Underground cartoonist Yossarian (a.k.a. Alan Shenker, Captain Stanley, Mr. Buddy) died on Jan. 14 at Beth Israel Hospital. He had a rare cardio-pulmonary condition known as pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). “Only about 900 cases of PAH are diagnosed in the US each year,” he had told me. “So the pharmaceutical company, specialty pharmacy, and pulmonary clinic all treat you as a big fish that they’ve caught and don’t intend to let go. This means they are highly motivated to keep you going, but it’s an all encompassing program that feels sometimes like joining Scientology.”

A few years ago a PAH sufferer had only about a 15 percent chance of survival for five years, and it amused Yossarian that the drug they used then was Sildenafil—Viagra. “It was PAH patients taking sildenafil having erections that caused Viagra to be prescribed for erectile dysfunction.”

Yossarian was switched to a new drug, Tracleer, which raised the survival rate to 64 percent. But it too had side effects. Although it was keeping him alive, it also made him feel awful most of the time. His head was constantly swimming from the drug’s effects. When he got a pacemaker last summer, he had to stop taking Tracleer and things seemed to go downhill from there.

He wasn’t complaining, though. “Too many people we knew didn’t get to live in my state of disrepair,” he wrote in an e-mail.

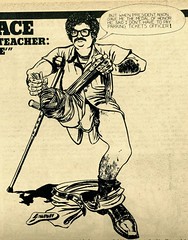

Yossarian lived on St. Marks Place for the last 35 years, and before that on Second Street, between B and C, for several years. An audacious and sharp-witted cartoonist for the East Village Other (EVO), New York Ace, Screw and many other underground papers in the late ’60s and ’70s, he had stopped drawing several years ago—but he was writing. He wrote a piece last year about One-Legged Terry for The Local in honor of the East Village Other (EVO) exhibit at NYU.

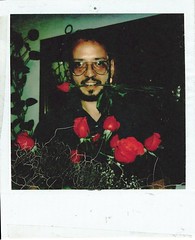

I first met Yossarian at the EVO office on West 12th Street around 1970. I had made friends with two of his amigos, Ray Schultz and Dean Latimer, and they brought me into EVO as a writer. I was a little intimidated by Yo: so intelligent and funny and perceptive, so revolutionary, looking like images of Che Guevara (without the beret) in his green Army pants and jacket.

I remember when a bunch of us went to an apartment on First Street and First Avenue – belonging to a friend of Yossarian’s I believe – and we listened to Dylan’s newly released “Blonde on Blonde.” There was little conversation as we sat there for a couple of hours listening seriously—the way we used to listen to music.

Throughout the early ’70s, he’d often stop by the apartment I shared with his good friend Ray Schultz to schmooze, showing up with food (Big Macs when they first appeared) and refreshments. Then, after a long absence, we ran into each other on the street in the mid-1980s and made a date for him to visit. This time he brought along a stuffed animal—Alf—for my daughter.

After another gap of too many years, I visited his office last year. He looked the same except his beard was grayer and a little longer. His assessment of me: “I would still recognize you.”

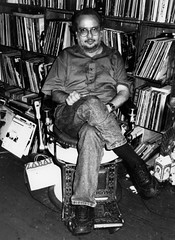

We talked of “the remnants of his life,” as he called it. He went to his office four days a week and visited his sister on Long Island on weekends. As for the future, he didn’t know how long he could continue to climb the four flights to his apartment because of his illness. He wasn’t drawing anymore, but he was writing, and he seemed quite excited by that.

As we had lunch at the Tick Tock Diner, I mentioned I was vegetarian. “But you’d never be a fascist about it, right?” he said.

We talked about a friend who had died, the artist Diana Bryan. He said he took that news hard and told me they had gone together briefly. I never knew that. He was very private about his personal life.

Yossarian would quickly reveal his take on any given situation and find the humor in it, if it existed. He was also genuinely interested in what was going on with you—as long as you hadn’t done something to piss him off. He had no kindness or forgiveness for those who had. But in the end that fell away too. He let go of old grievances. “I’m not interested in shunning anyone anymore,” he recently told his close friend Coca Crystal.

Yo never sold out his principles. Like Joseph Heller’s Yossarian, I’d never expect to see him making a deal with the powers-that-be that would make them look acceptable. He stayed the outsider. As his friend A.J. Weberman said on hearing of his death, “This guy was an honest, talented, trusted revolutionary artist. I knew him well. He stood up against the government for many years.”

