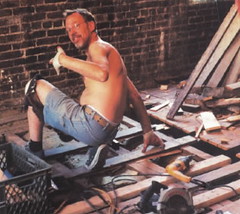

Michael Shenker, a homesteader and long-time community activist in the East Village, died Saturday of liver failure at the age of 54. NYU Journalism’s Dyan Neary, a friend of Mr. Shenker’s, prepared this first-person recollection of his life and the morning of his death.

I wake with a start at 7:25 a.m., sucking air through my lips with a slow whistle and blowing it out again. Nikita is waving at me from her crib. I feel reinvigorated somehow.

It is 7:25 a.m. and I want to apologize to everyone I have ever harmed, even in the smallest of ways. I write an e-mail to Brian, a masterful exercise in humility and accountability. For being a stress case and for being difficult when I was pregnant. I read several books to my daughter.

At 10:30 I gently unroll the down comforter to reveal Brian’s sleeping face. Out the window, I can see so much of the skyline, buildings stacked upon buildings and the Empire State climbing higher than all of them now, the centerpiece to a misshapen staircase like a three-dimensional collage of various shades of tawny overlapping tan.

I’m going to see Michael in the hospital, I tell Brian. Nikita has been changed, fed, read to. I place a kiss on his forehead. Check your e-mail.

There is nothing quite like autumn in New York City. The light of the sun seems to touch down everywhere at all hours of the day, though the star itself is nowhere to be found. It is a tattoo in a concealed location of the body. You might need a mirror to see it, but you know it’s there.

I walk through the main entrance of Beth Israel Medical Center and approach the front desk. The young, bald black man behind it wears a smart blue suit and a kind smile. I am grateful for the simple gesture.

Excuse me, I’m looking for the Karpas unit.

What floor?

Fourth.

Go all the way down this hall and make a right. Take the elevator to the fourth floor and follow the signs.

It seems so easy. As I walk down the hall, speed-walking so that I skip a little, it might seem to a passerby that I have something to celebrate. We are all hoping for the best, but that would certainly be pushing it.

He was admitted just last night. I had gone to his apartment and missed him by an hour. He was in a lot of pain, Liz had said, so he’s having a procedure done on Monday and he’ll be home Tuesday.

At the elevator I feel better already about all this. I am getting closer. In one minute I will see Michael. And maybe this won’t even be good-bye, maybe it won’t be two weeks, maybe he’ll look better than he did the other day.

I remember our walking tours of the Lower East Side, when Michael and I would meet a couple times a week, grab dinner at Angelica’s on East 12th Street and roam the area. I was filming a documentary in various U.S. cities, and Michael had volunteered to be my main New York City subject.

It was Brad, a great mutual friend of ours, (and a former long-term boyfriend of mine), who suggested that I begin shooting the documentary. We had talked about it when I was in New Orleans after Katrina. He and Michael had left messages on my voice mail, passing the phone back and forth. Hurricane Rita had just hit, and they wanted to make sure I was alive. It was nice to know they were together and it made me a little homesick in another crazy city far from my own.

When I got back to New York and interviewed Michael, he took me all around the Village. He pointed out all the stoops and shops he had frequented throughout the ‘60s that aren’t there anymore, the punk rock clubs and social centers that aren’t there anymore, the apartment buildings and squats and the N.A. meeting on St. Mark’s that isn’t there anymore.

One night when I arrived at his apartment, he rushed excitedly to the piano bench. I wrote a song for you! he’d said. I want you to film it. It’s called Diana—I know your name is Dyan, but I needed the extra syllable.

When Brad was killed by the government of Oaxaca at the end of 2006, Michael picked me up from the airport when I arrived back in New York the next day, crumpled with grief. He made me pancake breakfasts the mornings after I cried myself to sleep on his couch. I am obviously not as close to Michael as some. I regret having barely seen him in the past year. But I’ve known him for a decade, and he is one of those wonderfully unique people in my world.

On the fourth floor, the walls are beige, the ceiling is beige, the floor is some kind of flat tile. My sister would know exactly what all these generic hospital floors are made of. She worked at Verrazano Tile in Staten Island for years, and loves to point out the cost of every terrazzo and textile we come across.

All of the doors are open, so I can peek directly into the private lives of the dying and the people who love them. A woman’s rear end facing the doorway with her maroon pants falling down a little, two ancient women strapped to beds with plastic medical tubes connecting arteries and airspaces to various machines, a man walking around his room with a walker. See, I tell myself, some of these people aren’t doing so bad.

Even the desk at the end of the never-ending hall is beige, and as I approach I am anxious to see my friend.

I’m here to see Michael Shenker, I tell the two young men.

Ohhh, one says, standing up. Hold on, I’ll see if he’s still here. They must have moved him to another floor. I watch him walk to where a corpulent, frizzy-haired nurse is standing outside one of the rooms.

They talk for a while. I can almost stretch those moments into minutes like a wad of chewing gum. There is whispering and nodding and shrugging and my eyes wander uncomfortably around the room. Beige corners, peeling paint, wonder if anyone else has noticed that, hope it’s not lead, beige eyeballs, beige around the edges of the world of my life of the longest moment that has ever been. A pile of files on top of the desk and one creamy manila folder, black words on beige staring up at me, right on top for all to see:

Michael Shenker

Expired

I walk to where the two are standing, outside what I know is his room.

What’s going on?

I’m sorry… the patient was just brought upstairs to the morgue, says the man.

You missed him by 10 minutes, interjects the frizzy woman as though she has to defend herself. We didn’t realize anyone else would be coming.

Oh. I nod slowly. They think I knew he had died. They think I came to visit with his body.

What were you to the patient?

Friend. My mouth is very dry. There were people here?

Yes. His son.

I know he didn’t have a son, but I’m sure it was Rob, our friend and Michael’s health proxy.

What… time?

The frizzy nurse looks at something on the wall. 7:25 a.m., she tells me.