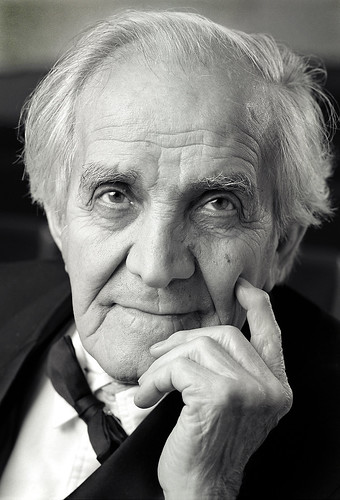

Last Thursday, approximately 100 spectators gathered on the top floor of the Barnes & Noble on 82nd Street and Broadway, expecting to hear Anthony Amato read from his new book, “The Smallest Grand Opera in the World.” Mr. Amato, now 90 years old and more than two years removed from his career at Amato Opera on the Bowery, was under the weather that evening, but the show — as it must — went on without him. Several students from the Manhattan School of Music and nearly a dozen former singers and stagehands exchanged memories of the house’s effervescent owner, from his ability to mimic a French horn to his famous spaghetti and meatballs.

It’s this brand of nostalgia that offers a proper lens with which to read Mr. Amato’s autobiography. Co-written with Rochelle Mancini, herself a former singer at Amato Opera, the book traces its author’s journey from the seaside town of Minori, Italy, to New Haven, Connecticut, and finally to the East Village, where Mr. Amato served as producer, director and owner of one of the city’s most beloved music institutions.

“The Smallest Grand Opera” offers its reader an often fascinating glimpse into the peculiar madness of running an opera house. As he tells it, Mr. Amato’s mornings typically began at 11 a.m., six hours before the start of a day’s rehearsal. Together with his wife Sally Bell, who doubled as Amato’s treasurer, cashier, public relations director and general jack-of-all-trades, the pair spent the majority of their afternoons mapping out their current production and sifting through a seemingly endless collection of props and costumes (Ms. Bell typically handled the fittings, alterations and repairs herself).

Performances proved more taxing still. Because the majority of the opera house’s singers held full-time jobs of their own, its director often had to adapt his production to a missing soprano or pianist; on one occasion, an opera’s scenes were even reordered to accommodate a cast member stuck in traffic. All the while, Mr. Amato, Ms. Bell and their set designer Richard Cerullo worked frantically behind the scenes to make sure that the make-up of the Amato performers was correctly applied and that its stage effects, modest though they may have been, went off without a hitch. All of this seems like pretty standard fare until the reader remembers that Amato Opera was only a fraction of the size of a normal opera house.

Given the number of moving pieces in each production, shows frequently went awry. In one of the book’s more entertaining chapters, Mr. Amato rattles off a list of his company’s most famous gaffes that reads like a collection of outtakes from the Marx Brothers’ “A Night at the Opera.” During the Act II finale of a performance of “The Marriage of Figaro,” for example, Amato Opera’s six-foot, eight-inch bass-baritone managed to dislocate his shoulder while dramatically tossing a stack of papers into the air. Adding insult to injury, Mr. Amato, a five-foot, three-inch tenor, took over the lead role only to have the original Figaro return to the stage in the final act with his arm in a sling. In a separate production of “Madama Butterfly,” an elderly woman wandered onto the stage before a pair of geishas could escort her to the restroom at the rear of the theater.

Moments like these illuminate the basic spirit of the Amato Opera and its singers. Lacking the finances of professional venues like the Metropolitan Opera, Mr. Amato’s productions were often held together with Velcro and safety pins — sometimes quite literally. Quoting his wife, Mr. Amato writes: “Without safety pins, there is no opera.” Including its operas-in-brief, which its singers performed for public schools across the city, Amato Opera staged upwards of a 100 performances a year for more than 60 years — a figure made all the more spectacular by the company’s limited resources.

While Mr. Amato devotes much of his story to his dual love for Ms. Bell and the works of Giuseppi Verdi (Amato Opera’s patron saint), his opera company’s enduring popularity reveals a third narrative buried between the book’s lines and chapter breaks. “The Smallest Grand Opera” quietly reads like a Horatio Alger-story, replete with a hard-working hero whose dedication and good will enable him to realize his own version of the American dream.

Like so many self-published autobiographies, Mr. Amato’s sometimes sags over the course of its 250 pages. He bombards his reader with excerpts of his show’s more favorable reviews and the block quotes tend to gum up the narrative (one also can’t help but wonder if he doth protest too much). The book’s authors also miss a few opportunities to really dig into the culture of the East Village and how it transformed over the course of the nearly fifty years that the opera was situated on the Bowery (during the Barnes & Noble reading, Ms. Mancini revealed to The Local that Amato’s singers liked to pretend they were the reason the cameras popped in front of CBGBs).

More problematic still is Mr. Amato’s depiction of the family saga that engulfed his opera house in the year before its closure in 2009. Walking his reader through the fallout with his niece Irene Frydel Kim, who was the heir apparent to Amato Opera before she was removed from its Board of Directors, Mr. Amato seems eager to portray himself as the victim of manipulation and legal machination. While his account of events may be true, it comes across as oddly self-serving, particularly with a lawsuit still pending (at his lawyer’s request, Mr. Amato has declined comment on the matter).

Despite these foibles, Mr. Amato’s book proves every bit as vital as his opera productions. In the tradition of Luc Sante’s “Low Life,” “The Smallest Grand Opera” helps preserve a piece of the Lower East Side that might have otherwise been lost to history. If only its author would reveal the recipe to his tomato sauce.