Even his foray into publishing, The Razor’s Edge (a magazine dedicated to women with shaved heads), could be seen as a strike against the whole beauty industry establishment; the image of these women was liberating, punk, radical—and for me it also resonated as a screw-you! to the Nazis and a gift to women fighting cancer. And as Mr. Buddy, the name he gave himself as he cut the hair of so many of us (not extreme cuts, by the way), he was looking at haircutting with an artist’s eye. His many identities were not as incongruous as they seemed.

I always thought of him as a loner. What I didn’t know, what his death uncovered, was how many stops he was making along the way, how many friends and loved ones he had, how full and even happy his life was.

Here are some remembrances.

P. J. O’Rourke

I was very sad to hear that Yossarian died. He was a kind and generous friend, though it must be going on 40 years since I last saw him. Yossarian and I lived in the same crappy tenement on East Second Street between Avenues B and C (“Firebase Baker” and “Firebase Charlie” we called them) in 1972, during the worst of New York’s crime wave. The crime was mostly muggings by heroin addicts, and Yossarian was the only sane person in the neighborhood brave enough to go outside between 10 p.m. and 2 a.m. when the junkies needed their fix the most. (After 2 a.m. they were too sick to be dangerous.) Yossarian carried a cap gun to brandish at muggers. One night a junkie tried to hold him up at knife-point. Except the knife was one of those long, dull, springy cheap bread knives.

Yossarian yelled, “I’m going to shoot you!”

The junkie yelled “I’m going to stab you!”

But, of course, Yossarian couldn’t do anything because it wasn’t a real gun. And when the junkie attacked, the bread knife bent double and went “sprong” against Yossarian’s peacoat. Yossarian kept yelling, “I’m going to shoot you!” and waving the cap gun around, and the junkie kept yelling “I’m going to stab you!” and going “sprong” with the bread knife, and this went on for about ten minutes until they both gave up and went home. Yossarian was also the person who said, “Anyone who thinks heroin is bad for the health hasn’t seen a 98-pound junkie carry an air conditioner down three flights of fire escape.”

P. J. O’Rourke is a journalist and author who now lives in rural New Hampshire.

Maryann Gatto Sasaki

I met Yossarian when I followed him home from the 14th Street offices of Screw magazine sometime in 1977. Recently back from a trip to Jamaica with my Drugstore Cowboy first husband, I was hired by Screw as their “mulatto” receptionist. I was an Italian-American girl with a tan.

Initially, I think we just walked home together because we both lived on St. Marks Place, but for some reason I just followed him home every day there after that. I was 19 and he was an impossibly old 32- or 33-year-old. I was trouble, and he knew it, and more than once he tried to shoo me away. But I persisted. The Brooklyn gloss had not quite rubbed off and I think he represented the artist’s life that I wanted to lead. My first husband and I hung with Yossarian. It was the ’70s, so there was much doing and music, but as Yossarian said, quoting Dylan, he was my magazine husband that just had to go, and by the time I was 20 or 21 — and with the dawning of the punk era — I had dropped the husband and found CBGBs.

The relationship between hippies (Yossarian) and punks (me) was interesting in the late 1970s. It was a peaceful co-existence in which the hippies were like our older brothers and sisters. There was a lot of crossover since we had much in common — sex, drugs and rock ‘n roll. Soon after leaving my husband, I was canned from Screw and found myself living on Avenue B among the heroin and the bombed-out buildings. I have to say: I loved it. Money was short and my electricity was turned off. Yossarian turned up and paid the bill. We started going out, and he basically taught me how to be a human being.

Some things he gave me: Bob Dylan, “Brideshead Revisited,” Dashiell Hammett, plenty of pot, diamond earrings and a very short haircut. In fact, he transformed me from a chubby brunette to a slinky blonde. I spent a lot of time hanging with the “old folks” — the 35-year-old hippies — and trying to set up young punk-rock artist types with them, neither of whom were interested in each other. Yossarian and I though, happily, shared many interests. I had a displaced childhood and was not exactly in sync with my generation anyway.

But at that age, in the ’70s, in the Village, with my slinky new body, the very last thing I wanted was a boyfriend who would not let me run around town. So the relationship lasted only about eight months, but we remained friends. Lots of things happened. He got screwed by Screw. He stayed in publishing for a while. I married and ended up improbably at Harvard Law School (something in which he took an avuncular pride). We periodically ate pierogi at one of the ever-diminishing Ukrainian restaurants in the East Village. (We’d seen Meryl Streep during “Sophie’s Choice” eating pierogi at Leshko’s. We thought that was hilarious, and Yo did a devilish Mittel-European accent—kind of imitating Streep practicing her Polish accent by ordering pierogi and kielbasa.) We griped about the neighborhood and the shit-heels that were taking over the city. I always told him he had a lawyer for life because he helped me at my most vulnerable. And I watched him do the same over and over for a whole host of people throughout the years. We spoke when Spain Rodriguez died and e-mailed at the beginning of the year planning to have lunch. It was an enduring and honest relationship.

