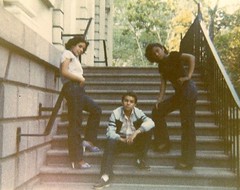

Diana Diaz lives in Park Slope, Brooklyn, but she grew up on the Lower East Side during the 1970s and 80s, and it’s the stories of Puerto Ricans of that time and place that she wants to tell. The N.Y.U. graduate and freelance writer, who grew up ducking into Alphabet City clubs and catching shows at the Nuyorican, has raised funds for a book that she hopes will educate the current wave of nightcrawlers who come to the East Village just “because it’s so gritty” or “because they want to have sex in a bathroom.”

“We have them in our murals, we have them in our kitchens, we have them in our anecdotes,” said Ms. Diaz of the neighborhood’s stories. “But if they’re not written down, our culture is lost.”

Last week, she raised $845 (well over the $525 she was aiming for on Kickstarter) to self-publish “Tales from the East Side,” which she hoped would be the first step toward a wider release.

The collection of “creative non-fiction” recalls a time when Ms. Diaz had to step over hypodermic needles to reach park benches, but it also aims to offer a more well-rounded portrait of the Loisaida of yesteryear. “I think what people miss is that not everyone was a drug dealer. That’s just who you saw because they were on the streets,” said Ms. Diaz, whose family lived on Pearl Street. “Normal people are in their homes, and you don’t really see them. And that’s what I want to talk about — regular people in their neighborhoods, who grew up and had their idiosyncrasies.”

That said, Ms. Diaz admitted that her childhood involved dodging bullets. “It was a weird blend of a very caring, takes-a-village family raising (to this day I’m still identified as my grandmother’s granddaughter) where I was very protected, and knowing when to duck and knowing how not to step on glass and knowing who not to ask for the time,” she said.

Here’s an excerpt from “Tales from the East Side.”

The kids were playing jump-rope under the light, and Rosa made her way over in her coat.

“Can I play?”

“You have to be steady ender.”

This was thrilling to Rosa. Maria dropped the rope onto the hot cement. Rosa’s red eyes lit up as she took the rope’s end into her sweaty, spitty hand, and turned it for everyone else to jump in and out. “Evie Ivy Ovuh.”

She was in a little hog heaven of her own, until suddenly, the girl at the other end threw the rope down and ran off in the direction of building 388. Everyone else was running there, too, but Rosa was used to people flipping the script and running away and changing their plans without her. So she didn’t get there right away, because she first had to get her mother’s permission to follow the other kids. Only after she was given the “I don’t care” hand-wave, did she start over. And then she was slow anyway.

A boy, maybe nineteen, stumbled out of his building lobby, covered in blood, with a knife sticking out of his chest. He ran out into the night and collapsed at the entrance. A crowd gathered, kids first. They measured their importance by who knew him.

“Get his mom —”

She was downstairs in that NewYork minute rarely executed in this neighborhood. We never saw her before. She threw herself over her son. “Mi hijo, mi hijo,” she cried over his chest. Some other boys tried to pull her off, maybe she was hurting him. Blood was trickling from his mouth. Some men – real men, like people’s dads – discussed whether they should just carry him to the hospital, because they’d called the police and no one was coming.

The men were just about to lift him by both ends when two uniformed men pushed their way through the crowd. They were the tallest and palest in the crowd, and the least concerned. One of the men in blue said, “Where’s the guy?”

Where’s the guy?

Before I could feel the gravity of their stupidity, “the guy’s” mom began crying to them in Spanish. The other one said, “What, lady? I don’t understand.” He tried to close his little notepad.

Before that could sink in, there was a small voice from the left. “She said that’s her son. Someone stabbed him. See the knife?” It was Rosa, red-faced and pig-nosed. Standing there in the steamy spring heat in her ridiculous coat.

She had finally arrived.

The woman turned her face to the little girl. She began to speak calmly to her, trusting her with her heavy words and reading the empathy in her eyes. “She says that she sent him out to get bread,” Rosa translated. “They were gonna eat. She gave him money. They must have been watching. They must have been waiting. He’s good, she says. My boy….”

The woman broke down again, and the two men turned to Rosa. “Ask her what’s his name.” But Rosa knew. She didn’t have to turn to his crying mother for the answer. “That’s Hector.”

“How old is he?”

“He’s fifteen.” Rosa’s voice was strong. For the first time, I heard it unwavering. “He’s fifteen. He’s her son.”

Hector’s mother was beginning to explain how her son was so good, he had Jesus Christ himself tattooed over his chest. But the white van finally pulled up, and the police were gone faster than the Queen of Hearts in Three Card Monty.