“My most persistent dream,” he once told Gloria Steinem, “always took place backstage in a theater. I have a very important part to play. The only trouble is that I’m in a panic because I don’t know my lines…”

Truman Capote then elaborates: “Finally, the moment comes. I walk onstage… but I just stumble about, mortified. Have you ever had that dream?”

On the face of it, the horror of stage fright fuels a man’s dreams. That seems straightforward enough; but you wouldn’t need to be Sigmund Freud to find meaning in a writer forgetting his lines. For a writer, such a dream speaks to what one might call the Artist’s Dilemma: the what? why? and how? of the creative act. These are the questions every artist must face. Capote based his career on having the answers to those basic questions.

For his smash hit “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” and the non-fiction blockbuster “In Cold Blood,” Mr. Capote became the brightest of the many stars who formed a seemingly unstoppable literary movement whose epicenter was here, right here, in unstoppable New York. One could say their success was typical of the 20th Century, when Hollywood, and then television, made household names of authors like Tennessee Williams, Harper Lee and Truman Capote, modern masters of the creative act. Furthermore, it didn’t end there.

Throughout the go-go 1960s, Capote continued to dazzle the world from his rounds of the talk-show circuit. That was where Truman and I first met: he was a sensation, and I was a wide-eyed kid addicted to television. Unlike the usual talking heads or dancing-poodle routines, Capote spilled on the nature of art as well as the art of life. These were the things I wanted to know, you see, because I too aspired to live life to the fullest and soar on the wings of art.

By the mid-1970s, however, Capote’s star had faded away, mostly due to his own poor judgment. The elite of New York’s high society were not at all amused to find their peccadilloes lampooned in his latest project, “Answered Prayers.” The resulting scandal was a fire that Capote couldn’t put out, and worst of all one that he couldn’t explain. Overnight he became persona non grata, just when his relationship with alcohol was reaching critical mass.

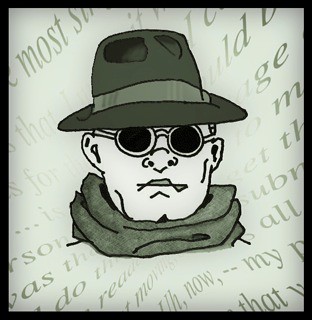

In the aftermath of this social blowback, he became inexplicably drawn to the East Village. Perhaps he sought some gritty, lurid stuff to break his chronic writer’s block. At any rate, by 1978 he had become a fixture at CBGB, his identity obscured by dark glasses and a wide-brimmed hat. There he held forth, anchored to the bar, staring back at the face he found in the bottom of his glass.

That was where I was fated to meet him and this time in person. Like so many young people who aspired to swim in hot artistic waters, I was drawn to the lights of unstoppable New York, and especially the vaunted East Village. Ablaze with musical ambition, I stepped into CBGB with my electric guitar on their weekly audition night.

A variety of punk rockers were milling about, chatting as they waited for the sound-check. Hilly Kristal, the owner of the club, had just promised each one a free drink to be served at any point of the evening. Some forestalled that privilege for after the show. Stage-fright, however, lay heavy upon my tender young nerves, and instead of waiting I strode up to the bar.

“What’ll it be kid?” the barkeep said. A man seated to my right, huddled in a trench-coat, gave me a sidelong glance from under his fedora.

“I’ll have—” I said, giving it some thought, “— a Bloody Mary.”

Truman then tipped back the brim of his hat. In his unmistakable Stradivarius-like voice he drawled, “Are you sure you can handle that, young man?”

There I was, face-to-face with my ancient hero. He eyed my presentation: my skin-tight black uniform, my tousled hair, my guitar slung across my back, his gaze falling all the way down to the boots on my pigeon-toed feet.

I didn’t want to appear presumptuous, so I decided it best to address him with courtesy.

“Well, Mr. Capote,” I said, “this is not my first Bloody Mary.”

He smiled. “Oh, I’m so glad to hear that! Confession is good for the soul, don’t you agree?” His eyes twinkled. He was already quite loaded. “Well. You seem to know what my name is, why don’t you tell me yours?”

I introduced myself. My drink arrived and I took the seat next to him.

“Well, Mr. Milk, I must confess you worry me,” he said with a laugh. “But if you’re still okay after one Bloody Mary, I promise that I will buy you another.” He then made a twirling gesture with his downcast forefinger to signal the barkeep to freshen his drink.

His flirting was enlivening, charming and even hilarious. He was warmed to hear of my father’s roots in New Orleans, and thrilled to hear that I was a fan.

“Wasn’t the movie dreadful?” he asked, speaking of the film version of “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.”

“Terrible,” I said, though in fact it was one of my favorites.

“You know, I have something on my mind,” he said with eyes downcast, his speech beginning to slur, “and I hope you’ll go and tell it on the mountain. I didn’t mean to upset all those people. They… don’t understand… won’t understand…”

I presumed he was speaking of his former friends, they who shunned him for “Answered Prayers.” One can’t help but recall his repetitive dream, where his lines in the play eluded him. Were they unclear? Was his motive not defined, the what? why? and how? miscalculated? For some reason, at his own peril, Capote disregarded those questions. The Dilemma of the Artist then fell upon him like a pile of bricks, to wreak havoc with his once stellar career.

None of this I fully understood at the time, though I did sense that something was wrong with my storied companion. Vodka alone couldn’t make a man so blotto so fast. It put a chill in me to see his foot so heavy on the rail, and it brought out in me something I could never have foreseen: an urge to protect him.

Just as he began to teeter I made a move to assist, but in an instant the bartender reached over to grab his lapels. He guided his head down onto the bar, then covered the author’s face with his hat. I gave the guy a worried look.

“Aw, he’ll be alright,” he assured me, wiping a glass. “Pretty soon they’ll send a car around. You’ll see. Happens all the time.” Then a voice rang out on the public address system. It was Hilly, calling from the stage.

“Next act up!” he bellowed, and motioned my way.

“I guess that’s you, kid,” the barkeep said. “You’re on.”