Yossarian always said after he met me, he never felt young again. As for me, even at 55, Yossarian always made me feel young. He called me Junior and sometimes Sprout and my world was infinitely safer with him in it.

Maryann Sasaki practices law in New York City. She has created a Facebook page in memory of Yossarian @ Yossarian and encourages friends, family and colleagues to share photos, artwork and memories.

Steven Heller

Most vivid for me is the time when we were sharing space together in Screw’s old 17th Street and University Place office that we called the Asylum Press. We each had a separate office. You might recall that he smoked a lot of grass. And in his office he kept every paper match that he used to light his joint. Not only that, he’d line the matches up in precise rows on all available surfaces. It was like a conceptual art piece. Obsessively beautiful. You may also recall he was a Dylan fanatic. He often would pepper one-legged Terry with questions about “Beautiful Bob,” and even go out on field trips with A.J. Weberman to Dylan’s home. Well, put these two things together — dope and Dylan — and you have an explosive situation.

When “Self Portrait” was released, Yossarian immediately bought the LP, ran back to the office, put it on the record player, lit up and began to listen. I could hear it from my adjoining office. Sounded weird. A lot of crooning. Not the old Bob that Yossarian loved so much. Next thing I hear is CRASH, BANG, BOOM. What the hell . . . ? I ran next door to find Yossarian throwing his furniture around the room — the matches flying everywhere.

He hated the album. I’d seen him upset before, but this was crazy. Not scary for some reason, but he was crazed. After a couple of hours, he calmed down, began picking up the furniture and swept up as many of the matches as possible. He put the record back on the player, sat down, lit up a joint and began listening again.

That’s a fan for you.

He was one of my “best” friends at the time. I always felt remorse that after I left the scene, I basically never saw or talked to him again.

Steven Heller is co-chair of the School of Visual Arts MFA Design; Designer as Author + Entrepreneur Program.

Trina Robbins

My biggest memory of Yossarian is when he got busted at the airport, returning to New York from San Francisco in 1970. (In 1970, in a lemming-like migration, all the New York underground cartoonists came to San Francisco. Some of us stayed, others went back to New York.) He had hidden pot in, I think, a tin tooth-powder container! Since nobody else had any money, I went his bail — $200 to the bail bondsman, if I recall. No, he didn’t have to go to jail, and yes, he paid me back. A very sweet guy, I am so sorry he’s gone. And I really hate the feelings of mortality this gives me. Some poet wrote:

Great Caesar’s bust is on the shelf

And I don’t feel so good myself.

Trina Robbins started drawing comics for EVO in 1966, the beginning of her so-called illustrious career; today she writes books and graphic novels from her moldering 107-year-old San Francisco house, where she lives with her cartoonist partner, Steve Leialoha, two cats, and numerous dust bunnies.

Coca Crystal

I am thinking about the Roulette Records party that took place on a boat in the summer of 1970. We (the paper) were invited. I RSVP’d and asked how many people we could get into the party. They said as many as we wanted, so I said 10! When we got there, they would not let us in. Yo was so pissed off he called in a bomb threat. I have kept it a secret all these years. Now it can be told. Charlie Frick and Jackie Friedrich were there with our group and I have a photo of us (or most of us) around a table when we finally got on board.

I lost my East Village apartment in 1970 and the only place I could find (that I could afford) was a walk-up on the fourth floor on East 53rd Street. It was, at the time, less than $100 per month. Yo would often come up, and sometimes I would be late, and one time I found a note that started . . .”waiting for Coca to Crystalize.” He was clever like that.

He was violently allergic to cats and dogs and, since moving to the country, I had both, and it made our getting together more difficult, but not impossible. On one occasion he drove up to Kingston, New York, and took a hotel room for two nights so we could spend some time together.

He was very concerned when I was diagnosed with cancer and visited me in the hospital and called frequently to see how I was doing. (By the way, I am doing fine.) On my frequent trips into NYC for follow-ups at Sloan-Kettering, I would drive right into Herald Square during rush hour to pick him up and then we’d drive down to Chinatown for a meal with friends at our favorite place, Wo Hop. One time the traffic was so bad that I had to do an illegal U-turn on Houston Street. I was almost in tears, but Yo got me through it. He had a calming way about him. I thought that somehow, some day, we might grow old together. I always knew, above all else, that he loved me.

