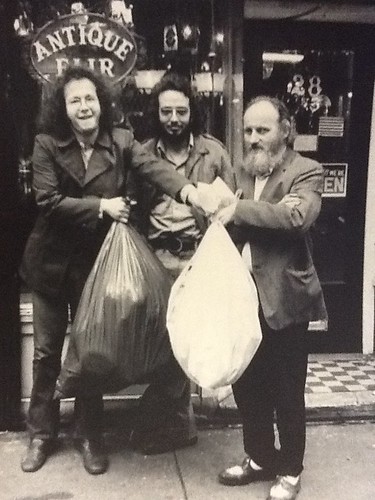

How One-Legged Terry became a member of A.J. Weberman’s circle fades into the mists of memory. Surely, he fit the mold of a Weberman associate with his good humor and dominant, eccentric personality. I met Terry along with a number of people A.J. had acquired from a series of “Dylanology” lectures he had given at Manhattan’s New School for Social Research. This was during a five-month period in 1970 in which I had crossed the country with friends in a (then almost requisite) Volkswagon bus, to spend time with the underground comix community, which by then had assembled in San Francisco.

Terry went by the full moniker of Terry Noble in the United States and Terry Ephraite in Israel, where he had gone to work on a kibbutz after finishing his education. While there, he had been assigned to work atop a hopper that loaded agricultural produce into a machine for processing. His job was to assist in moving the produce from a conveyer that lifted the material to the hopper. After a few days on the job, the platform on which he was standing collapsed, dumping him into the machinery and mangling his left leg. What was left had to be amputated just above the knee. As he remembered his thoughts at the time, they were about the loss of his shoe, one of a pair he had recently bought.

When he sought compensation for his loss, it was revealed that the platform had also collapsed in the recent past, costing another Jewish-American volunteer a leg. Terry surmised that it made more sense to assign an expendable American to the dangerous positions than to fix the underlying fault. Because of the negligence involved, Terry had won a settlement of about $50,000 for his loss.

A traumatic incident of this sort might have colored the ideology of another man, but Terry remained an ardent Jewish nationalist and it was understood that he was back in the United States only for rehabilitation and would return to Israel.

While in New York, being fitted for a succession of ill-fitting artificial legs, Terry used part of his settlement to purchase an early Sony reel-to-reel, black-and-white consumer videotape recorder. It was one of the first I’d seen. He also bought a used camper. Terry’s driving reflected his personality. He would drive his camper around the crowded streets of Manhattan at speeds approaching 60 miles an hour. He especially loved to terrify his passengers. He sped through red traffic lights and zigzagged through streets crowded with double-parked vehicles. It was a testimony to the foolishness of youth and the value of a free ride in New York City that his acquaintances never refused the offer of a lift in Terry’s “wheels,” even after a series of heart-wrenching trips with the maniacal monopede.

Most remarkable about a ride with Terry was his behavior during those frequent occasions when the police would stop him. Typically Terry would quickly jump out of the driver seat, grab his crutches and start waving them, claiming to be a returned Vietnam veteran. Almost invariably, the officer, who was usually young, would be taken aback by the performance of this tall, portly amputee in shorts and a t-shirt, wildly waving his crutches and claiming to be a war hero. Usually this was enough to have the officer send Terry on his way with no more than a warning. If the cop was unmoved by his performance, Terry would escalate to Stage Two and begin unwrapping the bandage around the end of his stump. He would wave it at the traffic officer and yell about the debt the country owed him for his loss. I know of no time that Stage Two did not result in the officer hurriedly sending Terry on his way. At that point, Terry would climb back into his vehicle and rush off into traffic, clearly paying no heed to the warning.

When and how One-legged Terry met Bob Dylan was never clear to me. It was during the period when Dylan was exploring his Jewish ethnicity, which culminated in a visit to Israel and Bob being photographed, looking uncomfortable (as usual), in prayer shawl and yarmulke at the Wailing Wall. Why he had moved his family back to New York City to an apartment on Greenwich Village’s MacDougal Street in easy range of A.J. Weberman’s constant harassment also eludes me. Perhaps they met through the community of Lubavitch Hasidic Jews, in which Dylan had been rumored, amazingly, to have been involved. Time would prove the rumor true when Dylan appeared on the surreal annual money-raising telethon, which the messianic sect produced and broadcast each year on local television. However it came about, One-legged Terry was often in the company of Bob Dylan during the summer of 1971.

