It’s a fitting time for the revival of a thirteenth-century play with corruption in Chinese bureaucracy at its heart: Last month, Chinese official Bo Xilai was suspended from the Politburo, the twenty-five member committee that rules China by fiat, following allegations that he wiretapped President Hu Jintao. Meanwhile, Mr. Xilai’s wife stands accused of murdering a British business consultant.

It’s also about time that China’s growing influence on the world and cultural stages be reflected in a more well-rounded way than it was in “Chinglish” – the comedy about a Cleveland sign-painting company looking to expand to China whose characters were “about as personally involving as the brightly colored, illustrative figures in a PowerPoint presentation,” according to the Times review.

Unfortunately, the Yangtze Repertory Theatre of America’s production of “The Chalk Circle,” now at Theater for the New City, doesn’t even rise to the level of “Chinglish.”

“The Chalk Circle” is the story of a young prostitute, Begonia Zhang (Denver Chiu), who is forced to sell herself to save her family from destitution. She becomes the concubine of the wealthy “Official” Ma (Al Patrick Jo) whom she eventually marries.

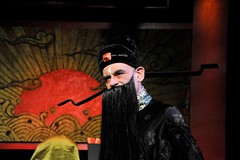

The story is told in flashbacks: when we first meet Begonia she is in chains, about to be sentenced for murdering her husband in order to take his first wife’s inheritance and son. But it’s actually the ex-wife (Shu Mei Kwan) who’s the criminal, having framed Begonia and bribed witnesses and court officials in the case. The first wife eventually gets her due, thanks to the great wisdom of Judge Bao (Bill Engst).

This intervention by an upstanding official is a pleasant fantasy, given the on-the-ground realities of present-day China. And that might have been fine, but the theater is a workmanlike black box with a utilitarian set and costumes to match, and the singing – which is minimal – comes almost exclusively from Denver Chiu’s lungs in the role of Begonia. All we are left with is caricatures and clumsy exposition, without any romance or beauty to make up for it.

The Yangtze Repertory Theatre should not be faulted for not having the resources to produce the kind of million dollar sets that the Met built for its latest production of the “Ring Cycle” (to take an example from opera); Shakespeare’s Globe had no sets to speak of, but Shakespeare had the advantage of soaring language.

As for the acting, it does not encourage either. Mr. Chiu, the founder of a Chinese luxury cosmetics company who flew all the way from Hong Kong to play the lead female, is a bold choice for the role. Why was he called upon to enact a tradition that began to evaporate in the 1930s with the integration of actresses as company members? According to a bio in the program, Mr. Chiu is responsible for the “singlehanded revival of the art of an actor playing a female role,” and was a member of Hong Kong Repertory Theater in the ‘80s, but one feels that this was not a piece of strong casting.

It seems that in the adaptation of the drama from classical Cantonese to modern colloquial parlance (much of the dialogue is in standard American English) a world was lost. The production translates thirteenth century China to the present in a way that makes us wonder less about what we saw, and more about what might have been.

The Yangtze Repertory Theatre of America’s production of The Chalk Circle plays through May 20 at Theater for the New City (155 First Ave.); 212-868-4444

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this post misidentified the play as an opera, and the author’s criticism was based in large part on this misperception. The play is in fact a work of Zaju, a genre of Chinese theater that combines dialogue with singing, acrobatics, mime, and dancing. The author, who stands by his general assessment of the work, made revisions to the original post to better reflect the play’s historical and artistic context.