Coca Crystal is a former EVO staffer—writer, secretary, gatekeeper, cable TV star and adoptive mom to her multiply handicapped nephew Gustave Che.

Jackie Friedrich

In July 2010 I came across the Facebook page of one Alan Shenker with a funny, indecipherable profile picture. I sent a message asking if he was the Shenker from EVO. He was and thus recommenced a beautiful friendship.

I was immediately reminded that Shenker also called himself Yossarian or Yo. And I learned that he had adopted yet another identity (alias, if you will): Cap’n Stan. At EVO most of us had multiple names. Jackie Diamond was Coca Crystal. Jaakov, our fearless leader, was called the Arab (pron. A Rab.) And Shenker dubbed me Roxy Bijou.

Memories flooded back: rock concerts in open fields, Electric LadyLand, and mostly of afternoons and evenings spent schmoozing around Jaakov’s desk, particularly on paste-up nights.

Now, we writers were not needed on paste-up nights. We’d completed our jobs. But we stayed. All night. When the office was above the Fillmore East, we went downstairs to Ratner’s, then back upstairs, and at some point, wandered home.

When the office moved to 12th between University and Fifth, I no longer had a New York apartment. I’d given that up with the idea that I’d join one of Wavy Gravy’s bus “communes.” Then Jaakov asked me to cover the Panther 21 trial and the rest is history. Well, Jackie/Roxy history. And on paste-up nights I’d curl up on a desk and fall asleep, reassured by the low hum of conversation coming from the lay-out guys—Shenker, Steve Kohn, Fred Mogubgub and others, including, if memory serves, Roger Tomlinson.

Like everyone at EVO, Roger had his own particular brand of weirdness. When asked if he was going to have a Christmas tree, he gazed into the mid-distance, made a sweeping gesture with his hand, and said he was going to have twelve. A forest. That idea appealed to me. I was less than amused when he illustrated my extremely serious Panther 21 coverage one week with comic animal figures and I loudly complained to Jaakov. Shenker was the only member of the art team to be similarly outraged, though I also had the support of writers Ray Schultz and Dean Latimer.

In the course of catching up, Shenker told me about the “bald woman fetish.” I was both fascinated and repulsed and asked him to explain. He sent me a very long e-mail explaining how he got involved, a beautifully revealing historical document, a faithful recording of aspects of our society at a particular period of time.

I also find that it reveals essential aspects of Shenker: the sentences illustrate his commitment to truth in his art: “getting it right, from the draping of cloth to the way in which hair grows on the human skull.” If you watch the YouTube clips you’ll also see essential aspects of Shenker —his innate gentleness and modesty. So self-effacing and tender in contrast to the preening shavees, his humanity elevates this bizarre fetish into a quest.

One of the last e-mails I got from Shenker revealed another aspect: his Jewish boy from the Bronx sense of humor. One which I, a Jewish girl from Brooklyn and New Jersey, share. I think it came on December 1. I had heard that Spain Rodriguez, who predated me at EVO but about whom I’d heard many stories, had died. I asked Shenker about it and asked if they were friends. Yes, he said, and it’s a great loss.

When I got Maryann’s e-mail on January 16th saying that Yossarian had died I couldn’t believe it. I thought she had mistaken Shenker for Spain. Then I began to realize that she was right and I felt that loss deeply. I also felt robbed. I had been planning to come to New York sometime this year after a much-too-long absence and Shenker was on the top of my list of people to see. I’m only glad we were able to reconnect.

RIP Al Shenker, Yossarian, Cap’n Stan. You did honor to all those identities.

Jackie Friedrich is a former EVO writer who covered the Panther 21 trial—which prompted her to go law school—and the author of several award-winning books on wine, including “The Wines of France: The Essential Guide for Savvy Shoppers” and “A Wine & Food Guide to the Loire,” as well as the newsletter The Wine Humanist.

Claudia Dreifus

Al, and I thought of him as “Al,” not as “Yossarian,” just seemed like one of those quiet nice people who worked hard in the background to make EVO the splendid thing of beauty that it was. He wasn’t a grandstander; just an unassuming artist who seemed thrilled to be working.

One had the sense that he was a refugee from the suburbs and from the conventional life that had been set out for him. The thing that was always so amazing about his work was that this quiet persona disappeared into the world he made on paper. His stuff was so vivid and alive; you’d see his drawings and you knew in an instant that he was special.

