Photos: Daniel Maurer

At Bagel Café and Ray’s Pizza, on the corner of St. Marks Place and Third Avenue, a mural depicts nearly 25 scenes of the East Village. One panel features Telly Salavas in front of the Ninth Precinct stationhouse. Another depicts Deanna’s, a popular early-90s jazz club on East Seventh Street that catered to bebop lovers on a budget. The largest of them, running across the entire back wall, is an East Village cityscape watched over by the World Trade Center’s twin towers.

And then there’s the one that includes a tranquil scene in Tompkins Square Park, also in the early 90s, when the park was shedding its scars from the riots. The signature at the bottom right of the panel reads: H Platschka. Next to the autograph, strangely enough, is a phone number.

Call that number and Hermann Platschka will pick up. He calls himself Hermann the German. The artist, “76-years young,” recently accepted The Local’s invitation to tell the story of the murals. Thickset, with a short-cropped beard, he arrived at the Bagel Cafe clad entirely in black, from his shoes to his beret to his black leather jacket to his black-framed glasses.

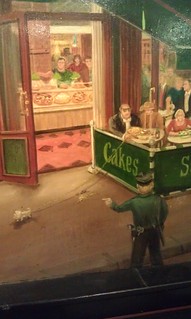

His tour started with the first panel he painted, of Gem Spa. “The East Village was a dangerous place then,” he said, pointing to a fair-haired night watchman standing outside the candy store: “The ladies’ favorite, a cop with movie-star looks. It was dicey then, and he was the law.”

Mr. Platschka moved to a wall depicting a loving trompe l’oeil rendering of McSorley’s bar. “That is my favorite. The best execution.” Then he ran his finger along the wall toward the next mural, the street view of Bagel Café with the Astor Place cube in the foreground. “Look, the buses are exactly as they were in 1994,” he said. “This one has ads for Greek Village, a restaurant owned by the same people [as Bagel Cafe]. I gave them more signage.” Of his painting of the Peter Cooper monument, he said, “I remember wanting to give some history and that statue looked nice and historical. He is sitting in a chair like Lincoln, which made it look important.”

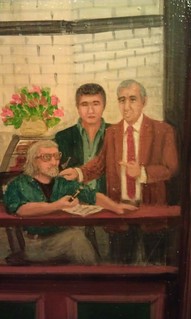

The final panel is the Bagel Café itself. The grey-haired man in a beige suit and red tie is the original owner of the cafe, Louis Pappas. “He’s mostly in Florida now,” Mr. Platschka said. “That’s his son, Paul Pappas.” He pointed to a young 20-something standing next to Louis in a casual jacket over a light green shirt open at the neck.

The artist tapped a calloused finger against a bohemian man of around 50, seated at an outside table in a dark green shirt, with long salt-and-pepper hair and funky glasses, holding a black art marker to a sheet of paper. “Me!”

Hermann the German was born in 1936 in Dorfen, a small town near Munich, and grew up during World War II. After graduating from school in 1950 and working as a window dresser and eventually a head decorator at a department store, he decided to start his own business making floats for Germany’s wild Carnivals. Soon breweries, cheese factories, and even a steel factory were asking him to create displays.

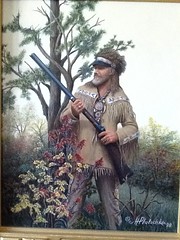

In 1985, his biggest client, Atomic Ski, asked him to create a company booth for a Las Vegas sports trade show; Olympic downhill skier Bill Johnson was to be the exhibit’s star. That’s when Mr. Platschka first flew to America and set foot in New York City. “I bought a conversion van to go across the country by myself to Salt Lake City, where Atomic Ski West was located.” He traveled wherever Mr. Johnson went, at one point stopping in Cheyenne, Wyoming where his sister was married to an Air Force man. “Right beyond their garden began the big prairie Karl May wrote about in one of his western novels,” he said. “You know Karl May? He was huge in Germany; he was Albert Einstein’s favorite novelist. When I faced the prairie, I knew I had to stay. The great American West took total hold over me.”

Mr. Platschka smiled broadly. “Art, if you live the life, will take you places.”

So he left Atomic and befriended two Wild West originals, Timberjack Joe and Ridge Durand, modern-day trappers who partly inspired the Robert Redford period movie “Jeremiah Jones.”

“The three of us went to rodeos, Indian festivals, all over Wyoming, Colorado, Utah and South Dakota,” Mr. Platschka said. “I felt like a real man of the Karl May west. They taught me to find gold in Colorado rivers, to watch how beavers build dams. But eventually I knew this beautiful part of my life would not last forever either, and I had to go back east to Germany.”

Back in New York, while trying unsuccessfully to sell his van, he stopped for a slice of pizza on Seventh Avenue. He struck up a conversation with Rosolino Magnaro, a Sicilian pizza legend who owned almost 20 locations of Famous Original Ray’s. “In my van he saw a model I made for a hotel chain, Swiss Chalet,” Mr. Platschka recalled. “He told me he was looking for a person to design a big store he was opening two blocks further down on Seventh. I made some designs for him in my van studio. He loved my work. I was newly divorced, and I had opportunity. I knew right that second that I’d be staying in this great city for the rest of my life.”

And so, like Michelangelo and Donatello and so many others before him, Mr. Platschka found a prominent Italian patron to support his art. Famous Original Ray’s was everywhere, and Rosolino “Ray” Magnaro had money for murals and interior design.

