Daniel Maurer Bob Rosenthal in the hallway of

Daniel Maurer Bob Rosenthal in the hallway of437 East 12th Street, with Ginsberg

over his shoulder.

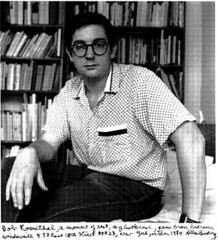

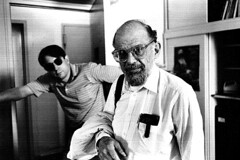

With just a few days left of National Poetry Month and a movie about the Beats in the works, it seems an appropriate time for Bob Rosenthal, former secretary to Allen Ginsberg, to share some memories of his former employer. After all, Mr. Rosenthal, an East Villager and a poet in his own right, recently completed a memoir titled “Straight Around Allen” (it’s being shopped to publishers) and he appears in “Passing Stranger,” a recently released audio tour of the neighborhood’s poetic landmarks.

It just so happens that the editor of The Local lives in Allen Ginsberg’s former apartment on East 12th Street – or rather, the portion of the apartment that contained the poet’s bedroom, bathtub, and the home office where Mr. Rosenthal worked alongside the literary legend for nearly two decades. Yesterday, Mr. Rosenthal, who these days teaches Beat literature to high schoolers, paid his first visit to his old workplace in some years, and spoke candidly about his time there.

Bob Moves to 437 East 12th, Allen Follows

My wife and I moved to New York from Chicago in 1973. We were living on St. Marks Place and met people in this building [437 East 12th Street]: Rebecca Wright, a poetess who was actually living with John Godfrey upstairs, was going back to somewhere in the Midwest where she’s from with her son and she was leaving me the apartment. It was like $125 per month and she said, “I’ll leave you these books” – all of them Allen Ginsberg books. She said, “I don’t need them anymore.” That’s when I started reading him. It was serendipitous.

My wife was working at the Poetry Project – she was a secretary. Allen, who was living on 10th Street at the time, called and he needed somebody to type a document for him, and it turned out to be a habeas corpus for Timothy Leary, who was lost in the California penal system. And when we saw what it was, Shelley typed it and we didn’t charge anything. And Allen came over here and said, “By the way, we’re looking for an apartment.” We knew the Brugalettas were leaving and said, “Oh, there’s an apartment upstairs, but don’t tell the landlady, Mrs. Seeliger, that it was us because she hates us and we’re part of the tenant’s organization.” And Peter and Allen came over and charmed Mrs. Seeliger, and got this double apartment for $160 a month.

It’s interesting – he got out of that apartment on 10th Street because he didn’t want to buy it – it was probably ridiculously cheap.

In 1977, I moved to 11th Street. I never lived in this building and worked for him at the same time, because that would’ve been too much; he would’ve knocked on the door at 3 a.m.

Bob Starts Work

I started working for Allen in ’77. When I started here, I was temporary. Ted Berrigan was my mentor and lived on St. Marks Place. Allen called Ted and said, “I need a temporary secretary,” and Ted recommended me.

I was not a big Beat fan – even then, I was a New York school of poetry fan: James Schuyler was my hero, Frank O’Hara and Ashbery and Kenneth Koch. I had read Ginsberg and thought it was really good but I wasn’t aspiring to be in the Beat world. But Allen liked me and he liked that as a fellow poet I was a little bit more upbeat. I was friendlier than the [William] Burroughs people, I was a little less suspicious – I was a little bit more like Allen in that way. He liked the way I talked to people. Very quickly he gave me financial equality – I could write his checks; he gave me a letter to give to the head of special collections at Columbia so I had full access to the stacks.

