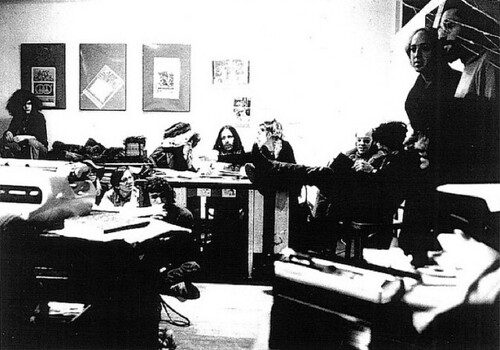

Left to right: Steven Kohn, (on floor:) Heather, R. Crumb, Ray Schultz, (sitting behind:) Hetty Maclise, John Heys, Coca Crystal, Allen Katzman, David Walley, Little Arthur, (standing:) Joel Fabrikant, Jaakov Kohn

Left to right: Steven Kohn, (on floor:) Heather, R. Crumb, Ray Schultz, (sitting behind:) Hetty Maclise, John Heys, Coca Crystal, Allen Katzman, David Walley, Little Arthur, (standing:) Joel Fabrikant, Jaakov KohnThe end of my real involvement with The East Village Other came as something I perceived as a betrayal. I have come to think I really didn’t understand it at the time and perhaps what happened wasn’t directed at me personally. But sometimes I wonder.

I mentioned in my earlier piece that EVO was formed as a stock company, with Walter Bowart, Allen Katzman and I each owning three shares.

“We need to raise more money,” Walter said to me in the spring of 1966. “We’ve run out. I’ve called a meeting and there will be new people coming. We need to get more people buying stock.”

“It won’t dilute my one third, will it?” I asked.

“It doesn’t have to,” he said, “if you buy some more, too.” And this was technically true.

The meeting took place in our office on Avenue A on a Tuesday evening at 8 p.m. John Wilcock was there, a prized defector to The Other from the Village Voice, our designated competitor. I loved that idea. There were four new people in the room, none of whom was familiar to me, except for John.

“Okay, we’re here to buy stock,” Walter said. “Who’d like to go first?”

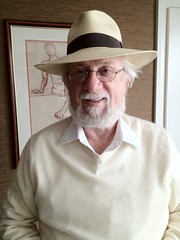

Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images Dan Rattiner, Walter Bowart (1939 – 2007), and

Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images Dan Rattiner, Walter Bowart (1939 – 2007), andbrothers Allen and Don Katzman.

I jumped right in. “I’ll go first,” I said. “I’ll buy $200 more.”

For some reason, I thought this was, like, bidding. I wanted to maintain my third ownership. So I would start and see how it went, and then see what I had to put in at the end to keep my stake at one third.

Others now spoke up. One person bought $100 worth; another bought $300. I tried to keep doing the math. I was at $800. Wilcock bought $100. Then there was a pause. Everyone had bought something except Walter.

“I’ll buy $1,000,” he said.

“Wait a minute,” I said. At this moment, I saw that my stake had been considerably diminished. And Walter was taking the major stake. “I’d like to buy more,” I said.

“It’s over,” Walter said. “We only go around once, man.”

Everybody smiled and nodded in agreement. I stood up angrily and walked out.

Well, I still had my own newspaper in Montauk and so the following week, I packed my things and prepared to head back out to the Hamptons to attend to it for the summer. But first I had to tell Walter.

“Look man,” he said. “I always knew you would go do your thing. Why be here and just be part of something in here when you’ve got your own thing out there?”

We hugged. “Hey man,” he said, “come back in the fall.”

But I didn’t. My only returns to EVO in the coming couple of years were for the occasional drop-bys to say hello to Walter, to see how he was doing. This also fed my fascination with the endless parade of people forever crowding into that office: the men in capes and rubber boots carrying walking sticks; the women in see-through blouses, black tights and miniskirts.

In time, Walter, too, moved on. He didn’t call me again until the summer of 1969, from Tucson.

“What do you think about you and me taking over The East Village Other?” he said. “We friggin’ own it.”

“Where are you?” I asked.

“Where are you?” he asked.

“I’m in East Hampton,” I said. “My newspaper is not just in Montauk now. I have four editions. One is Montauk, three in other towns in the Hamptons. The chain is called Dan’s Papers. And I’m married.”

“Busy guy,” he said. “I’m still in Tucson with Peggy, man. But you do know we own it. I’ve got 40 percent. You’ve got 20 percent. Count the stock.”

I had been following it from afar. It seemed to be thriving. Sometimes it was 60 pages long, and, along with the Berkeley Barb, was the largest and perhaps most famous underground newspaper in America. Its circulation was reputed to be 40,000 paid.

