You’ve heard one former NYU student’s memories of working the door at Limelight (the documentary about the club opened tonight at Sunshine Cinema); now let Jane Bernstein, an NYU alum of an earlier era, regale you with stories of working the box office at a still more legendary club – the one and only Fillmore East.

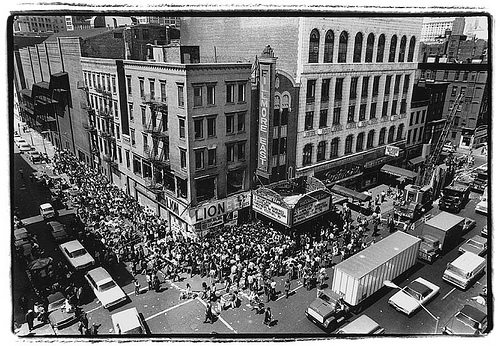

Amalie R. Rothschild A crowd gathered in May 1970 when tickets went on sale for Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young.

Amalie R. Rothschild A crowd gathered in May 1970 when tickets went on sale for Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young.As I prepare for the Fillmore East’s fortieth reunion on Saturday night, I wish I could remember more about all the music that played there. From opening night on March 8, 1968 to the final concert on June 27, 1971, the best-known performers of the era (The Doors, The Who, Jefferson Airplane, Santana, Joni Mitchell, Elton John, The Allman Brothers) were on the stage twice each Friday and Saturday night, at 8 p.m. and 11:30 p.m. Only the Rolling Stones and the Beatles bypassed the legendary theater on Second Avenue and Sixth Street for stadium-sized audiences.

I heard nearly all of these performances because I worked at the Fillmore, first as a “candy chick,” then in the main office, and then as a “box office crazy.” I spent five days a week in our narrow “shoe-box office,” with its graffiti-covered walls and 50-pound boxes of Hershey’s Kisses, which we distributed by the handful to customers.

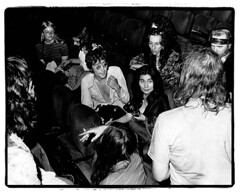

The holes in my memory make me a terrific disappointment to my daughter, who is hungry for stories from this era. She was outraged that I couldn’t recall Jimi Hendrix practicing “Purple Haze” and could share no details about the night John and Yoko showed up. She couldn’t believe I forgot about Ike Turner waving around his gun backstage.

Partly it’s my age, and partly it’s that so much happened, on stage and off, on any given night. I can remember waiting in what someone called “hysterical nonchalance” for Bob Dylan to appear one night when the Band was playing, but I’m sure on that same night there was a kid hallucinating in the balcony, and a romantic entanglement in the narrow box office, where we slid past each other, belly to belly.

Indeed what I remember best are the people who worked at the theater, members of “the Fillmore Family.” And we were a family, in a way. One year, instead of spending Thanksgiving with my parents in New Jersey, I celebrated the holiday at a long table in the lobby of the theater with others who felt more connected to the Fillmore Family than any family that came before. I sat beside Janis Joplin. I do not recall saying “hi,” or “pass the cranberry sauce.” I only remember my parents’ generous acceptance that I chose to have Thanksgiving at the Fillmore, and what I wore – a purple felt hat with a paisley scarf. Decades later, I gave my daughter the purple hat, as if to apologize for forgetting about “Purple Haze.”

I had never been a joiner or a fan before I started working at the Fillmore. I liked my classes at NYU, where at the time I was an undergraduate, but I felt no allegiance to my school. On the other hand, the Fillmore was perhaps the most democratic community I’ve ever known – made up of artists and innovators who would achieve great prominence, and also mellow, inarticulate people of limited abilities. There was a stagehand whose plays were produced by Joseph Papp at the Public Theater, and then a dimpled usher with waist-length hair, who nodded, said “wow” and “far out,” rocked slightly, giggled, and never once said anything else.

Lauren Carol Smith Jim Power’s mosaic for the Fillmore, in front of the building’s current occupant, Emigrant Bank.

