Earlier this week, Allen Ginsberg’s secretary of 20 years, Bob Rosenthal, shared memories of his former employer – some of which will be included in a memoir he recently completed, “Straight Around Allen.” Speaking to The Local at Ginsberg’s former apartment on East 12th Street, where the two worked alongside each other for so long, he recalled the great poet’s daily routine, his tastes in literature and music, his mail and telephone communications, and his ways with money. Today, in our second installment, Mr. Rosenthal talks about Ginsberg’s social sphere during his two decades in the so-called poets building. Check back tomorrow for still more from this candid interview.

Allen’s East Village

People would always call Allen and say, “Allen, come to my shangri-la in Hawaii,” and here or there. He would never go. A vacation for Allen was coming back and having nothing to do in the East Village. He would often go to the poetry readings at St. Mark’s. He loved the mushroom barley soup at the Kiev. And The New York Times – he just loved it. He hung around Tompkins Square, wrote a lot of one-line poems about skinheads there. And he was a natural. I think because he always felt free here.

It always goes back to: it was inexpensive; he could always keep a home in the East Village no matter where he was, whether he was in Boulder or upstate on a farm or wherever. He would come back here in this room, at this desk here, look at the pile of papers and literally pull at his hair and go, “Oh, karma! karma!” and complain. But then he would stay up all night and go through the mail and start giving me a day’s work to answer these letters.

And I like his poetry about the East Village – “The Charnel Ground” is one of his great poems and it’s all about the people in this building. My friend Michael Scholnick died suddenly and that’s in the poem, and everybody living in the building is in the poem, and I think some of the bums he talks about on Avenue A are still there. Well maybe not, it’s hard to know when they finally go away.

The Houseguests

It was a crazy household. Peter Orlovsky was there; Denise Mercedes, who was Peter’s girlfriend then and started a sort of punk rock band called The Stimulators, was there. So there was a lot of activity here. It was an open house – there were always people staying here.

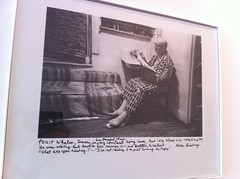

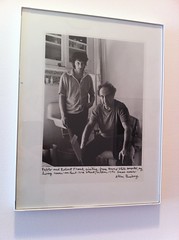

I always thought I was blessed that I was given this opportunity of getting to meet so many people. Dylan and Roger McGuinn in the bedroom, playing music. I talked to Paul McCartney on the phone. I met Dylan in person a couple of times, though I didn’t get to know him or anything. People dropped by – Ram Dass, all these spiritual kinds of people – but mainly the poets: I liked Philip Whalen being here and getting to know him – Robert Creeley, all my heroes.

Gary Snyder came by – he would stay here. Michael McClure. And Robert Frank. Lucien, Robert, and his brother Eugene – and then William, of course – were his closest, oldest friends.

I don’t remember seeing Burroughs here – Allen probably went to see him. He was deferential to Burroughs. He was 8 or 10 years older than Allen. Then when Burroughs went out to Kansas, Allen went to Kansas several times a year to see William. He loved William. The whole thing about the Beat generation: it’s not an art movement, it’s a friendship movement. They were sacred friends and Allen’s pictures, especially the early ones – he was taking pictures of his sacred friends. He didn’t even think of them as photographs.

He once came back from seeing William and said, “I’ve been thinking about gun control. If you have gun control, only the criminals will have guns.” I said, “Allen, that’s what people have been saying forever about gun control!” He said, “Yes, but William never told me before.” Anything William said had a lot of credence. He loved Jack Kerouac. I never met him, but I could tell he loved him.

Lucien Carr, who is the subject of this new movie coming out, “Kill Your Darlings,” was a wonderful old friend and he wanted to stay out of all the publicity. Lucien came by a lot and visited and I know Lucien’s kids and all that stuff. Gregory [Corso] stayed here all the time. I had a lot of interaction with Gregory and he’s a colorful, difficult guy. I was always proper, so if Gregory promised to pay Allen back and he didn’t, I got mad and I wouldn’t do anything for Gregory. That would go on for a little while, and then Gregory came by and said, “You know, you’re not a real poet. I’m poet-man, you’re not, blah blah blah.” But then eventually Allen would say, “Could you give Gregory his money – yes, Gregory.” I have the pictures of his little notes saying “yes, Gregory.” Because he knew I didn’t want to deal with Gregory anymore out of some principled stand. But then I would give in.

