It’s the last day of National Poetry Month, so here’s the final installment of our interview with Bob Rosenthal, conducted at Allen Ginsberg’s old 12th Street apartment, where Mr. Rosenthal worked as his secretary for nearly two decades. (Parts one, two, and three of this leisurely conversation ran last week.) As Ginsberg grew older and ill, his assistant followed him to a 14th Street loft purchased from the painter Larry Rivers; when Ginsberg died in 1997, Mr. Rosenthal became executor of the poet’s estate and guardian of one of his last meals.

Allen’s Addictions

Allen always had some pot around – he was a pot propagandist and so if a joint was being passed around and someone was going to take a photograph he would grab the joint so he’s got it. But actually, I rarely ever saw him smoke. He had pot for boyfriends – it’s a good line: “Oh, you want to come up and smoke?” It was really for them. He would go to LSD conventions with the big guys – the Fitz Hugh Ludlow Library guys, Huxley and all those guys. They would give him acid and he would come home and put it in the refrigerator and that was cute. There was a little vial of LSD and it said “Do not take without permission of Allen or Bob” – so I guess Bob had permission. So that was nice. But I never saw him on LSD.

He was a workaholic. He didn’t like alcohol – it killed Neal and Jack and Trungpa. And he didn’t like speed. He had a set of works in his drawer under the bed. I actually still have that because you can’t sell that stuff. We have the drug paraphernalia – some nice roach clips and things like that. And I’ve had European buyers, but I’ve said, “I can’t send it in the mail,” it’s actually illegal. So I said, “You have to come and you have to get out of the country.”

One of the things Allen said to me before he died was, “Don’t make a museum out of me,” but when we moved out of this apartment we had a tool box and I put in all this little bric-a-brac (coins he had gotten, little medallions he had been given, things he got while traveling, his drug paraphernalia) and I call it the Beat Museum. It’s kind of a joke but it actually is – it’s a little treasure chest full of oddities. And so we still have that.

But no, Allen was a workaholic. So he always had Demerol and that was so he could get up on the stage and read, and that was so important to him. Above all things in this world, he loved to get up on the stage and give a reading to college students. It wasn’t the money – it was the applause. It was the communication. My pop psychology sense is that he had this psychotic mother, Naomi, who had her first breakdown even before he was born. Maybe she couldn’t mirror well, maybe she couldn’t give him a proper well-balanced narcissistic self so he needed affirmation – he needed applause. Luckily he doesn’t go around shooting people to get attention, he wrote poetry to get attention. And great poetry. And got great amounts of attention. So it was all really good.

But even when he could’ve stayed home and taken care of his health, he went out and did readings. Readings he just could not say no to. He could’ve just sat at home signing his photographs and made more money, but it was never about the money, ever.

The Million-Dollar Question

When he made the sale to Stanford, he got attacked in the New York Times three times, in three different sections, three different ways. Some guy wrote an op-ed: “Oh, well he should’ve given it, blah blah.” I mean he was living here – he could barely make it up these stairs. I got Simon downstairs to agree to be on call whenever Allen was coming in at 3 a.m., to help Allen carry in his bags. But you would walk up with him and he’d start telling you a story and the middle of the story would always be about Kerouac or something – “and then Jack said…” – and of course you stop and you lean in, you want to hear that story. He’s just breathing. The whole story is an excuse to catch up on his breath. It was so hard.

It was really important to get him in an elevator building – why shouldn’t he have a little comfort? I truly tried to figure out why there so much anger. And I think it’s that basic east-west rivalry – that it should’ve gone to the Berg [Collection of English and American Literature], but we got screwed by our book agent who said he had approached the Berg at the New York Public but he actually never had. And I don’t know if the Berg would’ve bought at that time.

Stanford was in acquisition mode – they acquired Levertov, Allen and Creeley all really close together. And they paid a price, and they didn’t quibble; and it’s a new building, it’s air conditioned and well cared for. It’s not a bad thing. Ironically at Stanford is the Hoover Institution, which has all the paperwork of the former Soviet Union, so it’s kind of fitting that all of Naomi’s paranoid hallucinations would be documented in the Hoover Institution and there’s Allen’s papers right across the hall.

