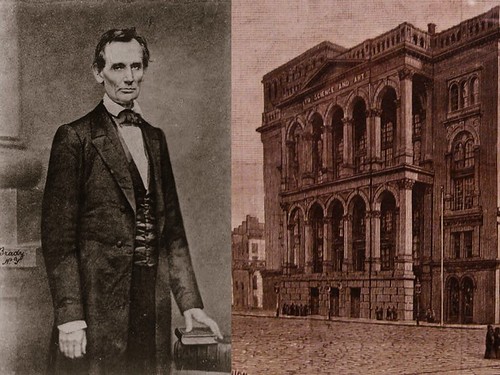

Abraham Lincoln, in a portrait by Matthew Brady taken only hours before his famous Cooper Union address, given 151 years ago last week. Insert: a contemporary view of Cooper Union, from an engraving in Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 1883.

Abraham Lincoln, in a portrait by Matthew Brady taken only hours before his famous Cooper Union address, given 151 years ago last week. Insert: a contemporary view of Cooper Union, from an engraving in Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 1883.It’s a common trope around these parts, and a friend of mine says it all the time. “Huh? What? I mean, come on, I don’t know about that.” It’s almost palpable as you cross from Broadway west to east, this game of contention.

Socially, politically, it’s been a longstanding history, going back to the 1850’s, when the urbanity of lower Manhattan began to seep like an aroma into the enclave we now call “The East Village.” But more than that, it was almost as if a lens had been held up to catch the lunar rays, and send them down here, right here, a place like nowhere else, where skeptics and firebrands, bohemians and bon vivants converge to strike their poses. One might wonder where all this contention had its start, yet I believe it was never more apparent than when Abraham Lincoln came here to speak.

On Feb. 22, 1860, on the eve of the great Civil War and before his nomination as Presidential candidate seemed possible, Lincoln boarded a train that drew him some 1,800 miles eastward, all six feet five inches of him, folded like a jackknife into a second-class seat. He had a speaking engagement scheduled in New York, and that alone was worth the trip. Originally, he was set to speak in Brooklyn, but a change of venue brought the affair to Cooper Union, a recently established learning center designed to draw thinkers and dreamers to an area that had become, well, just a bit slummy.

Our “Prairie Orator” arrived in New York on Feb. 26, dressed in a brand new suit. It was, however, criss-crossed with razor-sharp creases, having come all the way from Illinois in a very small handbag. He looked grotesque, one man said, as he shambled along, exhausted and rumpled, in the cruelest new shoes known to mankind. Once he had booked a room downtown for the night, he sat up late, refining his speech.

The next afternoon, on his way up to the East Village, he stopped on Bleecker Street to pose for the camera of Matthew Brady. In his portrait we see him nervous and gaunt yet still oddly handsome, his jacket full of hair-raising wrinkles, nothing short of a complete disaster. Yes. Abraham Lincoln. Fashion victim.

The Great Hall at Cooper Union that evening quickly filled to capacity with skeptics and dreamers and bohemians galore. They had never seen a guy so homely, and were rudely shocked at his backwoods manner. But they lent an ear to what he said, and why not? They had all paid 25 cents for the honor.

Cool and easy, with his long poker face, Abraham Lincoln stated his case. His arch-nemesis, the racist senator Stephan A. Douglas, had lately implied that slavery was protected by the almighty Constitution. Lincoln, an abolitionist at heart, could hardly wait to contend this. He had truly had his fill of this puffed up wind-bag, and now he had his chance at last: at Cooper Union he would take him down.

Little by little, though his rhetorical gifts, Abe fashioned a straw dummy of Douglas, which he sat on his knee and filled with the senator’s own ill-chosen words. The audience soon caught on to his sly little trick, applauded and laughed aloud. Then Lincoln had his own Tina Fey moment, when he impersonated Douglas and mocked the way he extolled that “gur-reat purrr-rinciple” by which one man can enslave another.

The hall doubled with laughter, and so Abe kept on playing rope-a-dope with his straw-man opponent. And for the breathtaking finale, after the hilarious comic relief, he drew the crowd forward, as if they were one, to confront the looming crisis at hand: disunion, and the threat of civil war. He pointed a finger at the militant slavers and called their bluff in a clear-eyed warning: “Right makes might,” he said.

By the end, Abe had the audience in the palm of his hand. Thereafter, into the night they all fanned out: all the various contrary souls, to seed a new and very contentious quarter in the City of New York, or so my theory holds.

As for Lincoln, he returned alone to his melancholy room. Could he have known that his words would make him President? That they would turn around the very fate of the nation? On that same note, might we in the East Village recognize that it was here, right here, that America’s crisis was first made apparent, where the old world split and then fell away?

Uh oh. Here comes my friend.

“Huh? What? I mean, come on, I don’t know about that …”