Allen Ginsberg Bob Rosenthal, front. Back, from left: Gregory

Allen Ginsberg Bob Rosenthal, front. Back, from left: GregoryCorso, Shelley Kraut, and Peter Orlovsky holding

Aliah Rosenthal. 1980. .

As National Poetry Month winds down, let’s hear more from Bob Rosenthal. Earlier, in the first and then the second installment of our interview conducted at Allen Ginsberg’s former apartment on East 12th Street, where Mr. Rosenthal worked as his secretary for nearly two decades, we heard about Ginsberg’s daily routine, his social sphere, and his love of the East Village. Now, Mr. Rosenthal recalls the poet’s romantic life, his way with strangers, and his tumultuous relationship with Peter Orlovsky – fellow poet, former lover, and longtime companion.

Allen and Peter

Harry Smith would be living here and walking through and making films, and Peter Orlovsky’s brother Julius would be here. I would listen to music and then Julius would say, “Bob, would you like me to turn the music off?” and I’d say, “No, Julius, I’m enjoying this music,” and then 30 seconds later he’d say, “Bob, would you like me to turn this music off?” And after a couple of times I’d say, “Okay, Julius, I have an idea: why don’t you turn the music off?” Denise [Mercedes] and her bandmates would try to get Julius to swear and they’d try to trick him but he was so smart and they could never trick him into saying a swear word. It was really kind of zany.

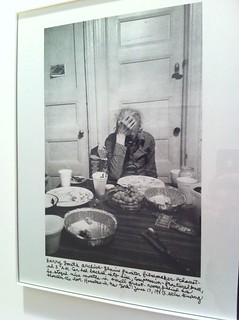

Daniel Maurer A copy of Ginsberg’s photo of Harry Smith at the kitchen table in 1985 now hangs in the apartment’s hallway.

Daniel Maurer A copy of Ginsberg’s photo of Harry Smith at the kitchen table in 1985 now hangs in the apartment’s hallway.It was kind of sweet in the beginning – Peter was making coffee and running in and handing it to me and giving me gallons of apple juice. He was just like that stereotype: had a Volvo wagon down there; he was living upstate and coming back and forth.

Peter had the other bedroom over there, and then later we acquired the 24 apartment and that was sort of the ejection seat. Whoever was breaking up got to live there and then they broke up and some strange things happened. When Denise and Peter were breaking up, Denise ended up there and they were finally done. Peter and Juanita [Lieberman] lived there and then that was finally done.

When Allen moved out, that’s when Peter moved back here [to apartment 23]. He was nuts then. I mean he was always nuts but that’s when all the pigeons were living here. They were walking all over the place. He kept the windows open and he fed them. Peter was true to his art – he was the kind of guy who would drink his first early-morning piss. It was like an ancient mariner kind of thing. I wasn’t sure how often he did these things or he claimed to do them.

I was often taking care of Peter – helping him take care of a parking ticket or get new license plates for his car. In 1984, when Allen went to China, I had to hospitalize Peter. He was very crazy and he had alcoholic-induced psychosis and that’s when he attacked me with a pair of scissors and tried to stab me in my crotch. I loved him, I loved that guy – until he threatened my children. And when he threatened my children, all the love just flowed right out of me like toothpaste out of a tube. I had never experienced any taboo like that but all the sudden I never felt the same again.

I busted him and I don’t know if you remember the Eleanor Bumpurs case – in the Bronx, a big heavy black lady was being evicted. They came to get her and she expired. The police didn’t handle it right. This was the next week. I called the police and Peter’s in here. The police come and Peter was naked with a machete in his hand and he was chopping his own hair off. I mean, he was going in – there was no doubt. And he said, “Let me go get some clothes,” and we said, “No, no,” and he zipped back into the 24 apartment, locked the door: hostage. And that went on – there were cop cars, T.V. stations downstairs. And he wouldn’t do anything.