Unlike some of the other EVO artists—Steve Heller and Art Spiegelman—I didn’t run into him as life went on. When I saw the piece he did for last year’s EVO reunion on Bob Dylan and One Legged Terry, I was blown away; Yossarian was a brilliant writer too! I mean, he absolutely understood and transmitted everything there was to know about what was really going on.

At the NYU event, he came up and said hello and then he sent me this very sweet note the next day. A few words about context: in my talk I had said I was sort of an odd figure in the EVO world—kind of Margaret Dumont among the Marx Brothers.

Subject: Sorry I missed you.

Claudia,

I’m sorry I missed you at the EVO event. I wanted to tell you that I’ve been reading your TIMES Science page interviews for years with enjoyment. Lest you think it strange, I was part of a cadre of American high school students who was put on a fast path to a science career after the Russians launched Sputnik. I studied electronics at a college level for three years in high school, at the cost of any art training during those years. Stop comparing yourself to Margaret Dumont. I remember you as the sexy blonde who’s head wasn’t screwed onto her neck a couple of turns too many. We, however were the Marx Brothers.Regards, Yossarian

Claudia Dreifus is a writer for the Science section of the New York Times, a professor of International Affairs and Media at Columbia University and the co-author with Andrew Hacker, of “Higher Education?”

Joe Kane

“To live outside the law you must be honest.”

—Bob Dylan, “Absolutely Sweet Marie”

Like his adopted mentor Bob Dylan, Yossarian was a man of many identities: Alan Shenker, teenage techno nerd and later Air Force dropout; Yossarian, original hipster and legendary cartoonist; Yahudi, longtime Screw magazine fumetti caption writer; crusty old Captain Stanley, independent publisher of The Razor’s Edge; Mr. Buddy (hairstyling hobbyist!); and simply Yo, generous bud, twisted wit and, in later years especially, everyone’s fave funny Zen Jewish uncle (he’d even take you out to the ballgame — Mets only).

A Yossarian fan well before I met the man, I had long enjoyed his oft-outrageous, politically incorrect underground comix (e.g., the lighter side of Helen Keller) in The East Village Other and other venues. One of the first mag pieces I ever placed, a cultural analysis of old-school syndicated comic strips, ran as a cover story in New Times circa 1970. In a thrilling stroke of luck for me, it was none other than Yossarian who created a classic cover image of Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy executing a defiant power salute. When I chanced to run into him soon after, little did I suspect that happenstance would lead to a cherished friendship of 40+ years’ duration. I’m glad it did.

You could always count on Yo when you needed a favor or friend. When I was down and burned out in the late ’70s, Yo helped land me a much-needed gig as a Screw editor. He was serving as the tabloid’s art director at the time and over the next couple of years we wore a deep groove into the hallway connecting Art and Editorial via multiple daily visits in a bid to keep each other sane, or at least entertained, in that crazy environment. He always arrived equipped with a quip or two, delivered in a warm, droll rumble that belied the incisive precision of his oft-subversive remarks.

After we received our separate Screw reprieves, we continued to travel down parallel paths. One of my fave activities was hanging around his place of business in the garment center (though schmattes were not his game), sharing laughs and refreshments while his busy VCR whirred away in the background and his colorful clientele trooped through. When I relocated from the city to the Jersey Shore in the ’90s, Yo was a frequent visitor for barbeques (where he usually took charge), boardwalk hikes and home-video marathons (Kubrick, Coppola, Scorsese and Sam Fuller ranked among his filmmaking faves). It was also around that time we both launched indie publications, VideoScope and the aforementioned The Razor’s Edge, respectively (if not respectably), which further strengthened our bond. Those days were probably his jolliest since his halcyon ’60s time; he loved operating his own underground press office and assembling his own zine, from performing art direction chores to drawing spot illos to editing manuscripts to taking on much of the in-house writing. Ever an early adapter—Yo was the first on his block to own a Betamax and laserdisc player—he also contributed a VideoScope column called “Notes from the Internet,” culling choice chat-room rumors and quotes, when relatively few were paying much mind to the nascent, mostly crackpot technology.

Though we saw less of each other over the past few years, due to physical distance and health, we kept up via e-mail, where he proved sharp and funny as ever. I still have many of his missives in my inbox and it’s eerie but sometimes comforting to read them now. I know that, beyond his published work, Yo lives on in the minds of many, where he will continue to entertain.

Joe Kane publishes The Phantom of the Movies’ VideoScope magazine.

Bart Plantenga

From Captain Yossarian to Captain Stanley and Back. Yossarian was so well known by his pseudonym and he had so seamlessly tailored his being to being Yossarian that the name and man seemed inseparable; so much so that many people — even friends — didn’t know that Yossarian wasn’t his real name.

