Preservationists came out in force today to support a proposed historic district that would encompass a large chunk of the East Village, and ran into familiar anger from religious groups.

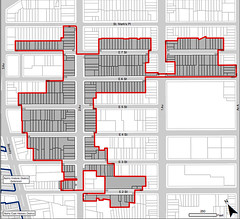

The Landmarks Preservation Commission held the public hearing to collect feedback on a proposed 330-building district that would be centered around Second Avenue south of St. Marks Place and regulate the facades of cultural icons like the La MaMa theater, the former Fillmore East building, and the Anthology Film Archives, among other storied buildings.

At the meeting, which was standing-room only for the first hour and a half, members of the commission listened to about 80 speakers express more support than opposition, with many sporting blue and yellow stickers reading “Preserve the East Village, Landmark Now!”

“As you know, development pressures in this area are intense and getting stronger all the time,” said Richard Moses, president of the Lower East Side Preservation Initiative. “If we don’t act now to save these buildings, they’ll be lost forever.”

Representatives from the offices of City Council Member Rosie Mendez, State Senator Daniel Squadron, Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer, and State Senator Tom Duane also spoke in favor of the proposal, pointing to the need to preserve the rich immigrant history of the neighborhood.

As expected, a number of local clergy and parish members argued against the district, continuing to express concerns about the financial burdens that landmarking would place on their congregations. Some said they worried that they would be unable to bear the costs of maintaining their buildings, or were uninterested in preserving them.

Elizabeth Wright, a parish council member at the Cathedral of the Holy Virgin Protection, said she heard from other landmarked churches that improvements were thousands of dollars more expensive due to their buildings’ landmark status. With obvious emotion, she said she had heard that the additional bureaucracy required by landmarking “siphons off potential funding from other ways in which we can truly do the work of Jesus Christ.”

Father Christopher Calin of the cathedral agreed, pushing back against what he termed the “forced landmarking.”

“For us, it is an intrusion into the life of the church, a wounding of our religious community body, and a sin which you will be held accountable for,” he told commission members. A priest at St. Stanislaus Bishop and Martyr also spoke against the proposal, citing what he thought was a slighting of the Polish community by the commission.

But opponents were generally outnumbered by other local residents who favored the designation. Leo J. Blackman, an architect who has lived in the neighborhood for 25 years, said the district would be acknowledgment that “homes of working class people are as valuable as uptown mansions,” and urged the commission to brush off the religious organizations’ concerns. “We’ve learned the hard way that religious leaders cannot always be trusted to protect their patrimony for us all,” he said.

Landmarks Commission chair Robert Tierney said there was no timeline yet for a final decision about the East Village-Lower East Side Historic District. If approved, the district will join the St. Mark’s historic district, first approved in 1969, and the East Tenth Street historic district, approved just this January.

The commission also landmarked two individual buildings on the Lower East Side today, among 200 others around the city: the Bowery Mission, between Rivington and Stanton Streets, and the former Bowery Bank of New York building at the corner of Bowery and Grand Street. The Bowery itself was added to the State Register of Historic Places in October.