Dentists are always memorable. Anyone who gets paid to poke around in your mouth is bound to be.

I have had two dentists in the East Village. The first was a man from the Indian state of Gujarat who chewed obsessively on the carcinogenic Indian palate-cleanser known as paan. I will call him “Dr. V.” He is gone now, put out of business after his landlord doubled the rent on his miniscule store-front clinic in Alphabet City. This was a minor tragedy for the neighborhood, for if you had a rotten tooth and no insurance – even no money – Dr. V was your go-to guy.

Dr. V had learned dentistry in India under what he called “the British system,” which he held in high regard, although his feelings about the British themselves were mixed. He was a man of small, delicate stature, about 60 years of age, and had lots of opinions and was keen to share them.

Most of the time, a dentist is someone to whom, by definition, you can only listen, not speak – your side of the conversation being confined to gagging sounds that you hope will not involve drooling. So it helps if the dentist is entertaining. (I did once have an East Village dentist – only briefly, thank God – who talked about nothing but the minutiae of politics in Albany. That was truly abysmal.)

Dr. V.’s conversational canvas was large, and he would lay down the law on every subject imaginable. But I felt he cared about me. He always gave me advice, seemed to look into my mind and soul as much as my mouth, and often he made me laugh – if not always on purpose.

“Why laughing?” he would ask sharply whenever this happened, his bulging brown eyes staring straight into mine. I couldn’t tell him that it was at least in part because of his comically rich Indian accent (there was no getting around that) – one that had become even more comical to me in as much as I regularly regaled my friends with an imitation of it.

There was also the fact that whenever his wife called – which she did about every ten minutes – he would answer, “I cannot speak now I am with patient!” and slam down the phone. Then he would become momentarily disgruntled and complain about how she constantly hounded and harassed him, which I rather doubted, even if she did call an awful lot. But once, when he was whittling away at one of my problematic teeth, applying and reapplying a piece of carbon paper as we made our way through the tedious process known as the “bite test,” I asked him if he wasn’t “afraid” of whittling the tooth down a little too much.

“Brendan, I am not afraid of anything,” Dr. V replied with deadly earnestness. “Except my wife.”

After Dr. V’s forced departure from the neighborhood, I went to see an older dentist on its wealthier fringes, who I will call “Dr. L.” Dr. L’s practice was more orthodox, more American (he was American) and certainly more high-tech. (His office was clean, for a start.) He was a nice man, a polite man, a successful man; but not what you would call a physically attractive man.

Dr. L was scrupulously liberal and progressive in his politics. His views on women, however, were quite antiquated, although he had no idea this was the case. Had he been informed it was the case, he would have been absolutely mortified.

This was in stark contrast to Dr. V, who, being very much his own man, could have cared less what anyone might think of his views on women. “They are my views, not yours!” would have been his attitude. Oddly, this made him more American in the traditional free-speech sense than the 21st century New Yorkers he lived among, most of whom had been cowed by speech codes and multiplying “sensitivities” into weighing their words carefully. He was also utterly indifferent to the prospect of death. Everything was in “God’s hands,” and there was no point in worrying about any of it – or so he claimed. A visit to his office always felt strangely like a session with an unorthodox but skillful therapist, even if your jaw ached afterward.

Whereas Dr. V worked solo – free of bureaucracy and red tape – Dr. L had an assistant, a dental hygienist whose family had come from one of the more ferociously oppressed countries in the former Communist bloc. One day she was missing from Dr. L’s side (he explained she was off that day) and, in her absence, we talked about her for a bit – the degree she was studying for, and so on. I mentioned that she was very pretty.

“She is very pretty,” Dr. L agreed. And then, in some astonishment, he added, “And she’s smart, too!”

Something about the way he said it suggested that this was a combination of qualities hitherto unknown to him. Worse, as I discovered later, he would praise her for being pretty and smart when she was standing right next to him. Fortunately, his assistant didn’t seem to hold it against him. No doubt she had him accurately pegged as a man almost half a century her senior with a blind spot on this particular subject.

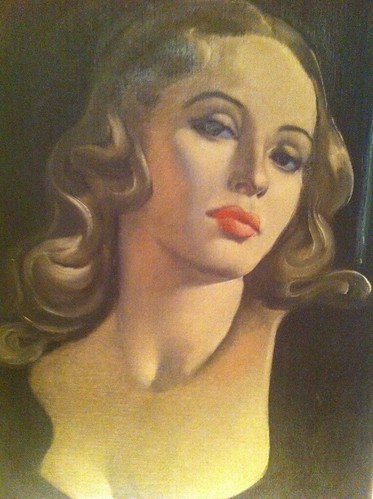

Dr. L, I realized, was quite keen on his young hygienist, and thought she was more than merely “pretty.” In his opinion, she was beautiful. She was also nice. On the afternoon when she was absent from the office, he said something I’ve never forgotten.

“You know, Brendan,” he told me as he prepped a syringe and sorted through a sadist’s dream of steel implements on the tray in front of me. “I haven’t had the opportunity to meet many beautiful women in my life, but it’s really a pleasure to come across one who doesn’t act as if she’s doing you a personal favor just by speaking to you.”

There was only a trace of rancor in the way he said this. His tone was almost as matter-of-fact as if he’d been talking about cloud formations or the price of butter. Apparently, this had been the reality of his life as he perceived it. A life pretty much devoid of beautiful women, and almost exclusively devoid of kind beautiful women.

Having delivered himself of this brief confession, Dr. L picked up a syringe, deftly slipped the needle into my gum, and slowly flooded it with Novocain. Then he chose one of the sharp steel tools from the tray, told me to open wide, and began to do what he knew how to do best.