I don’t think this was totally by chance or some hasty decision on his part. He had indeed — in his own way — embraced the glorious absurdity embodied by the probably not-so-fictional main character in Joseph Heller’s “Catch-22” or at least the way this book allowed us to understand our contemporary cognitively dissonant reality.

When Yossarian died, it was different from other friends who had died. I could only conjure up joyous moments of hanging out, bad jokes, laughably horrible movies and cringing levity employed as somewhat effective strikes against the annoying acknowledgment of our own frailty and the fact that we live our lives in one illegal sublet after another.

I think of jokes Yossarian would have told on his way to death’s door. Knock-knock. He’s queuing at Heaven’s Gate, squeezed in between the velvet ropes, the partying hopefuls vying for the attention of the doorman. At the entrance to Heaven’s Gate he’s greeted by a surly bouncer who takes one look at Yossarian, puts his arm across the entrance and says: “Proper attire required.” Ten minutes later, Yossarian returns with a car tire—which, we find out, is the currency that gets him into the club.

If Yossarian is buried in a coffin I would recommend one in the shape of a bathtub and I’d fill it with all of the gag gadgets and weird rubber duckies, strange novelty items like urinating salt-and-pepper shakers, anti-headache soap, a transistor radio shaped like a toilet, stuffed animals that fart when you squeeze them, a cooking apron with fake breasts, tools whose utility escapes you, toys made in countries that may not even exist any more, useless things — if he didn’t have it I would have gotten him the umbrella you clip onto a cigar so you can smoke it in the rain just to hear his chuckle one last time.

His surrounding himself with a dusty constellation of novelty items and gag gifts had something to do with their glib uselessness as if he had purchased them to fully appreciate their cosmic pointlessness, and then later he’d defuse, dismantle and demystify them. Their frivolousness served as a mocking counter-friction to the heavy burden of our everyday lives in a world undergoing rapid decline. He simply assumed that his mission was to distract us from that fact, if only for a few hours, once a month, for about 15 years in my case.

At some point, he gave up on art and cartooning, stopped engaging in a certain kind of critique, avoiding the trappings of cultural depth; not that he was a surfacy-shallow guy or anything. Nothing like that. He had simply given up his membership to the rat race. I remember how I had to bug him for many months and haircuts before he’d let me reprint some of his classic drawings in my book of short stories, “Wiggling Wishbone.” And any ambitions I may have had regarding a “best-of” book of his drawings were always quickly kiboshed with some deflecting wisecrack.

He had a fascination for the simulacrum—although he would have called it something else and I can almost hear his joke where he confuses simulacrum for speculum. He was fascinated by our eternal fascination for empty preoccupation, a state as I understand Jean Baudrillard may have described it, in which we are held rapt by the voluptuous visible and disregard anything beneath the surface. But you had—at least I did—the sense that somewhere along the line, before I met him, he had dived deep and had touched bottom and had, upon resurfacing, come to the conclusion that that bottom was not a happy place to be dwelling. No bottom-dwellers we!

He was profoundly disappointed in progress and skeptical of the powers-that-be who had screwed up any hope that may have been clinging to progress. He had simply let go of something — an urge, anxiety, unrequited love, gravity — so that very little mattered, and in that letting go he could periodically savor or enjoy things like shared laughs with friends.

He took me and XX out to eat probably 100 times; I’m not exaggerating and once in a while we’d get it into our silly heads to treat HIM up there in that restaurant — where was it? — along Long Island Sound somewhere with all the seafood and the gloriously decrepit atmosphere. And OK, I would have that third beer — saying “no” rarely registered with him, he just didn’t hear it — before you could respond, that beer would already be served. That was truly a magician’s magic. But in the time I took to drink that beer he would somehow excuse himself, elegantly out-maneuvering me and XX and he would have already paid by the time I got up to the register to try to pay the bill.

And as we got up from our table, he may very well have left behind a novelty severed finger wrapped in a generous $20 tip on our table for the waitress.

Yossarian the character and Yossarian the friend both embodied the essential black humorist dictum voiced by Heller in Catch-22: “live forever or die in the attempt.”

Bart Plantenga, longtime Yo friend, author of “Yodel in HiFi” and “Beer Mystic,” and DJ @ Wreck This Mess, lives in Amsterdam, a town Yo would have appreciated.

