Last week “Beat Memories: The Photographs of Allen Ginsberg” opened at the Grey Art Gallery. The photos of Beat icons amount to a love letter to a lost New York. They prompted novelist Porochista Khakpour to look back.

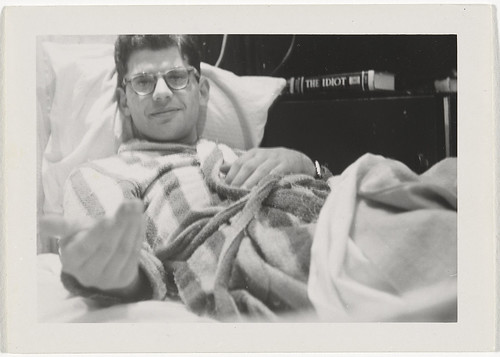

Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York. © 2012 The Allen Ginsberg LLC. All rights reserved.Allen Ginsberg, 1955.

Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York. © 2012 The Allen Ginsberg LLC. All rights reserved.Allen Ginsberg, 1955.The year is 1996 — as it turns out, Allen Ginsberg’s last full year on the planet — and I’m 18 and new to New York. I attend an ill-fitting fancy liberal arts school located 20 minutes north of the city. Every semester I write letters thanking my benefactor for my scholarship and my suitemates remind me their parents pay full-price, and I spend as little time there as possible. Instead, three to four days a week, I take the Metro-North into the city — jump the train, in fact, as another scholarship kid taught me. Many nights I miss the last train back to campus on purpose and stroll the East Village streets and diners and cafes and bars until dawn when I get back to Grand Central.

I care about two things: reading and writing. As a suburban Los Angeles kid, the Beats were my first literary loves and my guide to New York’s downtown life. In my first months in the city, I try to find the corners that resemble my favorite movie (Cassavetes’s “Shadows”) and try to spot the bars and cafés Kerouac and Ginsberg and Burroughs frequented. Some were there; some were not. Cedar Tavern downtown, where Kerouac supposedly pissed in an ashtray, the West End across from Columbia where Ginsberg and Lucien Carr played chess, were all just packed full of kids my age in hooded sweatshirts, hooting over big pitchers of beer — the same set you’d see at a Midwest state school on Super Bowl weekend. I started haunting St. Mark’s Poetry Project and the Nuyorican Poets Cafe, in hopes of finding my own neo-Beat scene but I felt late even to the spoken-word and slam-poetry scene of the nineties, which was approaching its own flaccid fizzle.

One thing remained: Allen Ginsberg. He was still alive and well, it seemed — living on East 12th Street near First Avenue, but you’d see him all over the East Village’s single digits and into the alphabets, often alone but looking like he was rushing to meet someone, someone I’d care about. It was through him that I discovered my favorite coffee shop — the Ukrainian diner Kiev, where 50-cent coffee and borscht became my meal of choice, after I’d encountered the poem in which he canonized the spot with “I’m a fairy with purple wings and white halo/ translucent as an onion ring in/the transsexual fluorescent light of Kiev/

Restaurant after a hard day’s work.”

We’d see him in and out and one time, the inevitable happened: he hit on a young man I was with. He leaned over and looked the dreadlocked white boy in suspenders and combat boots up and down and, ignoring me completely, with the most quaint smile and twinkling eyes, invited my woefully straight friend to his place “anytime.” We went to every reading he gave — and he was still giving quite a few readings, mainly at St Mark’s, where it was always him and his harmonium and glasses, orating and singing and dancing in his seat like a black-lit Day of the Dead merry skeleton. He was electric, uncanny, mad-joy incarnate.

At one reading, a man started shouting from near our seats — an old big guy, who looked semi-homeless. We were all glaring at him when Ginsberg stopped his poem and looked out into the crowd and burst into a big grin: “Gregory!” It was another icon we didn’t imagine had survived: Gregory Corso.

The remnants of the Beat Generation, no matter how dusty and crumbling, were still there in 1996.

And even 1997. That spring, we heard on the radio that Ginsberg had liver cancer. It was me, my boyfriend A, and our best friend — a Brooklynite poet who went by the name Keystone, a dead ringer for the young Ginsberg. We bonded over the Beats to no end; we all wore black and Malcolm X glasses and argued about Artaud and Dada and jazz. This news was devastating to us, to our carefully-selected identities.

Not too long after that, again by radio, we heard he had passed away. It was an April night when we all had work to do, but we were paralyzed. We have to do something, Keystone insisted. We settled on calling the Shambhala Meditation Center where we heard his body was being kept. We asked if we could pay our respects and it was clear many were doing just this — we were not alone.

Not yet.

We made the trip, the last train to the city, knowing we’d be stuck out all night. In the train, we were silent, as if sensing what lay ahead would be bigger than we even guessed. When we got there, it was late — well past midnight, perhaps even 1 a.m., and there was no one there. Just an empty meditation room with a casket and a few skinny Tibetan Buddhist monks.

They seemed apologetic.

Can we pay our respects? Keystone asked again.

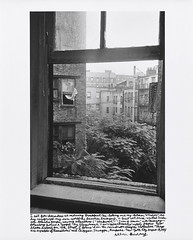

National Gallery of Art, Gift of Gary S. Davis.

National Gallery of Art, Gift of Gary S. Davis.© 2012 The Allen Ginsberg LLC.View out Ginsberg’s window, 1984.

Of course, one tall blond male monk said. In fact, we’d love for you to stay.

Stay?

He looked flustered and red. He explained that since the body had been delivered, things had been relentlessly busy. They were exhausted, in dire need of sleep. Would we mind doing something?

We would not mind, we nodded blindly.

Would we mind watching over Allen Ginsberg’s body? Just till the morning? Of course, a group would be coming in after dawn to set up for his Tibetan funeral then, but if we wouldn’t mind —

We would not mind, we said.

On a sort of zombie autopilot, we took each other’s hands and walked into the room and sat on the meditation cushions waiting for us. And we sat. And we sat. And we sat.

It was the strangest silent night of my life.

We did not get up until the light had filtered in magnificently, and not only were they setting up, but people were coming and people we recognized: Patti Smith, Natalie Merchant, Lou Reed and Laurie Anderson, Kurt Vonnegut, Amiri Baraka, all idols in some way or another. The blond monk motioned for us to remain seated in our half circle flanking the casket. And so we sat some more. Five more hours of his private Buddhist funeral that we had, in one sense, crashed; in another sense, we, his guardians, were essential somehow — part of his story that he was not in on.

We spent over 10 hours with him — this man, this god, who did not know us, none of us.

When we left and bought our bodega bagels and boarded our morning train back to campus, we were still silent.

Did that really happen, one of us eventually said.

I think it happened, another one answered.

Over the next few months, that exchange would come and go just like that.

Sometimes it still shocks me. It comes up again when I see Keystone, nearly a decade since college on a Brooklyn bus, and he still says, I think it happened.

I feel lucky that we were there when we were there — not just the actual event, but the end of that era, the end of Ginsberg’s New York and the beginning of mine. Thank heavens for that ever-so-slight overlap. Since then I’ve lived in three apartments in different corners of the East Village, and like many residents, moaned about the neighborhood’s transformation. But while Ginsberg and the Beats might have left us long ago, I still see those same kids, the train-jumping misfit brainiacs, with the ugly glasses and tattered paperbacks, drunk on borrowed history and in love with past lives, ducking in and out of the streets and stoops and stores and shops, looking for the ghosts who’d invite them over if they were flesh, who were actually honoring their spirit long before they were born.