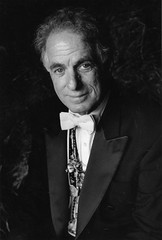

Over the weekend, The Local revisited the 1960s and The East Village Other. Before we return to the present-day, let’s dip back still further in time, with composer David Amram‘s memories of collaborating with Beat legends and jazz masters in the 1950s. This passage, written in 2003, is excerpted, courtesy of Paradigm Publishers, from his forthcoming book “David Amram: The First 80 Years.”

“Go east of Avenue A when you move to New York,” said artist Joan Mitchell, the Summer of 1955 when she encouraged me to dare to leave Paris and come to live in New York City. “Go to the Lower East Side. It still has that soulfulness you are always talking about. Charlie Parker lived there. Artists like Franz Kline, and so many others still do. It’s the real New York. You’ll find it a haven from the Philistines. It’s an island within an island.”

When I came back home to the USA to live in New York, I moved to my sixth-floor walk-up railroad-flat apartment at 319 East Eighth Street (now torn down and rebuilt), between Avenues B and C in the Fall of 1955.

Joan Mitchell was right. The Lower East Side, now called the East Village, was an island within an island. There were still a handful of old men with pushcarts selling vegetables, pots and pans, used clothes and rags on the streets, and even a horse and wagon that was run by a man who claimed to be a gypsy prince who sharpened knives.

Yiddish, Spanish, Ukrainian, Russian, Romany and Polish were so frequently spoken that most of the East Village’s residents could say a few words in all the languages that filled the air. Their tapestry of sounds were accompanied by the delicious aroma of slowly simmering cabbage, blintzes, shashlik, arroz con pollo, pierogi and clouds of various dishes using enormous amounts of garlic and fried onions.

In the spring, summer and fall, the warm sense of community was celebrated with the sounds of radios blasting from the rooftops where people lay on blankets, drinking beer, creating a contrapuntal accompaniment to the sounds of accordion and fiddle players performing folk songs from Central Europe, often backed up by bongo and conga players from the neighborhood who added the Latin rhythms of the bomba and plena from Puerto Rico and the guaguancó from Cuba, as well as improvising jazz artists occasionally joining in. I often sat in with my French horn, pennywhistles or dumbek, playing for hours in Tomkins Square Park. Except for the winter months, when musicians from the neighborhood as well as those I met throughout the city would begin to come by my sixth-floor walkup to play music, cook an improvised omelet, read a poem, show everyone their latest sketches for a new series of paintings, read from the outline of a new play, or just hang out to shmooze.

My rent was $42 a month. All who stayed a while chipped in what they could.

During my first steady job in New York as a member of the Charles Mingus Quintet in the fall of 1955, jazz greats Thelonious Monk, Sonny Rollins, Kenny Dorham, Mary Lou Williams, Charles Mingus, Dizzy Gillespie, Oscar Pettiford, Thad Jones, Bill Evans, Pepper Adams, Julius Watkins, Cedar Walton and Randy Weston used to climb all those stairs of my East Village walk up and spend time, jamming and sharing musical ideas.

Many of us were veterans of the military service from World War II or the Korean conflict. We were drafted and served our country to celebrate freedom. In our own way, each of us wanted to see things continue to move forward, and to embrace the beauty that society at large and the entire New York arts establishment either reviled or ignored.

The East Village was now a place where we could ring the bells of freedom 24 hours a day, and we did.

Towards the end of 1956, I walked two blocks to the Emmanuel Presbyterian Church around the corner, and met Joe Papp, then a floor manager for television shows, who wanted to bring free productions of Shakespeare to all New Yorkers. Joe Papp was putting together a production of “Titus Andronicus,” being done for free at the church.

The cast included Colleen Dewhurst and Roscoe Lee Brown and Joe asked me to write the music. The following Summer of 1957, Joe asked me back for twelve more years, as the composer of the music for thirty productions of what became known as the New York Shakespeare Festival.

At the end of 1956, during the same time that I started working with Joe Papp, pianist Cecil Taylor and I opened up at the Five Spot, an old bar on the Bowery, with our jazz quartets.

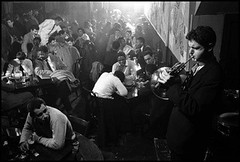

Painters, poets, musicians, actors, sculptors, bus boys, moving men, athletes, lawyers, bus drivers, waitresses and all kinds of assorted dreamers would gather every night, often participating in some way with my quartet. At the old Five Spot, spontaneity was practiced, not preached.

“The Tonight Show” and Esquire magazine came down and filmed me there, and the Five Spot became a new jazz mecca.

Jack Kerouac sat in with us the first week of January of 1957, just before he shipped out to Tangiers, after finding out that “On the Road” was finally going to get published that coming September. He read with us and played bongos.

We had already collaborated at many Saturday-night bring-your-own-bottle parties at various artists’ lofts in the East Village, during 1956. In October 1957, we gave the first-ever Jazz/Poetry reading in New City at the Brata Art Gallery in the East Village.

Two years later, in 1959, Jack and I took part in the classic documentary film, “Pull My Daisy,” shot in artist Alfred Leslie’s East Village studio. It was filmed a few minutes from the Five Spot.

The crazy cast consisted of friends who hung out together whenever we could, in our island within the island of the East Village, celebrating our latest thoughts with one another in nonstop discussions and arguments about art, literature, baseball, politics, music and how to find the perfect soul mate.

Out of these gatherings at the Five Spot, the Cedar Tavern, tiny coffee shops, park benches, and each other’s apartments, the creators and cast of “Pull My Daisy” naturally evolved. Jack’s stream of consciousness narration, my score, and the crazy antics that we all did spontaneously on camera were the way we actually were when we all hung out together in real life.

Kerouac and I would often go after a night of carousing at 4 a.m. to nearby Bickford’s, the greasy spoon and high-cholesterol philosophy center, to greet the dawn, chowing down with East Village anti-hangover specialties: hamburgers with fried onions and mayonnaise on an English muffin, with lots of steaming black coffee.

Some nights, Bowery bums and the short-order cook would join us in our conversations, reminding us that the East Village was never an Ivory Tower, and that we should honor the sense of community as well as the unheralded beauty that surrounded us in the grimy but endlessly rich street life of the East Village.

We loved being there. Our mantra was “Never go above 14th Street.”

Folk music also had roots in the East Village of the 1950s. Dave Van Ronk and John Hammond used to come to the Five Spot when I played there when they were kids.

I met Woody Guthrie in the Spring of 1956 at an apartment around the corner from where I lived, introduced to me by Ahmed Bashir, a friend of Charlie Parker and Sonny Rollins, who was staying with me at the time.

After Woody told us stories about his Oklahoma youth, and how old cowboy songs and church music were such an important part of Western American rural life, Ahmed Bashir sang Woody some Muslim prayers and I sang some Sephardic songs for him.

This kind of meeting could only have happened in the East Village.

In 1959, as the decade ended, Miles Davis recorded “Kind of Blue,” the same year that “Pull My Daisy” was made. Both events were a valentine as well as a farewell to the ’50s, and a community that we loved.

We hoped that our collective spirit and all the work we did would sound a wakeup call to a slumbering America, telling everyone that we needed to love ourselves as well as each other, to support each other’s dreams, and make the gardens bloom again. Those of us blessed to still be here today, nearly sixty years later, hope that what we did then and still do today will inspire new generations to create their own island within an island, and their own generational art and sense of community, just as we inspired one another to do.