Rex Weiner

A kind of ruthless patricide was implicit in Yossarian’s cover art for the February 1972 issue of the New York Ace. He was close to “the Arab,” as the East Village Other’s editor, Jaakov Kohn, was known, and now Yossarian was one of the defectors from the already tottering EVO to the new paper which I’d cofounded with Robert “Honest Bob” Singer. With this cover he’d created especially for us, Yossarian was declaring his allegiance to the Ace, betraying EVO, to which he’d contributed many cover illustrations, and its paternal leader. EVO’s logo was the all-seeing eye, and for our cover Yossarian had placed an eyeball on a chopping block split by a butcher knife, as if to say, “EVO … You’re DEAD!”

I stared at the image while the artist shifted shyly and uncomfortably from one foot to the other. Alan Shenker was proud of his work, proud to be among a crowd that included R. Crumb, Art Spiegelman, Spain Rodriguez, S. Clay Wilson, and other underground cartoonist stars, and proud of his “Catch-22” nom de guerre. But Yossarian was also Alan Shenker, a nice Jewish boy, and, like all Jews, he was conflicted. How could a nice Jewish boy come up with the outrageous stuff depicted in his masterful pen-and-ink scenarios? Even so, though his butcher knife had a painfully personal target, Yossarian was adding a finely-honed edge to the Ace and every publication daring enough to print his work.

That edge became literal in Yossarian’s self-published zine, The Razor’s Edge, in which the nice Jewish boy exercised, and exorcized, his fetish for the smoothly shaved curvature of the female cranium. Even just a light trim of a woman’s tresses made him happy, as writer Deanne Stillman recalls: “I remember when he cut my hair—for the love of God!”

But I recall staring at Yossarian’s artwork, facing a press deadline, and trying very hard at the age of twenty-two to think like a smart publisher. Never mind the insult to the Arab, which was making Yossarian nervous. I was having doubts that a bloody eyeball chopped in half by a meat cleaver was the right image to win newsstand sales. But I liked Yossarian. He was a wonderful artist and a sweet guy and here he was supporting our nascent venture, giving us his artwork without hope of payment. My doubts were finally swept aside by our editor, Honest Bob, who pronounced it “Brilliant!” and jabbered on about Dadaism, Buñuel, Un Chien Andalou, yadda, yadda. Yossarian was reassured. I just figured what the hell, so we went to press, and Yossarian became the Ace’s ace artist-in-residence.

Yossarian’s New York Ace cover now hangs framed on my wall and I don’t think I’m prouder of anything I’ve ever done. The Arab is long gone, may Jaakov rest in peace, and who cares how many copies of Ace #2 we sold. As Dada daddy Man Ray said: “I have always preferred inspiration to information.” Yossarian’s work taught me that lesson.

Getting his start in the New York underground press of the late 1960s, Rex Weiner now lives in Los Angeles and continues his journalism as West Coast Correspondent for the Forward and Hollywood correspondent for Rolling Stone Italia. This piece originally appeared in The Paris Review.

Loi Kail

Thoughts and memories of Yo have been ever-present since I heard that he died, so you’d think this would be easy to write. It isn’t. Even though I first met Yo almost 30 years ago, and he was a good friend, I find it hard to say I knew him.

He was generous and kind: it was hard to give him anything. He would not take money for haircuts, and I got my hair cut (and dyed) often in my crew cut phases. So I’d hunt for trinkets, bring pastries from Venieros, bake. And I brought a whole bunch of modern dancers into his orbit, because we all wanted short haircuts, and he was simply the best.

I remember him telling me that short hair is really flattering to women because it brings out their faces.

I also remember him saying, “You know, if all the muscles that control hand movement were in our hands, we would have hands the size of baseball gloves!” (He loved baseball). Science-nerd artist.

Mostly though, I think about Yo and my son. Yo took such delight in my son. He really loved him. They say you can really tell a lot about a person by their actions, and Yo really outdid himself with Josh.

When my son’s hair got long enough to need cutting (i.e. toddler age), Yo was his barber. Josh happily sprayed himself in the face with the water bottle during his haircut. He thought it was the fun-est and the funniest thing. Yo thought Josh spraying himself was the funniest thing.

Maybe you had to be there, but for someone as intensely private as Yo was, it was such a treat for me to see him in this way. He brought Josh presents on haircut days. When Josh became obsessed with trains, there was an electric train set one birthday. Yo would bring DVDs: Disney, Loony Tunes, the Marx Brothers and Jerry Lewis. Is this where that Manga (comics) thing started?

About four years ago the haircuts stopped when Yo’s health problems intensified. We made many plans, but most dates ended up being cancelled.

Somewhere in that time, when it began taking Yo longer to return my phone calls, I asked him to please make sure his sister had my phone number, a way to contact me, if/when. Yo’s cousin e-mailed me at his sister’s request . . .when.