We finally got one of the Buddhist community guys to come over and he said, “Peter, can I get you something? a bottle of sake?” He was really drunk on sake. And that was the face-saver – he opened the door for the sake and then the police all flew in, strapped him to a chair, and carried him down the stairs. He was screaming like a banshee, playing it up. They got him to Bellevue and I wrote Allen a huge long letter. It was one of the emotional centerpieces of my time here: I was threatened; my children were threatened; I had to take action; Allen couldn’t be here. I always figured Peter did this to me because he knew I would. I mean he had to sober up and he couldn’t help himself, and I think it was a cry for help.

Allen loved it all because it reminded him of his mother’s old episodes. He always kept files on Peter. So he was really the enabler to that kind of crazy behavior and he got a special glow going. I was really naïve at first: when Peter would spend a couple of days in his room, Allen would say, “I figured out what Peter’s doing – he’s drinking,” and I’d say, “Oh no, really? Drinking?” I was naïve. Allen knew he was drinking – Allen knew him for decades. It was just the game.

After this harrowing experience, Allen came back from China and I had read “Straight Hearts’ Delight” and I saw them as the pioneering gay couple and all that, but I always knew that Peter was actually more straight than gay. But still I saw them as a gay couple and I said, “Allen, I don’t understand this relationship.” And he said, “You know, it was only good in the beginning, really” – when they were both really into it.

I get the sense that when Allen first met Peter, Allen just let himself go on Peter. He was like 28 years old and it was the first open sexual relationship he had. Peter accepted Allen, and it was great. That’s when Allen writes “Howl,” and I don’t think Allen writes “Howl” without having Peter. But really soon, Peter in his notebooks is talking about girls on the beach and Allen doesn’t like it. And then Allen realizes, if Peter gets girls then Peter will service Allen, so it becomes a service relationship.

And that was the revelation for me – that it was this one-way relationship: Allen pays, Peter serves and that’s the way it remained. And then eventually I don’t think there was any sexual serving, it was just that Peter would be nice to Allen for a little bit and then he’d get some money. But Peter always had his VA money and after Peter’s drug and alcohol and crack and speed and all that stuff, he would get the check and just get bombed for days and days and days and days and then run out and then sober up hard, and then the last week be self-loathing and remorseful and then the next check would come in and he’d start again. He was bombed, walking up the middle of Sixth Avenue in traffic, yelling his head off. It’s incredible that Peter lasted longer than everybody.

Allen’s Other Loves

He had a lot of boyfriends. He mainly liked straight guys and a lot of them were students. He liked straight guys who would make a special accommodation for him. It’s kind of a problem in the old-guard gay society. Later in his life he actually started to have relationships with gay guys and I thought that was an improvement. There were steadies and this and that and loves. But you know it’s interesting: he would come over and I’d be working and he’d come in with some kid and he’d go into his room and he’d say, “We’re going to go meditate” and I’d say, “Oh yeah, right” – but actually they did. They did both – they probably made love and then meditated.

He was definitely cock-driven – he was definitely on the prowl in a way, but he was not a pedophile. The age of AIDS was actually beneficial to him. Because of his diabetes he had a condition called disesthetia. He actually had a lack of feeling below the waist, so it was very hard to have an erection later in his life. So the point was getting in bed, do more Whitmanic snuggling, and talk about what you’re going to do, and the talking was good and this and that. And so in the end of his life he was doing more snuggling and cuddling and stroking and kind of friendship stuff.

He has some very graphic homoerotic poems. I’ve talked to gay friends about, “Is it really homoerotic? Is it erotic to you?” and some say, “Oh, yeah,” and some say, “No, it’s just self-serving. It’s stupid.” I would probably agree with the latter. I don’t think his “Sapphic Verses” are his best stuff. He wrote a lot. But still, at the end of his life he wrote beautiful poetry.