I remember walking Gregory to the bank – the Amalgamated that used to be in Union Square. I was cashing a check for Gregory, and I was saying, “Gregory, wouldn’t it be great if heroin could be legal and you could just have your stuff?” And he said, “Oh no, don’t you think I want to clean up?” Just like Allen wanted to be straight, Gregory wants to clean up! It’s five bags a day for decades but no, that’s his dream: clean up, and I want to get over it. Huh.

Diane di Prima would come by a little bit but I didn’t get a sense that Allen was that much into her poetry. He didn’t read the women that well. He liked Anne Waldman but I don’t even know if he read her that seriously – I’m not sure. But he said nice things about Anne because they worked together at Naropa and everything. But he liked Eileen Myles’s poetry actually, I think because she was gritty and earthy and direct.

Later on, the late Lita Hornick set up a reading for Eileen and Allen and I at the Museum of Modern Art, and she got me to read there. She didn’t tell me it was with Allen and with Eileen. The whole thing was fraught with issues for me because I knew Allen liked Eileen and I wasn’t sure if he liked my poetry. And I read and Eileen read and Allen read and actually Allen told somebody else he thought my poetry was really good. So there were times when he liked my poetry.

East 12th Street and the “Boys’ Dorm”

On our website we have one of Allen’s pictures of the block from the ’80s and it looks like a bombed-out city. This was a wild block in the ’70s, too – it was scary. Larry Fagin, after a reading, said to Shelley and I, “Come back to my house and I’ll show you some poetry magazines.” So we walked him back and then we realized he just wanted someone to walk him down the block. Because there was an old abandoned bus garage that was very dark and scary with weird people living in it. 419 was full of junkies and drug dealers. There were two Italian social clubs close to First Avenue, and then the Avenue A side was Puerto Rican gangs. In the summer there’d be gunfire. Big Daddy, who lived around here somewhere, ran a car chop shop right here. They would steal a car, bring it in front of the [Mary Help of Christians] church, strip it in a couple of hours and then in the evening fill it with garbage and gasoline and set it on fire. Everybody was on the streets partying and then the fire truck would slowly back down 12th Street. Everybody would applaud as it put the fire out, and then the hulk would sit there stinking for days. It was wild.

When Allen moved into the building, Larry Fagin said, “Oh, now all the Avenue B artists are going to move in.” It’s kind of true – the building filled up with young poets. To the point where in the ’70s, during the feminist revolution and all that, this became known as the Boys’ Dorm and none of the guys could get dates. It didn’t matter to me – I was married. But a couple of them moved out just so they could start dating. Because the girls who were poets themselves and willing to date other poets, they wouldn’t date anybody here because they figured, “Oh, gossip.” But Greg Masters who is upstairs is still one of those guys.

Very soon after, Richard Hell moved in, and my friend Simon Pettet. And upstairs was Arthur Russell, the musician who played with Allen, and above him Cornelius the outlandish black drag queen who would bring home really rough trade.

One time, Rene Ricard took me up to the roof in some kind of crazed state (I don’t know why I went with him) and he starts getting me to the edge of the roof, saying, “There’s where they do snuff movies.” And I thought, “Oh my god, he’s going to push me down that air shaft. He was crazy on crack, and just a month after that he burned his apartment. But he’s made a recovery of sorts.

Jim Brodey, who was a poet of the generation, stayed for a little while. He started to make a poetry anthology called “437,” of all the poets who had lived here, even just for a summer or a little bit, and it was really a big fat book. It never got published.

When we were in the 17 apartment, we lived right on top of where the Seeligers lived – the crazy Polish landlady who was giving one hour of heat in the morning and one hour of heat in the afternoon in the winter. They had some kind of concentration camp mentality. We had the tenant meetings over their head so we could stomp on the floor and then Allen and Peter would come down and they were the worst (this was before I worked for him, when we were neighbors). They would say, “Oh, they’re nice people, the apartments are warm.” Well, Allen’s was a warm apartment – it gets all this sun. They would say, “Oh no, it’s well heated,” this and that. We stopped inviting them to the meeting.

You would think Allen the great radical organizer … but no, not here. He didn’t want us to be too outrageous, but eventually we did take the building away from Mrs. Seeliger. The court did. The tenants ran it for a while and that’s how Allen got the third apartment.

As told to Daniel Maurer. Interview has been edited for continuity. Read the first, third, and fourth installments here.