In the second part of a two-part story, Mary Reinholz speaks with some former residents of Knickerbocker Village.

According to some former residents, free speech became muted at liberal leaning Knickerbocker Village with the onset of the cold war with the Soviet Union, the United States’ former ally against Nazi Germany. During the height of anti-communist fervor, tenants shied away from joining the National Committee to Secure Justice for the Rosenbergs, which author David Alman and his wife Emily helped to co-found while they were living at KV.

“We wanted a new trial for the Rosenbergs, and if not that then clemency,” he said, “But that was a very hot potato in 1951 and we couldn’t get anyone (at KV) to join us. It’s not that people were running from us, just not to us. One tenant,a lawyer and his wife were very sympathetic and contributed (money) to the committee. For us, it was matter of trying to help two people whose lives were at stake.”

David Bellel, 64, a former classroom teacher and retired social studies coordinator for District One on the Lower East Side, lived at Knickerbocker Village from 1952 to 1964. He was an only child, the son of a garment worker. Because his father didn’t belong to any political group, young David wasn’t always aware of the fear that gripped his friends’ parents during the communist hunting years of the Cold War era.

“I was there at the height of the McCarthy era and everybody who was (political) kept their mouths shut or moved away,” he said. “I wasn’t aware of the Rosenbergs until I was an adult. Friends would tell you that their parents belonged to the communist party but never told their kids until it was later revealed them. It wasn’t a matter of being ashamed but a fear of what could happen. I wasn’t aware of the fear because my father never belonged to any organization,” he added. “But you would be hard pressed to find anybody in New York City with a pulse who grew up during the Depression as my father had who didn’t talk politics. I only remember as a kid that he would get into heated discussions with a cousin who was a communist and my father would say, ‘If you don’t like it here, go back to Russia!'”

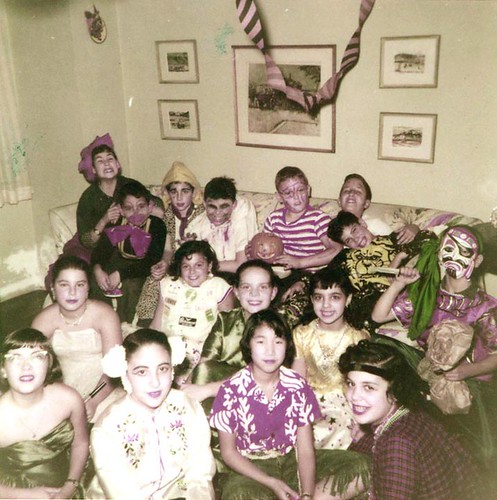

Otherwise, Mr. Bellel, who now lives in Brooklyn with his wife, described an idyllic childhood at KV. He remembers joining, at age ten, a Little League team associated with the LMRC, which stands for the Lower Manhattan Republican Club, and learning what it was like to be part of a team. “For me and my friends it was a time of innocence, collegiality and good times around sports,” he said. “We didn’t have the Internet or video games, so we lived our lives in the streets and in the parks. It was a wonderful opportunity to mingle with all the racial and ethnic groups on the Lower East Side. It was a time when we are all baby boomers and there were lots of kids. If you didn’t like one group, you could find another bunch to hang out with. You had the freedom and knowledge that you were safe within your neighborhood and didn’t have to worry about somebody mugging you for lunch money.”

For the past six years, Mr. Bellel has been in touch with some 100 former KV residents through his KV blog, and has joined in annual reunions with people who attended public school with him, or played on his Little League team.

Also on his blog, Mr. Bellel has developed a “who’s who” of well-known former KV residents, among them “wise guy” Benjamin “Lefty Guns” Ruggiero, a “made man” with the Bonanno family, who was involved in bookmaking, extortion and loan sharking. He was portrayed in the movie “Donny Brasco” by Al Pacino.

Another long time tenant of KV, who asked not to be named for this story, claimed that “capos” from other Mafia families–“but not the top people”– lived at the complex, contending that one associate of the Bonanno organization even acted as a KV building manager.

The demographics at KV have changed dramatically since Mr. Bellel’s youth, when it was dominated by Jewish, Irish and Italian Americans. Of the 3,500 people who live there now, roughly two thirds are Asian, said Bob Wilson, 72, a leader of the Knickerbocker Village Tenants Association.

Mr. Wilson has lived at the development since childhood. He now resides at one of the complex’s 81 penthouses on the 13th Floor of one of the buildings on Monroe Street, paying about $1100 a month for a two bedroom unit with expansive views of the East River and the two bridges. Rooms these days, he told The Local, go for $240 each, well below market value in the rapidly gentrifying Lower East Side (for example, a one bedroom unit, comprising three and a half rooms, would be priced around $840). “A one bedroom walk-up on East Broadway now rents for $3,000 a month,” Mr. Wilson said. “And that doesn’t include the electricity.”

There have been other changes at KV. All the basement rooms–once filled with residents meeting for photography, arts, and ceramics groups–became vacant long before flood waters from Sandy raced through them on Oct. 29. Even a basement theater, where Mr. Wilson used to watch cartoons as a boy, is empty—the result, he claimed, of the Fred F. French company deciding in the 1960s that the basement facilities were too expensive to maintain without raising rents.

The French company sold Knickerbocker Village to an entity called Cherry Green Property Corp. in the late 1970s, but in 2001,the Knickerbocker Village Tenants Association sued Cherry Green Corp. and the New York State Division of Housing and Community Renewal for attempting to deregulate the complex. In 2007, the Appellate Division of the New York State Supreme Court ruled that Knickerbocker Village must remain affordable housing, under Article IV of a 1926 law.

Although the current owners of KV are AREA Property Partners, an international real estate investment management fund, Mr. Wilson insists that the Knickerbocker Village Tenants Association remains a paragon of democracy, with each building writing its own charter and holding its own elections for the association’s 74 representatives. “We don’t have emperors and empresses here,” he explained.

Correction: Dec. 28, 2012 | The original version of this post was revised to reflect a correction. Joseph D. Pistone, an FBI agent who took the name “Donnie Brasco” to infiltrate the Bonanno crime family in the 1970s, was not a resident of Knickerbocker Village.