“I could do it in the fall,” I told Walter. “Or I could help you do it and get it started. I don’t live there anymore. But I don’t have anything else to do in the fall.”

“Plan on it,” he said. “I’ll fly to New York.”

“Say hello to Peggy for me.”

Peggy was Peggy Mellon Hitchcock, an heiress to the Mellon fortune. While still at EVO, Walter interviewed her for the paper when she was in New York City to give away to hippies some land she owned. Walter soon threw over Sherry Needham and moved to Tucson to live with Peggy on her ranch. They married a year later.

I looked forward to the fall. In the meantime, I worked hard. There were anti-war demonstrations in the streets of Southampton. A flag was flown upside-down in Amagansett and the man who did it was arrested.

When the appointed day arrived, Walter flew into New York from Tucson and I drove in from East Hampton. We met at 11 a.m. in a luncheonette on Second Avenue directly across from the Fillmore.

“What do you think?” I asked, motioning across the street to EVO’s offices above the theater.

“Nothing to it,” he said. “We’ve got all the cards.”

Walter still wore a headband, and now even had a ponytail and beard. But there was something very coiffed about him, maybe even blow-dried. It was the Peggy factor.

“You know my heart isn’t in this,” I said. “I’m doing it because you want to. You sure?”

“I’m sure, man.”

I looked across the street again. “Who’s running the place?

“Joel Fabrikant,” he said.

“You’re kidding.”

“I’m not. Jaakov Kohn, who used to write a column for us, is now the editor. But he doesn’t count. It’s Fabrikant.”

“What about John Wilcock?”

“Moved to California.”

I thought about this, remembering what Walter had told me on one of my short visits to the office. Fabrikant had been brought in because the paper needed someone “straight” to do the books. Well, straight by comparison. The first time Walter and I spoke about Joel Fabrikant, Walter was sitting at a large desk in a private office, dressed in a robe made entirely from an American flag. A strip of stars served as a headband to keep his by-then long hair in place.

“Let’s go,” I finally said, standing up. He got up and threw some money on the table for the coffee. Then we walked across the street and up the flight of stairs to the familiar and very busy office.

“Joel here?” Walter asked.

An old man with a white beard nodded his head in the direction of Walter’s old office. So we walked inside. And there was Fabrikant.

“Hey guys,” he said. “Howya doin’? Have a seat.”

We stood. “We’ve come to take the place over,” Walter said.

From Fabrikant, there was no response.

“Between us, we have 60 percent of the stock, man,” Walter said, motioning to me.

Fabrikant shrugged. “What do you want me to do?” he asked.

“Walter and I discussed it,” I said. “We want to go over the books.”

“Okay.”

“Go over them with Dan,” Walter said. “I’m going to talk to Jaakov.”

“Okay.”

Walter left, and Joel and I got started by going through things in filing cabinets. We looked at advertising orders, at bills, at bankbooks, at printing invoices, at sales commission calculations. It was a whole lot of stuff to go through and it was shockingly disorganized, which was what I had feared. But how disorganized could it be? I’d try to piece it together.

“Where are the income tax returns?” I asked.

“We have only done the last two years. Before that, we didn’t do any. That was before I got here. We were supposed to have done them, but nobody did them.”

I looked at the returns. For each of the two years, costs exceeded revenues. There was no profit. Also, the cost and revenue amounts remained unchanged during those two years, which I thought was strange. The paper had more pages with more advertising and circulation certainly seemed to be on the increase. It made me suspicious.

Two hours later, we took a break for a lunch of sandwiches delivered from a nearby deli. Fabrikant took some cash from a desk drawer to pay for it. We sat around, Fabrikant and I, and Walter, who joined us.

“How’s it goin’,” I asked Walter.

“Pretty good,” Walter said. “I had a meeting with the editorial staff. Kohn is not here today.”

Walter left and Fabrikant and I went back to our work, which at this point was beginning to give me a headache. Then Jaakov Kohn showed up and from the main editorial room, a yelling match broke out between him and Walter. There was the slamming of a door. Walter came in.

“Jaakov will be back tonight,” Walter said. “The paper is going out tonight.”

At about 3 p.m., there was an unforgettable scene. Payroll time. Fabrikant sat at his desk in the big office and I sat along one side and Walter sat on the other and people began to line up.

Fabrikant waited until almost a dozen people were quietly lined up at his desk across from him, and then he slid open a desk drawer, took out a cigar box, and opened it on the desk in front of him. It was filled with rows of bills – singles, fives, tens, twenties – and he would have a discussion with each person in front of him, make a decision, and then rummage around in the box, and then hand the person the money.

“I wrote two articles, one on the theater page, the other a profile of [Tuli] Kupferberg about his book,” a woman with blond bangs said. “Also, I was here for paste-up.” Fabrikant paid her.

“I did paste-up and delivery,” a young man said.