Loi Kail is a former dancer and choreographer, Pilates instructor of 20 years and mom of 13 years.

Nancy Naglin

I didn’t know Yo in the early days — I came late to New York and missed that party. But I came to absorb Yo through my connection with Joe Kane. I say “absorb” because Yo was enigmatic, the inner man was hard to know, and he came cloaked in the wrap of legend and, unconsciously, with his witticisms and crustiness, embellished the same.

I went to his office and, admiring his tons of stuff, got the impression he didn’t want me to touch anything. The first time in his apartment (he was showing us the wonders of a VCR — Yo was an early adapter and always bought everything first) I parked myself in his barber chair. “I think you would be more comfortable over there,” Yo pointed to the couch. He took the throne himself.

But when Yo first sent us his wonderful memoir piece “One-Legged Terry,” I immediately e-mailed him to tell him what a jolt it was. One thing led to another and Yo began to tell me of his time in the Air Force. He said he’d enlisted to beat the draft, had been sent to a camp in the Southwest and there, because of an interest in electronics and science, had been handpicked to be trained for a highly technical, covert job. The group that he would be joining, he was told, was in Manhattan.

He was excited and eager for the assignment. First, there was a battery of tests — he was told he passed with flying colors — then medical testing and injections. Yo immediately became deathly ill—he had a complete lung collapse. He said he was hospitalized for the longest time; his life was in the balance. At last, they were able to get him going again, but Yo did not feel well and he still had lingering breathing issues. The Air Force, he said, immediately offered him a cash payment and an honorable discharge. (Yo said the sum was substantial, more money than he’d ever seen.)

Yo, those many decades later, said he didn’t know if the Air Force had inadvertently made him ill — or whether the point of his selection had been the medical “experiment” which went south. Although Yo took the offer, bought a VW bug and the rest is history, he told me how deeply he regretted having taken the money. His silence had been purchased and there was no way he had of finding out anything more about the event, which he believed had been the source of his health problems. That event was a pick-axe in his heart.

Nancy Naglin is an author and freelance writer who works for VideoScope magazine.

Maguy Berry

I was introduced to Yossarian in the mid-eighties. We liked each other’s sense of humor and lack of conventionality. We would usually meet at his apartment, have something to drink, eat, and catch up… I would then move to the barber chair and get one of those striking hair styles that would get me into the latest club without having to wait on line. Yo was known for specific haircuts: usually very short and often very blond or very red. As an artist he was sensitive to color and shapes. He moved from paper and pen (as a cartoonist) to hair and scissors.

Yo’s generosity had no limits. He invited a lot of his friends, including me, once a month, to “refresh” our hair styles, always at no cost. He would also enjoy taking us to some nice restaurants. He made sure to share his favorite ones.

Often, Yo and I took day trips to the Jersey Shore to visit friends. He would then invite us to go to some fancy seafood restaurant.

I will always remember Captain Yankee taking me to a ball game in the Bronx. He carefully explained the rules to me, and ensured that I had the whole American experience including hot dogs and jumbo soft drinks.

He will always be remembered as someone with a very good sense of humor as well as a very generous person. He was definitely a giver.

Maguy Berry moved from Paris to New York over 20 years ago to study fashion design at FIT and still works in the fashion industry.

Diane Shenker (Yossarian’s sister)

Our family is going crazy. They didn’t know about Alan’s career as an artist. They saw him as a very supportive, intelligent and funny family member. But they had no idea about his art. Now they are all finding out he was famous. He compartmentalized his life. He was a very private person who didn’t want to be especially recognized. I think that’s one of the reasons he stopped doing his art. I don’t know if he’d be happy or shocked or sad at all the attention he is getting now.

I wanted him to move in with me as he was struggling with his illness, but he didn’t want to. He told me “I can’t stand the sunshine in the winter in the suburbs. The city has such nice sunshine in the winter.” He found our sunshine depressing.

Alan was always very nonjudgmental and accepting of people. He had his values and respected them and stayed true to them, but he didn’t do that at the cost of hurting anyone.

But he didn’t suffer fools gladly. If you were a friend and you were cherished by him, that says a lot for you. I want all his friends to know that.

Diane Shenker suggests that if you want to do something in her brother’s memory, “think trees.” He loved them and the creatures living in them. “So go somewhere in the dark and plant a tree.”

Lynda Crawford thanks Coca Crystal for her recollections over many phone conversations, which were a great support in compiling this piece, and all the contributors for their help in putting together this appreciation of a man so many will miss.