The Gap Ad

In the Gap ad, there’s a very small disclaimer that says all the money is going to the Jack Kerouac School. It actually got Denver impoverished youth a summer program at Naropa but it didn’t matter, people were really mad because I think Allen had a really pure persona – he was above it all, he wasn’t commercialized. William Burroughs had all sorts of ads, actually. Nobody cared. It never mattered about William but with Allen, people resented the idea. Allen had to walk around with this persona he created that was a mixture of pure and earthy – he had to live with that.

Allen took money from the Rockefeller brothers and gave it to Naropa – his idea was very much akin to Chögyam Trungpa’s idea that you take the bad money and you make it good; you take in the poison and you breathe out the nectar. It didn’t bother him. It just rolled off and it didn’t last that long and when Microsoft used the same picture in some kind of ad (I’m pretty sure it was Microsoft) when they figured out he was using the money for charity they doubled him up. And so $10,000 became $20,000 – that all went to Naropa. It was good. I think people in the world of money understood and they liked the idea.

Allen on Film

I think a lot of “Kill Your Darlings” is taken from his journals, so I’m hoping it’s more of an intelligent treatment of the story – less sensational. He liked David Kammerer. He was sorry that David Kammerer was killed. I think it’s going to be a little bit more even – it’s not just going to be the “honor slaying.”

His experience with the movies was when they were making “Heart Beat,” the Carolyn Cassady story, and they sent him the script and there’s a young Allen Ginsberg drinking coffee and pounding at a table going, “Moloch! Moloch! Moloch!” And he was so offended that he said, “Take my name out.” So they left the character in and they changed the name, but it was something close; and he realized it’s better just not to mess with it. You can’t control it, just let it go.

One thing I’ve noticed: Allen always comes out reasonable and nice in these movies. He’s always seen as the sane person. And I think that’s the way he really was, I guess, even though Kerouac’s treatment of Allen is not very complimentary in “Desolation Angels.” The Carlo Marx character is obnoxious and I think he truly was an obnoxious young man, but he was so young and I never knew him then. I only met him after years of Buddhist meditation. He had calmed down.

When he wanted to get angry about plutonium – the Rocky Flats trigger factory in Colorado – he wrote it, but he couldn’t find the old anger, he had kind of meditated that anger away. So he had to create anger through craft and editing. And I think “Plutonium Ode” is a really strong poem and it has great parts and I think the fourth section about advice to the poets of the future is really spectacular. And it stands up well. It’s like a baseball pitcher; you get a lot speed when you’re young but then you have to learn how to pitch.

Watching Allen Work

Neither Allen nor I could spell. I was so lucky to find a boss who couldn’t spell either.

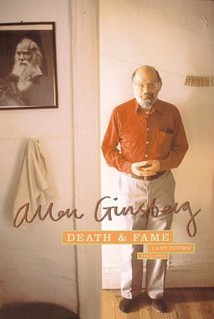

I didn’t presume too much to tell him how to write – he was pretty much always the master. But I got to contribute to some of his poems. Like right at the end when he wrote “Death and Fame” – it’s a poem envisioning his funeral and what everybody says. I remember I was going with him to Boston to see his cardiologist. It was at night and it was raining. It was one of those cab drivers who was driving too fast and stopping too short and I was getting seasick and Allen said, “Here, look at this.” He’s showing me the notebook and I said, “Allen, I can’t read – it’s dark.” So he starts reading it to me and he’s breaking up and laughing and after I heard a bunch of it I said, “Oh, and the girls say, ‘He never did know my name,’” and that line made it in.

I think on the liner notes and things like that I would have input but otherwise, not so much with poetry. That’s Allen Ginsberg – I’m not fussing with it. I was happy just to be able to type it. On the plane that same time he fell into a deep sleep – I mean, it was like dead asleep; I was actually worried whether he was going to wake up – and then he woke up with a start and grabbed his notebook and wrote down a little couplet which is actually in one of the books. I don’t know if it’s collected in a group of poems but it was “my father dying of cancer, oy, kinderlach, the little kids,” and that still kind of stunned me – here I am witnessing this. I think I was always a little bit in awe of Allen, though very comfortable.