“Where were you on Thursday?” Fabrikant asked.

“I don’t remember, man.” Fabrikant paid him.

In this way, during the next 10 minutes, Joel Fabrikant paid more than a dozen people. Some went away grumbling; others went away happy. Nobody argued with him.

Shortly before 5 p.m., I went to use the bathroom. “EVO IS OURS,” read one scrawl in red. “MILLIONAIRE PIGS GO HOME,” read another in black. There was a bolt of lightning and rows of dollar signs.

That evening, Walter and I parted ways. He was staying in a fancy hotel, paid for by the credit card of Peggy Mellon Hitchcock, after approval of her trust fund lawyer, who monitored on behalf of the family everything Peggy did. I went to stay with my friend, who had an apartment on West 11th Street across from St. Vincent’s Hospital. Walter and I agreed to meet back at the luncheonette at 9 a.m. the next morning.

“Peggy called,” Walter said as we parted company. Her attorney had gone ballistic about the EVO bid.

“I’m trying to make sense out of the books,” I said. “But it ain’t easy.”

At 11 a.m. the next morning, we were back at EVO. I looked more closely at the figures showing the exact same income from circulation for two straight years even though circulation was clearly growing every week. People even talked about it: 26,000 last year; 40,000 this year. How could this be? That’s when Joel Fabrikant lowered his voice to explain.

“It has to do with the Mafia,” he whispered, and proceeded to talk about the distributor, the one I had arranged at the start.

“All through the first year I was there, the circulation kept going up. It was about 19,000 at first. Then it went up to 21,000, then 24,000. We would get these figures from the distributor when they would bring the money. It would be cash. They’d go to a newsstand, get paid cash, pick up the unsold papers, dispose of them, and then bring us the cash, less what they charged for doing the work. At 24,000, it stopped going up.”

“Did you talk to them?”

“I hinted at it. But they weren’t very forthcoming. I went to one or two of the stands and, yes, they were taking more and more each week. So then I thought I would ask the distributor about the money, and then I thought better of it.

“The funny thing is that each week, we would get the same printing bill from our printer – 24,000. So that’s what we paid. Nothing seemed to be amiss.

“One day, I decided to drive over to the printer to watch the paper being printed. The papers came off the press, got folded and bundled, then, when they got to 24,000 the presses were stopped. And that was it. The distributor’s delivery truck was backed up to the loading dock and the bundles were thrown in. Then the truck drove off. And so I left.

“But I didn’t leave. What I did was go out to my car and drive it around the block to the other side and park it there. Then, I walked back, but I stayed out of sight. And guess what?”

“What?”

“The distributor’s truck came back. And they started up the presses and they ran off a second press run of The East Village Other that we would have known nothing whatsoever about.”

We stared at each other for a moment.

“So what have you done about it?” I asked.

“I thought about it. And I thought this is a good way to get killed. And so what I did was call them up and I sort of let them know that I knew what was going on but it was all right. I said I understood circulation was 24,000 and that was just fine with me, so long as it didn’t go below 24,000 I would be very happy. They said that would be fine with them. And so that is what happened.”

Later that afternoon, Fabrikant, Walter and I were sitting in the office when Peggy’s attorney walked through the door. I knew right away, without even being told, that it was he. He was impeccably dressed in a light gray suit and without even saying a word to me or Joel Fabrikant, he walked in and over to Walter.

“I have to talk with you on behalf of Peggy,” he said. “And this guy, too.” He was pointing at me.

Fabrikant shrugged and left the room, closing the door behind him. We were now once again completely in charge of The East Village Other, a thriving underground New York City newspaper, is what I thought.

The lawyer didn’t even sit down. “I’m getting you two out of here, or Walter, anyway,” he said, waving his hand dismissively in my direction. He stopped. “Do you know what I found?” He waited for effect. “No? This company, this big little company has never, in all of its three and a half years, ever paid its withholding taxes. I have looked into it. There is no way that Peggy is going to be allowed to get involved in this in any way with her trust money. This is against the law. There are penalties. Huge fines to be paid. And you two own the majority shares in this? You could go to jail.”

And so we left.

Six months later, I sold my shares in The East Village Other to Donald Katzman, the twin brother of Allen Katzman, for the exact amount I had paid for them, $800. I went to his office in a shoe factory, where he worked as an accountant, and he paid me for my four shares of stock. And I washed my hands of the place.

Dan Rattiner’s two pieces for this series are adapted from the manuscript of a forthcoming book. He was one of EVO’s three founders and in addition to his business role, wrote and drew for the paper in its early months.

For more on “Blowing Minds: The East Village Other, the Rise of Underground Comix and the Alternative Press, 1965-72,” read about the exhibition here, and read more from EVO’s editors, writers, artists, and associates here.