Allen’s first name was Irwin, so I had moments with Irwin. Like if I was driving him in a rental car – this was before cell phones, nobody could call, nothing could happen, and those would be these private moments. Once he said to me, while we were driving someplace, “Don’t you think if I could just take a pill and be straight that I would do it? I would get married and she would do my laundry and feed me and take care of me?” And I said, “Allen, it’s too late – that’s not happening. Don’t take that pill – it’s not worth it!” And you know what, I think he was just saying that for my benefit, just giving me a clue into him.

Allen in Conversation

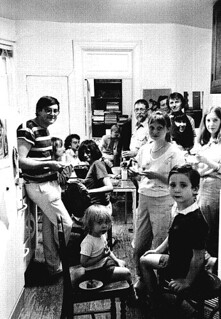

Allen Ginsberg Bob Rosenthal, Roland Legiardi-Laura, Alice Notley, Isaac Rosenthal, Gary Synder, Shelley Kraut, Aliah Rosenthal, Kazuko Shiraishi, Juanita Lieberman and others in Ginsberg’s kitchen at a party.

Allen Ginsberg Bob Rosenthal, Roland Legiardi-Laura, Alice Notley, Isaac Rosenthal, Gary Synder, Shelley Kraut, Aliah Rosenthal, Kazuko Shiraishi, Juanita Lieberman and others in Ginsberg’s kitchen at a party.Allen would do circuits – he would go on the publishing scene, the high-powered art scene (Henry Geldzahler and all those guys) and then photographers and then musicians, and he’d go from circle to circle to circle, so he kept going around and around.

He loved the East Village more than any place in the world. He would walk down the street every day and people would just say hi. They didn’t stop him or make demands or ask for his autograph, they would just say, “Hi, Allen.” And they were just happy that Allen was in their world and part of the neighborhood. When Allen died, I was dumbfounded how many times within a couple weeks people who saw me told the same story: “I said hello to Allen and he said hello to me.” At first I was really puzzled and I thought, what is going on here? Then I realized he wasn’t just saying hello, he was stopping, he was bowing, he was saying hello to the inner bodhisattva in them and that’s who heard them and that’s why it was so memorable – because he got right to the core of their being and said hello to their inner core. It means something.

That’s what Allen was about – his greatest art form after poetry was the art of the interview. If you were coming to interview him, he would hector you: “Do you have your cassette recorder? Do you have extra batteries? Do you have extra cassettes? Are you ready to do this interview? Do you have real questions? Have you thought about the questions you’re going to ask?” Then the interviewer would get nervous and then finally they’d start their conversation and Allen would just open up and be outgoing and not know when to stop. That’s why they’d need extra tapes – Allen knew. And then Allen always demanded that he gets to edit the interview, or he get to look at it. And then he would never have time to look at a transcript and the guy would be like “I have to publish it!” and I would have to get him to do it.

I think that one of Allen’s greatest books is the book of interviews, “Spontaneous Mind.” I think his prose writing is kind of esoteric and it’s a little hard sometimes because of the way his mind jumps or because of his odd punctuation and syntax but when he talks, he’s talking to someone’s bodhisattva so it’s all really direct and he’s really communicating. And that’s why when we did the “Howl” movie – I think the best parts in it is when Johnny Depp is reading Allen’s interviews because I think it just communicates so well and so directly to the audience.

But Allen explained it to me – he didn’t explain how to do it, but it’s something I try to do and I think it’s by being polite, by assuming there’s a bodhisattva in everybody and starting right there. I think that’s how he made peace between people and he could get angry Hell’s Angels to not beat up demonstrators and things like that. He’d just talk to them and be natural. Mailer called him the bravest man in the country. And I think it’s that. Allen’s hero was Myshkin in Dostoevsky’s “The Idiot”: somebody who’s seemingly naïve but he’s just so genuine, and everybody opens up to him because they just can’t help themselves. Allen was really deep that way. He was special, definitely.

As told to Daniel Maurer. Interview edited for continuity. Read the first, second, and fourth installments here.