I never showed him my own poetry and I don’t know how I was smart enough not to do that. I know he had his own protégés and I realized I had to promote them and I didn’t necessarily always like their poetry and it would just make it hard if I was jealous of them. I think he was relieved that I wasn’t foisting that between us.

The Last Soup

Allen liked to cook soups right here at the sink. He liked to go shopping. When he was on 13th Street, I had a guy set up to be his car service chauffeur, I had a housekeeper who did all his cleaning and shopping for food, and he had a bathroom with a bidet.

Everything was laid out and open and he designed translucent windows between rooms so that the inner rooms would get light and not have to be lit by overheads. And there was a mud room when you came in so there was a bench and cubbies: you’d take your shoes off when you come in and stick them in the cubby. He was in the big room – he had the office in the back. I learned how to check his insulin, how to shoot insulin – I was trained by a diabetic counselor. And I was going to marshal his time as a resource. So if someone came in to interview him I’d say, “You have 90 minutes.” I’d come in at 90 minutes and cut it off. I would save his energy. The world would come to him. But we only had a couple of months of that.

One of the last things he did in his life was he had this soup. He called my wife. She had a made a fish chowder for him and he liked it and so she gave him the recipe. He liked seafood, so he went out and he got all sorts of clams and scallops and all sorts of seafood and he starts throwing it all in, with the clams in the shells – I don’t think they were really washed. Usually he was very sanitary about things but this was his last soup.

One of the things he built in the loft was a soup cooling rack outside one of the windows: it was a rack that hung out there so you could put a big pot of hot soup out there to cool – a unique feature in anybody’s apartment. So he made this soup and I refused to eat it but he served it to a couple of people and they said it really wasn’t very good. And then we froze a lot of it and then he died.

I cleaned out his apartment and one of the last things I cleaned out was his kitchen – it was actually, strangely, the most emotional. You’d think his library would be, but no. His spices, his dried mushrooms, his supply of peppercorns, all that stuff – that was really moving. His cookbooks and then the soup in the freezer. And I thought, “I can’t throw this soup out. It’s like there’s something about it that’s interesting.” I knew that food anthropology was kind of a new thing and I thought maybe somebody would want it. I had a friend Jason Shinder, who has unfortunately passed away, but he was a genius; ran the Writer’s Voice at the Westside Y for years and could really figure things out. I gave him a task: find a place that’ll take the frozen soup.

He actually did – it was this museum of oddities in California, but because of earthquakes they couldn’t guarantee that the electricity wouldn’t be cut off to the refrigerator and so they ended up not taking it. Meanwhile there was a squib in the New Yorker about Allen’s last soup – that was fun – but I still just want to do a movie where you get a food anthropologist and bisect it, talk about it. We have the original shopping list for it, the housekeeper who bought it, and Shelley could talk about it. Now it’s in my freezer on 10th Street where I live.

Last Poems

He became a little addled and he was writing nursery rhymes. He asked me to bring a copy of “Mother Goose” and I went through my kids’ old books and I found my old “Rackham’s Mother Goose” and brought it and he was looking at it and said, “Oh yeah, see? This little piggie went to market, this little piggie stayed home.” Then he said, “What about that third little piggie?” And I said, “That little piggie had roast beef,” and he said, “Ha! Pigs don’t eat meat! It’s a change.” And then he rewrote it to say, “This little piggie had quiche.” Of course, he’s wrong, pigs eat meat – but that was beside the point. He was rewriting “Mother Goose,” and rather well.

And they were flowing out of him – three or four poems a day at the end, until he finally got the fatal diagnosis that he had months to live and then he only wrote one poem in a week, and it was a poem of regret. On the website you can actually see a holograph of that poem. It was the only poem he never got to see a typed copy of to correct, so there actually are some words we never figured out. But we think we have them all now.

As told to Daniel Maurer. Interview has been edited for continuity. Read the first three installments here.