Earlier this week, the Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute launched “Blowing Minds: The East Village Other, the Rise of Underground Comix and the Alternative Press, 1965-72,” with a rousing discussion that’s now archived on the exhibit’s Website, along with new audio interviews with veterans of the Other. Over the course of seven weekend editions of The Local, we’ve heard from all but one of the EVO alumni who spoke on Tuesday’s panel. Here now, to cap off our special series, is the story of Peter Leggieri.

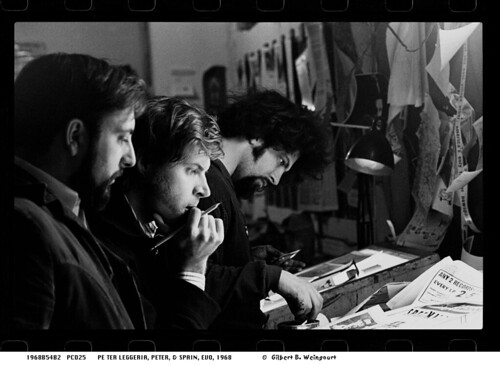

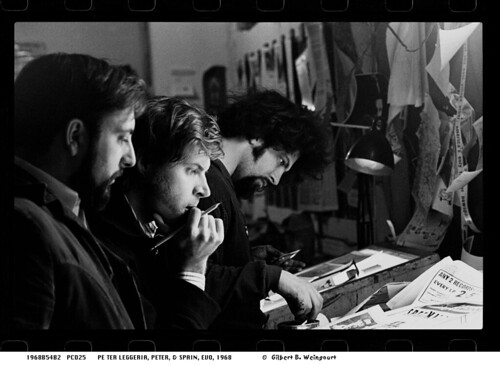

Gil Weingourt Left to right: Peter Leggieri, Peter Mikalajunas, and Spain Rodriguez.

Gil Weingourt Left to right: Peter Leggieri, Peter Mikalajunas, and Spain Rodriguez.From the first day that I began working at The East Village Other, I was overcome by the sense that it was not only a newspaper but a strange and magical ship on a voyage with destiny. It seemed as though each issue printed was a new port of call, and the trip from one issue to the next, a new adventure. Many of EVO’s crew members expressed that same weird feeling – a sense of excitement and creative power.

And what a crew that was! No one was recruited. I don’t recall a resume ever being submitted. They all simply showed up and started working. EVO’s crew might just have been the greatest walk-on, pick-up team in the history of journalism. She was The Other but her staff of artists, poets, writers, photographers and musicians affectionately called her EVO. Her masthead bore a Mona Lisa eye. EVO created a cultural revolution and won the hearts and minds of a generation. She was the fastest ship in the Gutenberg Galaxy.

In the Beginning

I was the anonymous Other, the one editor-owner unknown to the public. I did not party. I did not schmooze with the literati or seek publicity. I had no time for such things. I worked seven days a week, 20 hours a day and, because of law school, I had to be sober. My friend, the poet John Godfrey, told me that I was afflicted with a Zen curse: a hermit condemned to be surrounded by people and events. That was certainly the case for me in the 1960s. Read more…

Because something is happening here

And you don’t know what it is

Do you, Mister Jones?

– “Ballad of a Thin Man” by Bob Dylan (from “Highway 61 Revisited,” 1965)

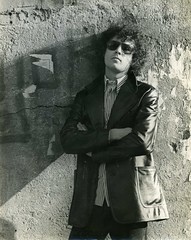

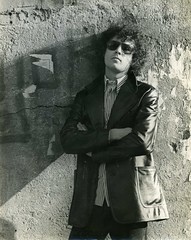

Alan Abramson, 1972.

Alan Abramson, 1972.The times were overwhelming. America was violently awakened from the slumber of the 1950s on Nov. 22, 1963 and quickly found itself inhabiting an unrecognizable, incomprehensible, rapidly evolving reality. The Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, the Free Love Movement, the Women’s Liberation Movement, the Gender Equality Movement, the Consciousness Raising Movement, the Save Our Planet Movement, the Eastern Mysticism Movement, and sex, drugs and rock and roll all conspired to create a giddy, euphoric Renaissance. If you were a nice young person raised in Eisenhower-era suburbia, the questions that consumed you were: “What the hell is going on? What does this all mean? Where do I fit in?” And most importantly: “How do I get invited to the party?”

Enter, The East Village Other. For me it was the Rosetta Stone that enabled me to decode the meaning of the ‘60s. Attending Oberlin College from 1964 to 1968, I experienced an environment that was receptive to the Strange Days that were sweeping the nation. I had a subscription to the Village Voice, which retained an aura of cool, post-Beat sensibility.

All of the sudden, however, it was left way, far behind: things were happening much too quickly for it to process. The ‘60s were not about quiet, low key cool. The ‘60s were flaming hot. There was a void in the media. Nature abhors a vacuum and something Other was desperately needed (I always felt that the name was a play on words, dissing its neighbor from the West Village). Like Athena springing fully clad in armor from the aching head of Zeus, The East Village Other burst upon the scene. The Other was not your parents’ newspaper. Read more…

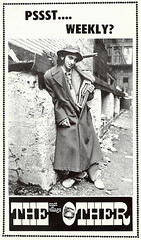

Nancy Naglin Joe Kane

Nancy Naglin Joe KaneA veteran of The New York Ace, High Times, The New York Daily News and many other publications, Joe Kane describes how he got his start at EVO.

