The funniest part of reminiscing about the uber-subversive East Village Other for The New York Times is that the latter set me on the road to rebellion before the former was even founded in 1965. I’m told I was reading by age four and within a few years the first section I grabbed when the Sunday Times arrived every weekend was the Book Review. The Grove Press ads kidnapped my imagination: Who was this Alain Robbe-Grillet guy and how do you pronounce his name? Why was William Burroughs considered so dangerous and did his characters have meals while wearing no clothes? And speaking of clothes, how come the girls on Grove’s covers wore so little?

Obviously my nascent libido was ready for plucking, but my fascination was not simply sexual. I wanted to know why in the land of the First Amendment some had wanted to ban these books.

I bought my first issue of the Village Voice in February 1966; it contained an obituary of the abstract expressionist Hans Hofmann. Already a Dylan fan, I scanned the ads for folk clubs and was absolutely smitten by bohemia. The first girl who won my heart in elementary school was Jessica Hentoff (I don’t recall my feelings being reciprocated) and her father Nat wrote for the Voice. Soon I picked up the Voice’s competitor, The East Village Other.

No friends’ parents wrote for EVO. Scruffier, funnier and dirtier than the Voice, EVO was not simply about bohemia, it was an anarchist’s bomb in newsprint hurled at the bourgeoisie. Even at my tender age, I knew that I didn’t like the world that grown-ups had created. The troublemakers at The Other were expressing themselves in ways I could only daydream about at that point.

I turned 12 at the beginning of 1967’s Summer of Love. When you’re born as strange as I clearly was and the largest mass bohemian movement in human history invites itself into your consciousness, you set a place for it at the breakfast table and bring it with you to bed at night.

Generally speaking, parents don’t like mass bohemian movements. My folks were neither prudes nor right wing. They were Stevenson/Kennedy liberal New York Democrats with show biz and jazz roots that had exposed them to all sorts of outré behavior. However they were not amused that their adolescent son was cackling over a photograph in EVO in which a male hippie stood frontally denuded, arms joyously outstretched on top of a tenement roof.

I considered myself a true believer and thus felt compelled to turn people on to the inevitable wave of universal LOVE that was going to sweep the planet and permanently change the course of human history. The hippie was Tuli Kupferberg of the Fugs and in his accompanying text, “Uncle Tuli” — who at the ancient age of 43 was dubbed “The World’s Oldest Hippie” by Allen Ginsberg — advocated a “Kiss Corps” of nubile hippie chicks who would defuse crime and violence with smooching and more. Such was the utopian (and pre-feminist) ethos of Flower Power in that glorious year of 1967.

It was while I was explaining Uncle Tuli’s enlightened theories about law enforcement to my parents that they caught a glimpse of the photo that revealed Little Tuli to the world — or at least to the readership of The East Village Other.

“Disgusting!” sneered my father, grabbing my EVO.

“Revolting!” seconded my mother.

“So what?” I shrugged. “It’s just Tuli.”

“What is a Tuli?” asked my father, unsure whether I was referring to the nude’s name or perhaps a newly minted anatomical reference.

I told him the truth: “He’s a Fug, Dad.” I explained that the Fugs were a rock band who wrote songs both political and satirical. (I neglected to mention their back catalogue of smut-rock.) My father rolled his eyes and handed me back my copy of EVO as well as my constitutional right to be me. Part of the fun of being young is deliberate contrarianism and the Fugs were so contrary that many publications wouldn’t even print the name they borrowed from Norman Mailer’s fornicatory euphemism in his WW II novel “The Naked and the Dead.”

Tuli was beloved by younger hippies like me for his unshakeable bohemianism — as captured in his rooftop striptease. (It’s interesting how repressed America was back then while now everyone gets naked on the Internet. There was a time when disrobing publicly was a political act.)

Deliberate contrarianism was also a hallmark of The East Village Other. Whether it was the cartoons of Robert Crumb or the underground luminaries who provided the text, EVO delighted in offense. Even during the Summer of Love, EVO contributors carried their flowers in a fist, to paraphrase Abbie Hoffman. But then EVO was a New York newspaper through and through that never lost its tough streetwise attitude. Even Tuli’s pacifistic advocacy was pro-active, meant to upend the middle-class Big Apple carts.

For young New Yorkers of the ‘60s and ‘70s, EVO spoke for us, in our voice, with our insolent sense of humor, our passion and all the certainty of youth that we could change the world. We may have succeeded in small ways while failing to make larger, lasting change, but as Yogi Berra said, it ain’t over ‘til it’s over. The Occupy movement may want to reconsider Uncle Tuli’s Kiss Corps. Perhaps we can iron out the kinks (so to speak) in order to minimize sexist perceptions. After all, to make love in the 21st century is still preferable to waging war.

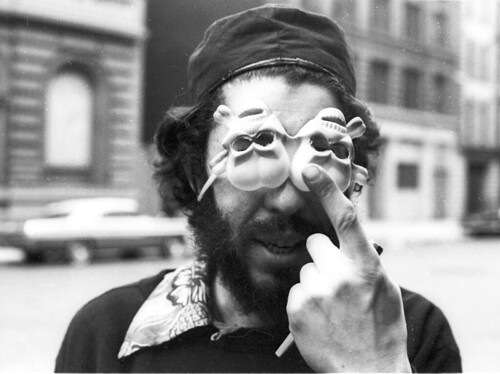

Musician, writer, filmmaker and activist Michael Simmons (shown here in 1972) was dubbed “The Father Of Country Punk” by Creem magazine in 1976. For his investigative reportage on the Hollywood Vice Squad in the L.A. Weekly, he won a Los Angeles Press Club Award in 1996 while also covering the national medical marijuana movement and the Zapatistas in Mexico. In the last few years, he has profiled George Harrison, Bob Dylan, Leon Russell, Lowell George & Little Feat, and The Fugs (both collectively as well as co-founders Ed Sanders and Tuli Kupferberg separately) for MOJO magazine, the L.A. Weekly, the Huffington Post and elsewhere. He’s producing a documentary called “YIPPIE!” about Abbie Hoffman, Paul Krassner and their fellow political pranksters and is currently wrapping a solo album called “Last Call At The White Horse.”

For more on “Blowing Minds: The East Village Other, the Rise of Underground Comix and the Alternative Press, 1965-72,” read about the exhibition here, and read more from EVO’s editors, writers, artists, and associates here.