Lauren Carol Smith Jim Power’s mosaic for the Fillmore, in front of the building’s current occupant, Emigrant Bank.Though we were a family, we were not a cult. Rather than being part of “rebellion” as the parents or the media thought, we were drawn in by the music, and united by our unspoken values. Nor were we a patriarchy, though Bill Graham, the charismatic and volatile owner, was certainly a presence when he was in town.

Bill, who had been lured back to New York three years after opening the Fillmore West in San Francisco, was awesome in every meaning of the word. He wasn’t just a gifted concert promoter – he was utterly passionate about music. He’d book a headliner he thought would sell tickets, and on the same bill he would put performers his mostly young audience wouldn’t otherwise have heard. Miles Davis opened for Laura Nyro (and later for Neil Young). You bought a ticket for Ike and Tina Turner and also got to see Mongo Santamaria and Fats Domino. He never let us forget that Chuck Berry was a rock-and-roller well before Van Morrison.

Sometimes it was daybreak before the theater doors were locked. When the Grateful Dead came to town and the acid flowed freely, the sky was often light before their endless, trippy music finally ended. I remember buying a bagel at Schacht’s one night after work and wondering if it was my dinner or breakfast.

We felt privileged to be working at the crusty old theater, with its layers of history. Originally built as a Yiddish Theater in 1926, it was a Loew’s Commodore in its next incarnation, and then the Fillmore East. The building had been “updated” with signs and warnings, rather than renovated. If you stopped to look, you could see the former splendor – Corinthian columns, painted murals, a proscenium arch. Stage lights were set up in the box seats. Backstage, there were platforms for the massive amount of equipment used by the light show. A green room had been transformed into a “Bummer Palace,” where kids on bad trips could be talked down or taken for medical treatment.

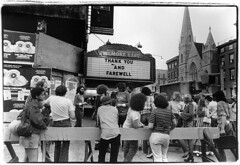

It lasted less than three years. By the time the theater closed, the neighborhood had gotten rough. Hard drugs fueled ugly scenes. Ultimately, superstar performers weren’t interested in playing four times a weekend for an audience of 2,700 when they could earn vast sums for one show at Madison Square Garden. The first sign of the change in my insignificant corner were the ticket buyers. In 1968 they’d been delighted by those foil-wrapped Kisses; by 1971 they complained bitterly about not getting enough. Then the rats arrived – ugly harbingers of change – and chewed through the boxes of chocolate.

A hundred people will show up at a Midtown club for our reunion. Josh White will do the light show, just as he had in the early days of the Fillmore, and we’ll see a video tribute sent in by two former Airplane members. We’ll exchange stories about the music, the drugs, the post-show breakfasts at Ratner’s, the 50-cent soup and bread at B&H. I regret remembering so little about Frank Zappa, but I can still taste the challah Lena made on Fridays, still warm when I picked it up on the way to work at 11 a.m., with an occasional crunch of eggshell.

I suppose we’ll talk about the weeknights when Bill gave over the theater to neighborhood groups or for benefit performances. (Will anyone remember that Pete Seeger opened for H. Rap Brown and Bernadette Dohrn at a fundraiser for “The Guardian”?) We’ll have a moment of silence for Bill (Wolodia Grajonca by birth), his tragic history unimaginable to us then. He seemed so old at the time, but he was only sixty when he died in a helicopter accident in 1991. All of us are older than that now.

When I pushed open the Fillmore’s broad doors all those years ago, I walked into a place where I felt I belonged, a place where status and money meant nothing, where there was no hierarchy or social anxiety, no pressure to perform or succeed. My most fervent wish – my only one – was for a sold-out show. Then I could lock up the box office, stand in the back of the theater and wait to for the music to fill me. How glorious it was in all its forms – how transcendent.

Jane Bernstein is the award-winning author of five books, among them the memoirs “Bereft – A Sister’s Story,” and “Rachel in the World.” Her essays have been published in such places as the “New York Times Magazine,” “Ms.,” “Prairie Schooner,” “Poets & Writers,” “Self,” and “Creative Nonfiction,” and her screenwork includes the screenplay for the Warner Brothers movie “Seven Minutes in Heaven.” She is working on a new novel, “The Face Tells the Secret.”

Related: Read Stephen Rex Brown’s retrospective of the Fillmore East and see more of house photographer Amalie R. Rothschild’s photos.