Allen’s Daily Routine

When I started, I would come in the late morning and pick up the mail at Stuyvesant Station and bring it here and sort through it and he would be getting up in the early afternoon. He’d do a little sitting meditation; he’d be reading The New York Times, sort of puttering around in his underwear. He really wouldn’t become fully charged and awake till about 5 p.m., usually around the time I sort of wanted to go. Around 7 p.m., he was really awake. But we’d work in the afternoon and I’d be taking the phone calls and things would be coming in.

I didn’t socialize much with Allen. When I first started working with him my wife was pregnant, so I had a baby really soon and I was turning 28. He would go out, meet people, usually have a late dinner at the Kiev around 1 a.m. or 2 a.m., go by the Gem Spa, pick up The New York Times, come home, read The New York Times, write in his journal; writing poems or journal entries till about 5 a.m. or 6 a.m. By sunrise he’d probably be getting a little sleepy. He didn’t sleep that much. And he’d start that whole process again. At night, he was probably mainly reading Buddhist texts. He had pretty much done the major literary reading. He had an incredible backlog of memorized poems; he could recite Wordsworth and lots of other poetry.

Allen’s Reading

In his bathroom were political magazines – Spy vs. Spy, COINTELPRO, kind of radical politics magazines: the magazine that Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting puts out, War Resisters League newsletter, I.F. Stone’s Weekly. That was the bathroom reading. He had bookshelves in the bedroom, too, containing most of his friends – that’s where he had Kerouac and Burroughs and people like Philip Whalen. He really wasn’t that adventurous in his reading. He didn’t read novels, he didn’t read plays, but he kept up. Around his bed, a lot of poetry magazines were piled up. He probably couldn’t get to them all. He liked August Kleinzahler: he didn’t always like just the known poets. He championed some lesser known poets.

The Phones

The phones here were always ringing. In “Reality Sandwiches,” one of his poems is “I Am a Victim of Telephone.” His number wasn’t listed, but it was 777-6786; it was so easy to remember. When lunatics broke out of their straightjackets they’d run to the payphone and call, and I took a lot of those kinds of calls. That was one of my jobs.

The phone calls were always interesting: Carl Solomon being a walking messenger, and kind of crazy and calling on every corner saying, “Allen ruined my life! He ruined my life!” and then: “Aw, it’s okay.” He would just be vacillating. We recorded these things – kind of crudely. We just had a cassette recorder and a cassette answering machine and I also had a little suction cup recorder. But if they left messages, I would just play it and open-air record it on the cassette. So at Stanford [home to Ginsberg’s papers] there are a bunch of those cassette tapes full of messages – Gregory Corso and Carl, all sorts of people. Everything was documented. Allen had recorded a phone call he had with Kerouac – it was the only Kerouac thing he recorded – on reel-to-reel tape. We could never find that tape. It was like the lost tape.

When Allen quit smoking, he was terrible. And he quit smoking a lot. He was like a little kid: “Where’s my glue?”, “Where’s my pencils?”, “Why wasn’t this done?” He would have temper tantrums, but that was it: he’d just flail his arms for a little while. And so I would answer the phone and they would say, “Is Allen there?”, and I’d say, “Gee, who’s calling? I’ll see if I can go find him.” Meanwhile he’d be sitting next to me, and he would immediately start saying, “Tell them I’m quitting smoking! It’s a genuine disease! It’s a real syndrome!” And then I’d say, “Allen’s indisposed right now…”

The Mail

Getting the mail was a big thing. The most memorable piece of mail was a certified letter, a manila package, from John Clellon Holmes. When I opened it up, it was the first manuscript of “Howl” that had ended up in John’s hands. I looked at it and I didn’t recognize it because it was in William Carlos Williams triadic lines, but it didn’t take me long to realize what I was holding. That was very exciting. That was a centerpiece of our sale to Stanford, too.

There were a lot of weird fan letters too – a lot of ladies writing “I can cure you of this homosexuality if you let me.” Allen said, “Only my brother and my mother are Personal.” Friends would write “Allen only,” “Allen’s eyes only,” “Personal.” It was only Eugene and [step-mother] Edith who got that treatment. Everything else, I would slice them open, lay them out, get them out of the envelopes.

