquee Moon” continues to sound timeless.

But part of what I hoped to do in the book is ground the album historically, and to do so I dug up as much early writing about the band as I could find, both the early version with Richard Hell and the version with [bassist] Fred Smith, which recorded “Marquee Moon” and “Adventure.” What I tried to capture is a sense of the first listeners’ encounters with these songs, live and on record, and those listeners routinely framed them in relation to the downtown scene, both in the way they heard them and wrote about them.

That reflex frustrated Verlaine at the time and still frustrates him today — that he’d be so closely tied to early punk or even to New York or CBGBs. It’s not to say that Television sounded like any of the other New York bands: they all tried to hone unique sounds. But Television’s emergence at the vanguard of an enormously productive and vibrant cluster downtown is part of the story that can’t be ignored at this point.

Aside from what you glean from his music and lyrics, and the basic biographical facts, do you really have any sense of who Verlaine is?

I hope it’s clear from the book that I don’t pretend to know who Verlaine “really” is. Even the idea that we have the “basic biographical facts” straight is a stretch. One thing Verlaine seems to have shared with contemporaries such as [his friend and sometime lover] Patti Smith or Richard Hell was a commitment to crafting an image – and then, paradoxically, inhabiting it in some way that suggested authenticity. So it’s hard to separate the “real” people involved from the images they projected. Hell and Smith may have had more to do with crafting the early Television image than Verlaine did, and Smith in particular seems comfortable inhabiting the character she created for herself 40-odd years ago; but Verlaine made his own contributions to the myth in early interviews and he also has kept the mystique alive by remaining reclusive in the intervening years.

Verlaine took a lot of psychedelic drugs for a couple of years before Television was formed, and then stopped. In fact, he became fiercely anti-drugs. Do you think the nocturnal “urban pastoral” of Marquee Moon could have come into being minus the drugs?

I think of the album as transcendental in a kind of nineteenth-century Romantic sense. References to drugs in his lyrics are often similes: “You know it’s all like some new kind of drug,” from “Venus,” for instance, isn’t the same thing as saying “I’m wandering around downtown high as a kite,” but you think about the latter nonetheless. As a lyricist Verlaine is into perception, and sometimes the perception he represents is as intense as a mind-altering substance. But like Emerson, the speaker in Verlaine’s songs would probably think a drug trip was a cop out. Having said that, I’m sure getting stoned and wandering around what seemed like a medieval city in lower Manhattan in the late sixties and early seventies was a formative experience for a lot of artists.

Where would you place “Marquee Moon” among the great records to come out of downtown New York?

It’s right up there with “The Velvet Underground and Nico” in terms of influence and, I think, its sheer aesthetic power and originality. Nothing else I can think of even comes close. The title track alone puts most albums to shame.