When I first migrated to Manhattan from Queens in 1970, it was with dreams of becoming a working scribe, preferably writing Beat fiction (unfortunately, one of the few things I was born too late for) and/or covering film in some capacity. Instead, I landed a boring temp job typing at a downtown insurance firm. During this time, somewhat happier circumstances led me to Screw, where the magazine’s then-art directors, Larry Brill and Les Waldstein, were going halves with publisher Al Goldstein on a new spin-off tab titled Screw X, a satirical variation on Screw (the height of redundancy, no?)

I auditioned for a writing/editing gig, with no guarantee Larry and Les would even get back to me. But a couple of days later, the phone rang in my East Sixth Street pad with promising news from the pair: Seems my work had been extolled by another of their writers, Dean Latimer, who told them it was “almost as good” (accent on almost) as his own stuff and that they should hire me straightaway.

For me, this was a frankly stunning turn of events. It so happened that Dean, whom I had never met, was already something of a personal hero; his “Decomposition” column and other writings were my favorite sections of The East Village Other. I considered Dean one of the most vivid and versatile writers I’d ever read anywhere, one equally adept at reportage, “think pieces,” memoir, criticism and totally devastating satire. That he had encouraging words for my fledgling efforts cheered me no end, and I resolved to thank my benefactor for his unsolicited largesse. Read more…

Deanne Stillman Rex Weiner, circa 1971.

Deanne Stillman Rex Weiner, circa 1971.Rex Weiner co-founded The East Village Other’s successor, the pioneering New York Ace (1972–73) and according to his FBI file, was a founding staff member of High Times. He recalls getting his start at EVO.

My first week aboard The East Village Other, its venerable editor-in chief Jaakov Kohn squinted at the name I’d signed to an article, clutched his blue pencil spasmodically, and curled his whiskered lips in disdain. In an Eastern European accent nearly as impenetrable as the cloud of unfiltered Lucky Strike smoke curling from the butt in his nicotine-stained fingers, he declared, “You look more like a Rex to me!”

The newly minted moniker echoed amongst my new colleagues in the vast, shadowy loft. At EVO you had the name you were born with and the name that EVO gave you: Jackie Diamond was Coca Crystal, Alan Shenker was Yossarian, Jackie Friedrich was Roxy Bijou, Jaakov was “The Arab,” Charlie Frick was Zod, and so on. And so with my next byline I was reborn in 1970, a new decade with a new name, and on my way as a writer, of sorts.

I’d walked out of the clanking elevator into the EVO office that fall, a 20-year-old N.Y.U. dropout from upstate and a Lower East Side inhabitant since I was 17. Two of my closest friends from high school were lost, one to Vietnam and the other to heroin, allowing me to nurse a tragic heart tinged with righteous political outrage. With half a dozen porn novels credited to my name — or pseudonym — for a Mafia publisher, and a handful of poems I’d recited at St. Marks in the Bowery, I thought of myself as an established writer. I appointed myself EVO theater critic, filling a staff vacancy, and felt right at home. Read more…

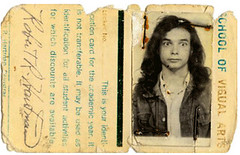

EVO poster showing Mr. Frick.

EVO poster showing Mr. Frick.Charlie Frick was a rock n’ roll writer and photographer for The East Village Other. He was a network television cameraman and in more recent years has become an independent media consultant. An original light box is among the artifacts he rescued from EVO’s last office in the Law Commune at 640 Broadway. Writing in 1979 for an Alternative Media Syndicate publication (hence at least one instance of “alternative” language), he described the “controlled artistic anarchy” of psychedelic design.

Tripping the Lightbox Fantastic

For more on “Blowing Minds: The East Village Other, the Rise of Underground Comix and the Alternative Press, 1965-72,” read about the exhibition here, and read more from EVO’s editors, writers, artists, and associates here.

Robert Hughes once described the weekly paste-up night at The East Village Other as “a Dada experience.” The year was 1970 and while none of us who were toiling into the wee hours of the morning at one of America’s oldest underground papers (founded in 1965) knew what he was talking about, we nevertheless assumed that to get Time’s then newly appointed art critic to spend some of his first weeknights in America with us, we were doing something weird and perhaps even important. “Dada was the German anti-art political-art movement of the 1920s,” he explained in his cool Australian accent. “And this is the closest thing I’ve come to seeing it recreated today. I’m really grateful for the chance to be here.”

Yet he needn’t have been so grateful. He was as welcome as any other artist, writer, musician, hanger-on and at that moment, detective Frank Serpico, the most famous whistle-blowing cop in America, was stationed at the local Ninth Precinct and would came around periodically in his various undercover costumes to schmooze with the EVO staffers. Paste-up night was open to anybody who drifted up to the dark loft above Bill Graham’s Fillmore East, a former Loews Theater turned rock palace on Second Avenue and Sixth Street, just next door to Ratner’s famous dairy restaurant, in a neighborhood that in the Thirties was the heart of New York’s Yiddish Theater. At that time it was the East Coast hippie capital.

Beginning at seven or eight o’clock at night and lasting until dawn, the regular and transient layout staff took the jumble of counterculture journalism and anti-establishment diatribe that was the paper’s editorial meat and threw it helter skelter onto layouts that were pretty anarchic. Anyone could join in whether they had graphic design experience or not, yet many of the gadfly layout artists were too stoned to complete their pages which were finished on the long subway ride to the printer deep inside Brooklyn. Read more…