Allen saved the junk mail. We sorted the mail into Business, Personal, Literary, and Junk. Then we’d hire a poet to come over and go through the junk mail and write a poem about it, but actually looking for any mistakes like some good letter that had dropped in there by accident. About four or five of the poets around here wrote junk mail poems. Ted Berrigan, on his death bed, was working on a junk mail sonnet. The whole idea of taking three shopping bags full of Allen’s junk mail and turning it into a sonnet is great. Allen’s model that he learned in India was the cottage industry: he wanted to hire poets; he wanted poets to survive. So, soon I had an assistant, and I had two assistants and they were cataloging tapes. One of the rules was that every reading Allen gave should be audiotaped. Not well audiotaped – just some cassette deck thrown on the stage. Those tapes would come in and not even be listened to – they’d be cataloged and put away, and copies of catalogs were made and retyped. Allen was really into filing and retrieval, so he loved having secretaries.

We’d do all the social actions – writing letters to the governor, writing to organizations, foreign heads. I learned how to write an Allen Ginsberg letter using Buddhist buzzwords: mindful, grounded… I was getting pretty good and he would sign them and that made me feel good because he would get answers. It made more sense for me to help him write letters than for me to write letters.

The mail was huge – he would come in from being out on a reading trip or something and I’d have a stack of mail to read and I’d prioritize it from important to least important. People sent him what we’d call the Mad letters – that was another category. Those would be the single-spaced handwritten letters – six pages, 12 sides – and he would turn the pile over and he would read those first and he would spend hours pouring over these Mad letters and he would proudly show me, “Look, it makes sense! First it says this and then it says that, and then it goes there.” And I would say, “Great, Allen. Well, do you want me to answer?” And he’d say, “Oh no, don’t answer! They’ll write again!” But because there was madness in his family it was a faculty he had. He would have been a phenomenal lawyer – he was the best contract reader I ever met, and a great negotiator and great mediator between people. Thank God he was poet instead, but he had tremendous skills.

Office Music

When he was young, Allen had a lot of classical records, Indian records, a lot of blues. He loved Ma Rainey. Ma Rainey was his musical hero and after that maybe Bob Dylan. We played Ma Rainey when he was dying. It seemed like the right thing to play. In early pictures of him in San Francisco you see his room and you can see he has Bach’s “Mass in B Minor” – he was listening to classical music. But he didn’t come in and put music on – in fact, he would listen to AM 880 while he was shaving or grooming himself. He just liked to hear a little bit of the news all the time, like some people might have CNN on all the time.

Allen’s Finances

Allen hated accumulating money – he didn’t have savings accounts; whenever he needed money, he just made more money. But he had a wonderful facility for making money. He could go out for readings, he could sign photographs, he could publish books, he could do talks – anything. He was very generous. He lived a life of poverty but he made a lot of money – he was making $300,000 a year. I was paying more taxes, just like Warren Buffet’s secretary. He kept every receipt and when it was all totaled up, he paid very little taxes. It was by design: Allen didn’t want to pay any tax for war, so any money he paid he either hired secretaries, wrote off on taxi cabs, books, whatever, and basically he made about $6,000 a year after everything worked out and he paid no taxes.

Most of his reading fees were put into a non-profit, the Committee on Poetry, and then he gave that money away. So he supported a lot of people. He didn’t want things. He finally got a little T.V. (across Avenue A was a French lady who had a little video shop) and he got a little gay pornography, but that was about it. He didn’t watch T.V. People would ask him, “What do you think of Dobie Gillis, Maynard G. Krebs?” He would go, “Oh, Maynard G. Krebs – late 1950s stereotype of beatnik character.” He had a memorized response, but he never saw it – he wasn’t aware of it.

As told to Daniel Maurer. This interview has been edited for continuity. Read the second, third, and fourth parts here.