William S. Burroughs would’ve turned 99 this month. Portraits of him are currently on display, but Tim Milk, who met the literary lion, thinks they’re not to be believed.

Ask anyone. They’ll tell you. The invisible man cannot be photographed. I should have known better than to try.

“El hombre invisible,” as he was known in Tangier, ever dodgy and evasive, was infamous for his vanishing acts. Whenever he did appear in the flesh it was a set-up, an illusion, the oldest trick in the book. As a matter of fact the entire extant history of William S. Burroughs is a complete fabrication. All those blurry shots from the 1950s — so evocative of the times, boasting the faces of America’s greatest writers — that was also a sham. That fellow standing next to the Beat Poets in Paris or New York isn’t the real Burroughs. He is nothing but a stand-in, an extra in a documentary film — dim, jerky, faraway.

“Now you see me, now you don’t,” said the last of the great Midwestern story-tellers. Never mind that his stories were phrases drawn at random, or not so random as he preferred it, indicating broadly that chance as a concept did not exist any more than he did. By shredding his manuscripts and reading across, inventing incantations from the results there before him, he could mesmerize the whole room and disappear unnoticed.

Poof.

So you were taken in the same as I was. Well, don’t feel too bad about it. Happens to the best of us. The corner of the photograph that escaped everyone’s attention will swallow us all one day, but not “El Hombre Invisible.”

My quest began in February of 1978, on my initial trip to New York. My digs were a cavernous former workhouse directly across from where Burroughs lived at 222 Bowery. One stormy evening found me there all alone, with the sleet coming down thick and relentless. By nightfall the icy slurry was six inches deep: not a night fit for man or beast.

On the windows across the way the blinds were pulled down. Fitful silhouettes of men played across them, producing a startling film-noir effect. They were drinking, smoking, pacing. One of them jabbed at the air with his cigarette, another nursed himself from a rock glass. Sometimes their shadows would whisk away and vanish for a while, only to loom once again into view.

On the turntable I dropped the needle onto a recording of Burroughs reading “The Chief Smiles,” one of a number of readings on vinyl that were at hand at the loft. Dry-as-gin came his voice, floating out into the dank, cold air.

“He is now singing the pictures!”

Just then, much to my horror, something moved out from the shadowed doorways, skulking along at street level. At first I though it was a dying dog, but then I realized it was a man, an amputee, missing both legs. The ragged fellow struggled out from the darkness, propelled only by his arms, and began crossing the Bowery, flat on his belly.

“A thin siren wail breaks from his lips now open to the yellow fangs…”

Like a snail through the icy slush the tattered man left his trail. Hand over hand he came…

“Death! Death! Death!”

Trucks and taxi cabs careened wildly in their efforts to avoid him. Not a hallucination, not a mirage, not a trick on my eyes from the dense falling snow; a nightmare it would be if one were asleep.

“The pictures leap and crackle from his eyes!”

I ran to the phone. Twenty times I pressed the button for Operator. Nothing.

“Death! Death! Death!”

The storm must have taken out the line. All I could hear was the clanking of far-distant wires, and the faint one-way party-line conversation of a drunken woman telling a joke. I hurried back to the window. By this time the man with no legs was gone.

Meanwhile, upon the blinds opposite, the shadow-puppet theater continued. All at once, the silhouette of he who I think to this day was William S. Burroughs, wearing his trademark banker’s fedora, flashed in the window. What a score, I thought to myself. I reached for my camera.

Out of film.

“Wait! — Wait! — Time: a landing field…”

Ever since that day I swore to get Burroughs on film. My chance came in 1980. The Saint Mark’s poet Barbara Barg invited me to back her up on guitar at the “Festival di Poetica” in Rome that summer. The New York entourage which converged there included Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, the Warhol star Jackie Curtis, and none other than “El Hombre Invisible” himself, Burroughs.

“No photos!” he barked at the gathered paparazzi. To make himself clear, he pulled up his collar and turned his face to the wall. “Where can a poor guy get a damn Coca-Cola ’round here?” he groused.

He also refused a place in the group photo. “To hell with that,” I heard him snarl. “Show me to my room!”

On a broad soccer field, in a Fellini-esque landscape, the Italian festival lights were already ablaze. Up to ten thousand people were expected to attend each of the three nights of global poetry. At the dress rehearsal, we were told where to stand and when, checked for sound and so forth. When I had finished I saw the Invisible Man speaking to one of the women who was coordinating the Festival. Once again no camera was ready, so I fearlessly strode up to make a connection.

“Mr. Burroughs,” I said, just as the woman turned away.

“Yes?”

I introduced myself as a visual artist. Dauntless I was, despite all things, for he had now fixed me with a rather cold, reptilian gaze. I tried not to stammer.

“I am creating a series of portraits,” I told him.

“Portraits?” he asked, narrowing his eyes.

“Yes. I use a vintage camera to create an old Hollywood effect.”

He looked away, a far-distant gaze, a horizon far enough to evade me.

“I live in New York. I could look you up there if that would be more convenient,” I offered, rapidly losing my nerve. His chilly scrutiny was nearly unbearable.

In a slow, measured tone cold as steel on slate he replied: “I think you’d better discuss this with my secretary.” He then turned, stepped into the milling crowd and, not surprisingly, vanished from sight.

At first I took that as a rejection. But then maybe it wasn’t a flat-out no.

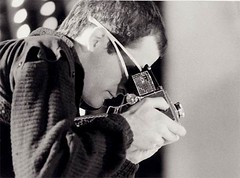

Still, I made sure my camera was ever ready and loaded on the night he was billed to appear. We other performers were allowed to sit stage-left, which is where I was when positioned when Burroughs took the podium. Perhaps I could shoot a candid as he returned from his reading, I thought. Still, I couldn’t help but wish I could take the shot from fairly close-up.

The legless man then came to my mind. I dropped to my stomach, and on my elbows began inching forward, just below the footlights. Another photographer noticed my ploy, and commenced to photograph my progress. When I had finally reached the near proximity of the Invisible Man, he stopped mid-sentence, turned his head and once again fixed me with his stare-of-the-snake.

I focused my camera.

Perhaps just a bit amused, he cocked his head slightly as he looked down on me. He cleared his throat and had just returned to his reading when I seized my moment.

Click.

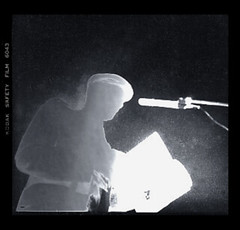

Now I had the precious film, which I brought with all care back to New York. But my hard-won treasure was fated to disappoint all my best hopes. A chance darkroom accident solarized the black-and-white negative. As the final print was pulled from the tray of the stop-bath, what it revealed was a silhouette all ablaze like neon. The outline bore no other features. Once again, “El Hombre Invisible” had evaded the lens.

What I did have in hand, however, was evidence of that random event: William S. Burroughs frozen forever, albeit as a ghost, upon a thin piece of film. Last take: the Invisible Man crosses the Bowery.

“The empty streets, old newspapers in the wind. A rustle of darkness and wires.”