Terry was not shy about flaunting his new friend, and soon reports of Terry’s new companion spread among the members of the underground press in Manhattan. Some people met Dylan with Terry on the streets. Others met him at Terry’s apartment near University Place. Terry at this time was using his new video taping capability to chronicle New York’s downtown bohemian community. Prominently featured, of course, was the unusually cooperative Bob Dylan, who either didn’t realize, or didn’t care that Terry was exploiting their relationship.

At one point I had borrowed $10 from Terry, with the understanding that I would repay him on the Wednesday of the next week when a check I had received would clear and the funds would be available. I was sauntering down University Place on Tuesday of the next week when Terry’s camper traveling in the same direction (University Place had two-way traffic at that time) came to an abrupt stop abreast of me. Terry called out to me, “When are you going to pay me the $10 you owe me?” I looked over and saw that Dylan was sitting in the passenger side of the vehicle. I knew that the loan wasn’t due for repayment until the next day, and I was sure that Terry remembered too.

To respond to Terry, I had to lean through the passenger window, right over Dylan’s lap. I realized that the situation discomfited Dylan but I took no notice and explained to Terry that he’d get his money on the next day as promised. As I pulled my head from the window, I nodded to Terry’s squirming passenger and Terry drove off.

I don’t know what happened to Terry’s video footage of this period of Dylan’s life in which the usually reclusive musical genius was so uncharacteristically available. If it were to surface, it would be of interest to both Dylan scholars and fans. Others have said that Terry showed them parts of his Dylan footage, including a piece in which I was the topic of conversation. Terry would occasionally tempt me with references to that conversation, but by then I wasn’t willing to be further manipulated by him, and to see Bob Dylan unaware of how he was being used by Terry had left a bad taste in my mouth. I refused to respond to his prompting and managed to spend less time in his company.

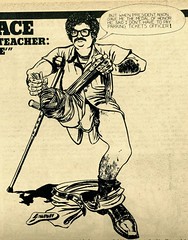

At some point, Ray Schultz, a terrific journalist who worked for The East Village Other and later, the New York Ace – another person who had been involved with Terry for some time – asked me if I would like to illustrate an article he planned to write about Terry’s outrageousness. I agreed and Ray wrote a short funny word portrait that captured One-legged Terry as a character who managed to stand out among the many other determinedly bizarre denizens of New York’s bohemian scene. I illustrated a typical moment of Terry unwrapping and flourishing his stump in the face of a traffic officer, while claiming to be a Vietnam veteran.

We fully expected Terry to be happy with the article, perpetuating as it did the legend he was building for himself. But as we should have realized, it was another trouble-making opportunity. Terry claimed to have been hurt by this characterization at the hands of erstwhile friends. For a short time, people lined up for and against our treatment of Terry. On one side, there were those who felt that our picture of Terry had been undeserved cruelty to a friend. On the other side were those who knew him better.

For all the time Terry was in New York, he never found a prosthetic leg that didn’t cause him great pain. Eventually he returned to Israel, where, I heard, he became a tour guide.

Sometime in the mid 1980s I happened to come across a television news item about the large advances medical technologists in Israel had made in the field of prosthetic legs. Sure enough, there was Terry bouncing around with no discernible limp on one of the new devices. He said that if a leg like that had been available to him after his accident, it would have been a small blip in his life instead of the life-changing trauma it became. He seemed happy.

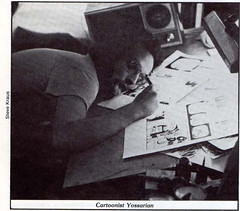

Yossarian, who was born Alan Shenker, is a revered member of the underground comix tribe who, along with Alex Gross, Steve Kraus and Peter Leggieri, is among the few EVO alumni to still call the East Village home. Yossarian got his start on EVO at its sex magazine, Kiss, which was EVO’s short-lived attempt to wrest its once highly lucrative business in sex-based classified ads back from the likes of Al Goldstein’s Screw.

Reports Yossarian:“Don Lewis was EVO’s associate art director and became the art director of Kiss by default. He was next in line for the EVO art director post after Peter Mikalajunas, who soon moved on. When Lewis saw me standing eager to work, he asked me if I had any publication layout experience. I told him I didn’t. Apparently ‘no’ was the correct answer because he asked me to show up the following night to help him put Kiss together. Two weeks later, I was its art director. Kiss may have been a lame-ass periodical, but it was my ticket to ride.”

Yossarian’s drawing and the story Ray Schultz wrote about Terry appear in the February 1-15, 1972 issue of EVO’s also short-lived sister/successor publication, the New York Ace. EVO’s Steven Heller was its art director.

For more on “Blowing Minds: The East Village Other, the Rise of Underground Comix and the Alternative Press, 1965-72,” read about the exhibition here, and read more from EVO’s editors, writers, artists, and associates here.