Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images From left: Dan Rattiner, Walter Bowart, and brothers Allen and Don Katzman. Jan. 14, 1966.

Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images From left: Dan Rattiner, Walter Bowart, and brothers Allen and Don Katzman. Jan. 14, 1966.Little is it known that Dan Rattiner, doyen of Dan’s Papers, helped launch the East Village Other alongside its more celebrated founders, the late Walter Bowart and the late Allen Katzman. In 1964, having abandoned graduate school in architecture at Harvard, Mr. Rattiner, in between gigs producing a summer newspaper in Montauk, rented an apartment in a brownstone on West 10th Street in Greenwich Village. A year later, in the fall of 1965, something amazed him on the newsstand at Eighth Street and Sixth Avenue. He picks up the story from there.

It cost 15 cents and was an enormous piece of newsprint all folded up into tabloid size. The four pages, when unfolded looked more like a work of modern art than a newspaper. A new way to print a newspaper was on the market. It involved using scissors and rubber cement to put together a proof of a page, then making a plate from a photograph of it and then printing from that. But I had never seen anyone make use of the new process like this before; most people just used it to mimic the old.

As for the content, it was also revolutionary. The lead headline read: “TO COMMEMORATE THE GLORIOUS NEWSPAPER STRIKE THE HERETOFORE UNDERGROUND ‘OTHER’ EXPANDS ITS PATAREALISM.” In huge black type, the words coiled along the perimeter of the page and ended with a half-tone photograph of a half-closed eye. “Peace Rally Breeds Strange Bedfellows,” was the headline below. “Generation of Draft Dodgers” read another headline below that.

I bought it. And I looked for, and found the name, address and phone number of the publisher and editor, Walter Bowart.

I called him right then and there, from a pay phone on the corner. He answered the phone. “This is an amazing newspaper,” I said. “Do you plan to do a second one?”

“I have no idea,” he said.

I told him I had published newspapers in the Hamptons and Montauk, and had the winter to myself. I told him he could make a go of it if he wanted to and I could help him. It needed ads, for one thing. Otherwise, it was terrific. He invited me over.

I walked to a loft on the fourth floor of a tenement at Avenue B and Second Street, passing through this very filthy, very run-down and partially abandoned neighborhood I knew as the Lower East Side, but which recently had been renamed The East Village by some enterprising artists. I passed dope addicts, drunks lying in the gutter, students, trash, immigrants, policemen. I saw, on one corner, a policeman smoking what I was sure was a stick of marijuana. It was a bad place.

It had taken me twenty minutes to get over there. Then there was the climb up the stairs, and at the door was Walter — in a bathrobe, smoking a joint. He was a slender man with black hair, a mustache and a long nose. He had a stern gaze.

The apartment was a painter’s studio. Huge canvasses hung everywhere and more were lined up in racks along the wall. One of them, about six feet by ten feet, was an oil painting of a pig. Another was a kind of collage of objects. Scattered about were paint buckets and brushes, ladders, tubes of paint, easels. A girlfriend who Walter introduced to me as Sherry [Needham] eyed me warily and went away. Walter offered me a joint, which I took a drag on and promptly had a coughing fit. Then we sat down.

Walter, I learned, had been born and raised in Oklahoma. He went to college there, had become a painter, dropped out, and then moved to New York to be part of the art scene. We were almost exactly the same age. I told him about the newspaper I published and what I thought of his paper.

“I’ve never seen anything like it. Where did you come up with this idea, attaching all the pages, publishing stories sideways and upside down?”

“Thought of it,” he said.

“Is there any other newspaper in the East Village?” I asked.

“No.”

“Well, you have an opportunity here. This is a new community. This could be a counterpoint to the Village Voice. A new Village Voice.”

“Wow.”

“And I could do it,” I said.

We traded philosophy. I talked about writing profiles of some of the more prominent artists of the area, writing editorials protesting the Vietnam War, pointing out nasty landlords, writing stories about shops and restaurants, giving space to new ideas and new ways of doing things.

“It needs to be weekly,” I said. “To compete. There’s a lot of advertising out there.”

Walter put on a Bob Dylan record that played “Ballad of a Thin Man” and he told me his philosophy. Radicalism. Anarchy. Legalize Marijuana. Free love, free drugs, free press. End the War in Vietnam.

“People don’t know what’s going on. It’s right here in the East Village. Listen to the song, man.”

“Sounds good to me,” I said.

Within an hour, we decided we would go into business together as partners. Fifty-fifty. I went home. But the next day, we met again and he talked about each of us putting up $500 and a third person.

“He’s a poet named Allen Katzman,” Walter said. “He doesn’t know anything about newspapers and he won’t be around much. But he’s a friend of mine. He’s going to be a third partner.”

“Why don’t I get a friend as a fourth partner?” I said.

“Look. I founded the paper. What if we don’t agree? Allen would vote with me probably. So that would decide.”

