Many students moving into NYU’s Palladium dorm this week likely had no clue that their new East 14th Street address was, until 1998, home to a notorious nightclub of the same name. Now a documentary by Billy Corben, director of “Cocaine Cowboys” (a cult-hit chronicle of the Miami drug scene in the 1980s) revisits the era when the club was a fixture of New York City nightlife, and when its owner, Peter “King of Nightlife” Gatien, was at the heart of two dramatic court cases that represented a larger fight between the hedonism of the late eighties and the Giuliani-induced law and order of the mid-nineties.

Per its title, “Limelight” focuses primarily on the most famous of Mr. Gatien’s four Manhattan clubs. Limelight was previously the subject of a movie (“Party Monster”) and a book, “Clubland” by Frank Owen, who is interviewed extensively here. Those works explored the druggy parties that promoter Michael Alig (interviewed here from his prison cell) threw at the club, and his killing of “club kid” Angel Melendez.

“Limelight” focuses more tightly on the story of Peter Gatien, the club’s owner. Mr. Gatien used $17,000 of insurance money from a teen-age hockey injury that debilitated one of his eyes (hence, his trademark “sinister” eye patch) to open first a bar in his native Canada, then clubs in Miami and Atlanta, and eventually four clubs in Manhattan. He has maintained a relatively low profile since he pled guilty to tax evasion charges in 1999, declared bankruptcy, sold his clubs in 2001, and was deported in 2003. (He closed Palladium and sold it for a paltry $500,000. It was eventually leveled to make way for the dorms.)

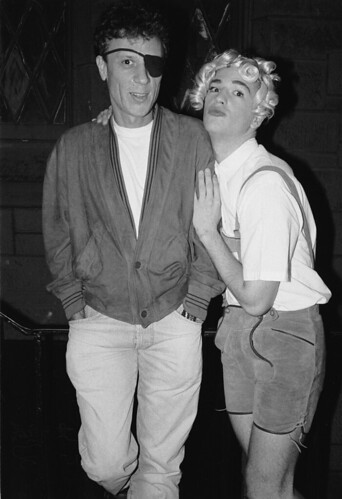

In “Limelight,” Mr. Gatien is prominently interviewed wearing far less sinister Ray Bans-style shades and maintaining a mix of jadedness and charisma reminiscent of another drug dabbler turned family man, Anthony Bourdain. He comes off not as the evil mastermind behind “drug supermarkets” that federal prosecutors claimed he was (he was acquitted in 1998, as described during interviews with his attorney Benjamin Brafman), but something between an affable everyman and a nightlife martyr not unlike the clubgoer who arrived at one of Limelight’s first nights pinned to a crucifix. It’s no wonder: one of the film’s producers is his daughter, Jen Gatien (“Holy Rollers,” “Chelsea on the Rocks”).

Is it thanks to Ms. Gatien that we see adorable photos of the Gatien family and don’t hear about the hotel orgies her father is said to have hosted? (Mr. Gatien does cop to the occasional cocaine bender at the Four Seasons, but insists he never ingested drugs at his own clubs.) Whatever the case, the film’s worst flaw isn’t its one-sidedness (in all fairness: the federal prosecutors who tried Mr. Gatien declined to be interviewed, as did the undercover agents that dressed as “club kids” in order to make drug purchases.) Rather, it’s the fact that “Limelight” fails to bring its namesake subject alive in the same sensational and exhilarating way that “Cocaine Cowboys” did the Miami drug scene. Despite the use of trippy audiovisual effects, the film more closely evokes an Ecstasy comedown than it does a high.

Occasionally, “Limelight” offers a taste of the club’s gleeful depravity. Michael Alig, looking surprisingly healthy and chipper – though not exactly “fabulous” – in prison, at one point tells about a game called “What’s My Line,” in which clubbers ingested mystery lines of white powder and had to guess whether they had just snorted cocaine, Special K, Ecstasy, or Rohypnol. Michael Caruso, a.k.a. Lord Michael, a promoter who helped techno spread from London to New York (with rave culture to follow), tells of mixing 200 pills into an “Ecstasy punch.” (Mr. Caruso chose to testify against Mr. Gatien after he was arrested for drug dealing, but insists here that his boss never asked for a cut of his drug business, or funded it in any way.)

However, these inside stories are few and far between. Instead of the wild yarns from club kids that Disco 2000 alumni might be longing for, we get the usual kvetching about the state of nightlife from the likes of Steve Lewis, the director of Mr. Gatien’s clubs who was convicted of conspiracy to traffic narcotics and is now a club designer and curmudgeonly nightlife blogger. Instead of music that evokes the time (like Jan Hammer’s score did so well in “Cocaine Cowboys”), we get generic beats from Fast, the soundtrack’s composer. (Why not use livelier cuts from DJs associated with the club?)

Though there is a fair amount of archival footage here, there just isn’t enough to satisfy the nostalgic, or to truly impress the uninitiated — which is rather strange given how much the club kids loved to document themselves. Instead we get photo animations that aim to be cute but quickly become annoying. The Limelight often appears as a digital simulation. (The filmmakers couldn’t get more real-life footage of a club that was open into the aughts?) And voiceovers done in the style of newscasts quickly become grating. (More amusing are the clips of Phil Donahue blowing America’s minds with club kids.)

For New Yorkers who are all too familiar with the sorry state of nightlife, the film is only bogged down by its somewhat academic attempts to track the decline of club culture owing to AIDS, the Ecstasy crackdown, CompStat, and the Nuisance Abatement Law.

Ultimately, Mr. Gatien was forced to close Palladium and sell it for a paltry $500,000. It was eventually leveled to make way for the dorms.

The film ends with the fallen club king waxing patriotic about America, land of opportunity. But first we’re told that Mr. Gatien, who is still exiled in Canada, was denied a pardon by Governor David Paterson in 2010. What we’re not told, for some reason, is that Mr. Gatien, who says he left the U.S. poorer than when he came, managed to open a four-story nightclub, Circa, upon his return to Toronto (it has since closed). That club isn’t mentioned in press materials, either, though a glowing bio of Mr. Gatien does mention that he’s “determined to create a series of successful state-of-the-art entertainment, dining and lodging establishments that will bring worldwide acclaim to hi[s] Canadian hometown.”

Maybe “Limelight” can help hook in some investors, but it remains to be seen whether it will hook in theatergoers when it opens September 23.

Have any Limelight or Palladium memories? Share them in the comments.