Mr. Platschka loved the easy feeling of being his own man, but after his travels, he didn’t have enough cash to rent a place of his own in the city. But he didn’t want Ray Magnaro to know that it wasn’t just his belongings – cameras, artist tools, paintings – that resided in the van. He made up paltry excuses, shaving and giving himself birdbaths every night at the city’s best hotels to keep up a professional appearance.

“Maybe Ray figured it out, because one day he said, ‘Listen, if you are interested I have some office space for you.’ Shortly after, he gave me a little house on Amsterdam and 82nd Street, next to a church and close to his business where I could work and live,” Mr. Platschka said. “After three years, Ray needed the house for his own business and I moved to West 86th Street in a three-room apartment on the ground floor. I paid my rent by skill: I did a ton of work to improve this old-fashioned building, still called Dexter House, and meanwhile, I painted more murals and redesigned the famous logo for Famous Original Ray’s.”

In 1986, a former worker at Ray’s formed the now omnipresent Famous Famiglia’s with his Albanian brothers. They hired Mr. Platschka, at a higher rate, to paint murals of Venice as well as portraits of famous Italians like Rocky Marciano and Frank Sinatra. Year after year, he was able to pay his rent by exploiting this pizza-parlor niche overlooked by other artists.

Meanwhile the United Nations, in an effort to help illegal immigrants, asked the artist to form a soccer league for people from the pizza community. “I coached over on Sixth Street and FDR Drive, the field near the track,” he recalled. “There was a blond woman named Polly who kept running at the same time as our games, a marathon runner, very good. She later admitted she timed her practice to when I came. She asked and I agreed to meet her. But that day the UN called me to take the game to a field in Queens. I had no number for Polly, so I told our assistant coach to take the game instead while I stayed behind. Now I’m married to Polly 15 years.”

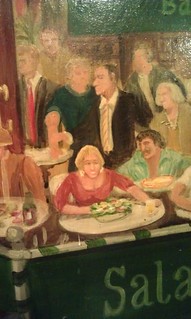

In the mural at Bagel Cafe, Polly is eating a Greek salad at a sidewalk table, in a red dress with silver drop earrings.

Mr. Platschka moved in with Polly to the Village View Mitchell-Lama complex near Avenue A. The mural of the trade towers was designed from a sketch he made from the 19th-floor balcony of the apartment he still shares with her there.

At that time, around 1990, Mr. Platschka met the man who has been his benefactor ever since. Louis Pappas was then building up a mini-empire along St. Marks Place. “I moved from Italian patrons to the Albanians pretending to be Italian, to the Greeks. Since a Greek man was now paying me, I thought now I should paint someone Greek. In Bavaria, my favorite show was Kojak, and the show was filmed right near here in the Ninth Precinct house on Fifth Street. So I snuck a portrait of Telly Savalas into one of the Bagel Café murals. Louis Pappas loved it.”

Mr. Platschka painted the murals during a brief period when the slice joint was called Bagel Café and Pizza Lovers. Paul Pappas, the son of Louis, later explained to The Local that they were then experimenting with a Boston-style pizza, baked in a pan. “That died immediately,” he admitted. “Dad slapped ‘Ray’s’ back on the front of the restaurant, brought back the slice, and business went right back to normal. But Hermann captured that Boston pizza moment.”

“We consider Hermann our artist,” he continued. ”He has done a lot of work for family businesses all over the city, and he even made a Jacuzzi for the living room of my one-bedroom apartment. You got to see it to believe it.”

That’s right, he builds Jacuzzis.

Like Mr. Platschka, Louis Pappas refuses to retire, but he spends most of his time in Florida, leaving his four children to run his holdings. Debbie is general manager of the Chelsea Savoy, and the oldest brother John heads the Park Savoy on West 58th Street. Paul has the Bagel Café; the fourth brother Billy is on duty at St Mark’s Hotel. Billy also oversees the St. Mark’s Ale House, where more of Mr. Platschka’s paintings are on display. One of them, of his hometown brewery, bears the inscription “Hopfen u. Malz. Gott Erhalty” (“May God protect hops and malt”).

At the Ale House, Mr. Platschka said he did more than just paint the walls. “This was a labor of love, a valentine to Bavaria. I did everything,” he said, pointing to the ceiling, the windows, even the dark wooden flooring. “See those communal tables, so trendy now? I think I was first with them in New York. I carved them myself. I designed and built the outside of the Ale House. And the inside: I told them no neon. I wanted it to be like a Bavarian ale house, dark and lively.” He carved the giant wooden bar and created the signature stained-glass windows of medieval monks drinking ale.

“When I redid the design for them, I got offered 10 percent of the bar’s revenue as my payment. And I declined. I was so stupid. A sports bar is a goldmine,” he said. “What did I know? But I got paid, I can’t complain.”

One door down at the St. Mark’s Hotel – once a notorious destination for the drug-addled and prostitutes, now more geared to a hostel culture – John hired Mr. Platschka to create a series of paintings and murals to spruce up the seedy interiors. He responded with several of his beloved dips into history: a scene modeled after a print of the Third Avenue elevated rail in its first years; a vision of the hotel in horse-and-buggy days; and Peter Minuit selling Manhattan to the Native Americans.

“This one is General Grant on his victory ride,” said the artist with a smile. “I just love Grant. He was a great champion of human rights.” Up the stairs, still more treasures line the hallways.

After standing motionless for a short while in front of a pristine 1600s Manhattan harbor scene, Mr. Platschka started to button his coat.

“I have to leave you,” he said, gentlemanly but firm. “I’m working on a painting now, a gift for my wife.”

“You never retire if you’re an artist,” he added. “I’m going to retire when I’m dead.”