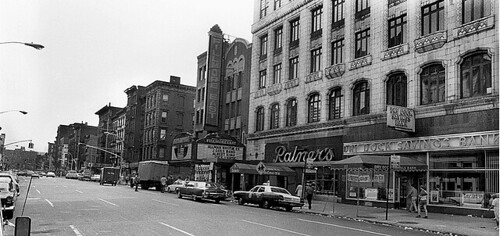

Amalie R. Rothschild A huge crowd formed around the Fillmore East in May 1970 when tickets went on sale for Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young.

Amalie R. Rothschild A huge crowd formed around the Fillmore East in May 1970 when tickets went on sale for Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young.The push to preserve blocks of the neighborhood through a landmark district has, not surprisingly, led to a lot of conversations about the history of the area. The proposed district covers roughly six blocks, and perhaps no property within the tract has hosted more important figures in American culture than the former Fillmore East building at 105 Second Avenue.

Now, the entrance to the building is an Emigrant Savings Bank, and the 2,600-seat theater has been replaced with an apartment building. But the Fillmore’s three-year existence had a lasting impact culturally; Jimi Hendrix, Joe Cocker and Miles Davis all recorded well-regarded live albums there. The Who played their rock opera, “Tommy” in its entirety for the first time in the United States in 1969 at the Fillmore East. And the first rock concert to be broadcast on television was taped there in 1970.

But the Fillmore’s impact went beyond the performers onstage. Numerous technological innovations during the theater’s short existence were adopted at concert venues across the country.

“I was blown away by what a creative, experimental theater environment there was at the Fillmore East,” said Amalie R. Rothschild, a photographer who was among the many NYU students who landed dream jobs at the Fillmore when it opened in 1968. “It was a real place to do real things. The students had a live laboratory within which to work.”

The man behind that environment was Bill Graham, the rock promoter who first made a name for himself with the Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco. After his success on the West Coast hosting some of rock’s biggest names, Graham returned to his native New York to open another venue.

He purchased the building near Sixth Street, which had previously been a music venue, a Loews cinema, and a Yiddish theater. Within the first year Graham had booked the likes of Janis Joplin, the Who, and Jimi Hendrix.

“It was the top of the heap, guys were just jazzed to be there,” said Jerry Pompili, the house manager of the Fillmore East for most of the time it was open.

With its top-notch sound system, elaborate psychedelic light shows that accompanied performances, noble, theater-like environment and first class treatment of musicians, Graham’s East Village Xanadu attempted to elevate rock music from mere spectacle to art.

“Bill had hit on it. He gave us dignity,” Pete Townshend of the Who said in “Bill Graham Presents,” an oral history of the rock promoter’s life. “We were dignified people. We were artists.”

But that atmosphere that so attracted the Allman Brothers, the Grateful Dead — and on one occasion John Lennon and Yoko Ono for an impromptu 2 a.m. performance following a show by Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention — proved unsustainable in the face of arena rock.

“The business began to transform from coffee houses and theater venues to Madison Square Garden and stadiums,” said Ms. Rothschild, author of “Live at the Fillmore East: A Photographic Memoir.” “Woodstock made it clear that hundreds of thousands of people would come out for this type of music.”

On June 27, 1971 the Fillmore East closed. Of course, there was a heck of a show featuring a lineup that would make the most jaded of music buffs drool: the Allman Brothers, the Beach Boys, Albert King, the J. Geils Band and others.

“The concert went until 6 a.m.,” Rothschild recalled. “Nobody wanted it to end.”