I couldn’t argue with that.

Within a few days, we were incorporated. Stock was issued. Probably the most anti-establishment, counterculture newspaper ever created was put together as if it were from Wall Street. I met Allen Katzman, who was nice enough. And apparently, he had a twin brother who was an accountant. He incorporated the newspaper as a company and issued nine shares. I put my three in a safe deposit box at a bank.

The second issue of the East Village Other, cut, glued and assembled in Walter’s loft, appeared in early November 1965. It was still done as a collage, but now it was a regular tabloid newspaper, eight pages long. I had brought my jeep in from Montauk – I could keep it in town until April when I’d have to go back to Montauk – and Walter, Allen and I drove around to newspaper stands and delivered it. Sold it for fifteen cents. We got seven and a half. Nobody turned it down.

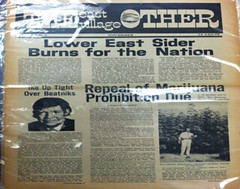

“Lower East Side Burns for the Nation” was the lead story, about a guy who burned his draft card. “Ike Uptight Over Beatniks,” was another, as was “Repeal of Marijuana Prohibition Due.” I also wrote. “Our Slums: 148 Avenue C: No Heat and a Child with Pneumonia,” was my story for issue No. 4 in January 1966. We were underway.

Just before the third issue, Walter called me at the apartment on West 10th Street.

“Meet me at the office,” he said.

“What office?”

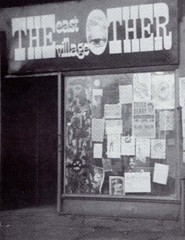

It was a storefront on Avenue A between Ninth and Tenth Streets facing Tompkins Square Park, which at the time was a useless, overgrown tangle of concrete and dirt that had a band shell at one end, sprouting weeds. I went inside.

“This is wonderful,” I said.

Walter, wearing a tool belt, was holding a hammer. He was building a counter at the front, new stud walls and a window seat. There was fresh lumber leaning against the wall.

“The sign comes tomorrow,” he said. He pointed above the show window. “EAST VILLAGE OTHER.”

By the end of the next day, we had tables, chairs and desk and lamps, and we were moving in. Above the front door, the big sign featured a half-asleep eye inside the letter O in Other. Stoned, we were.

But not me. I was the “straight man,” as people said. I came, every morning, on the cross-town Eighth Street bus from the cool, beat world of Greenwich Village on the West Side to the mean, filthy streets of the wild-eyed East Village. I got off at St. Marks Place and Avenue A. And I walked up a block and a half. I had a job. No pay; but a job.

As for Walter, he didn’t get paid either. He worked in bars, such as Slugs, and if I went there, he’d grin and slip me a free drink.

Walter brought in maniacs to answer the phone and type up stories. People with beards and rumpled clothes. Other people with capes and headbands. I hired salesmen in regular clothes and trained them by walking with them down St. Marks Place to sell space in the paper to bead shops, hip clothing stores and art supply houses. A disco called The Electric Circus was opening up. I sold it an ad.

Walter spent half his time getting stoned and half the time going to rallies, writing diatribes and yelling at people to get things done. I wrote editorials against the war and articles about a nude commune. I also arranged for a professional delivery company to handle the distribution. There were two of them. Word on the street was they were Mafia-controlled but I didn’t care. We needed them. I invited them to come by and we negotiated a deal.

EVO thrived, or seemed to. By January it was weekly. It was also supporting more pages and growing. It was a hit.

Since Walter was the main partner, he had the checkbook, which he had given to his girlfriend Sherry and she handled the bills. I trusted her. And now there was money coming in. People writing checks to us for ads. We were even getting a hundred dollars and more a week in distribution money, which came as cash, from the distributor. It looked like some day we might even make a profit.

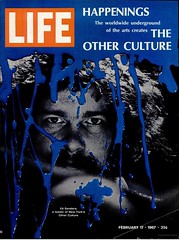

Soon there were drawings and articles in the paper from R. Crumb; from Tuli Kupferberg, who wrote the most outrageous, hilarious, and embarrassingly scatological articles; from Jaakov Kohn, from Abbie Hoffman. I met them all. And there was Ed Sanders, the head of the Peace Eye Bookstore, down the street. In February 1967, the cover of “Life,” the country’s largest circulating magazine, bore his image.

“We’re hippies,” Walter said when he saw it. “We weren’t hippies when this started, man. But we are now.” We would let our hair grow long. We would fit in.

For more on “Blowing Minds: The East Village Other, the Rise of Underground Comix and the Alternative Press, 1965-72,” read about the exhibition here, and read more from EVO’s editors, writers, artists, and associates here.

This post has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: January 22, 2012

Because of an editing error, an earlier version of this post misstated the year of EVO’s first issues. It was 1965, not 1966.