Last month, The Local reported that Mary Help of Christians was on the market, as its congregation had dwindled to about 70 people. Meanwhile, on St. Marks Place, a church that came back from the brink of closing is, if not thriving, at least surviving. Father Krizolog Cimerman, who 19 years ago was charged with closing St. Cyril’s Church but works there to this day, said that 200 worshippers attended Christmas Eve mass last month. Two months prior, 150 people had celebrated the church’s 95th anniversary. But on Christmas Day and New Years, only 20 to 30 people showed – evidence that the Slovenian community that has long frequented the church is in a state of transition.

Slovenia, a small country of just 2 million people, separated from the former Yugoslav in 1991 and adopted the Euro in 2004. The land is coveted by tourists and locals alike, as sea, mountains, and vineyards can all be seen within the same afternoon. Because of its size, Slovenia had been occupied by just about every European country, from the Holy Roman Empire onward. Slovenians who migrated to countries such as Canada, Australia, and the United States starting in the mid 1800s made it a priority to retain their culture and language to pass along to future generations. This can certainly be said of the ones who ended up in New York, many of whom have considered the Church of St. Cyril a home away from home.

The brownstone church is long and narrow, with just enough room to fit one pew on either side of an aisle that can only accommodate two people standing side-by-side. American and Slovenian flags flank a modest altar overlooked by a large stained glass depiction of St. Cyril. There are no altar servers and often no choir. On a recent morning, however, five men descended from a loft for communion. Each donned a pair of slippers like the ones kept in every Slovenian home for guests and residents alike (cold feet is a fate worse than death).

Each Sunday after mass, members of the small parish stay and chat with each other in their native tongue – a tradition stemming not from their homeland, but that developed as Slovenians began moving further away from each other and seeing each other less frequently. A single pot of coffee is enough for everyone to have a small cup or two, as many Slovenians take theirs with mostly milk. Tins of homemade cookies are spread across a table.

“This is not only a church, but a cultural center as well,” said Father Cimerman.

The majority of Slovenians arrived in New York near the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. Many of them poor and unskilled peasants, they relocated to places with strong mining, foresting, iron and steel industries. Those skilled in straw-hat making (many of them from Domžale, where straw-hat manufacturing was the largest source of non-farming employment) settled in New York. Their trade served an abundance of Orthodox Jews living in the East Village, who covered their heads more often than not.

The following years saw a rapid increase of Slovenians in New York (most of them Roman Catholics), and the necessity for a church grew. The East Village was the most logical choice for a parish location, as the area, at that time, was the settling place for many large European groups such as Ukrainians, Polish, and most notably, Germans. As Slovenia was still part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, many of its former inhabitants understood and spoke German; until they had a church of their own, they made do with many of the German masses held each week. Eventually, so many Slovenians were attending German masses that they were recited in Slovenian as well as German.

For many years, the only thing preventing them from starting their own parish was the acquisition of a Slovenian priest. It took about seven years, from 1908 to 1915, for a contingent of priests working with the Franciscan authorities in Rome to finally agree to send a permanent priest, Father Benigen Soj.

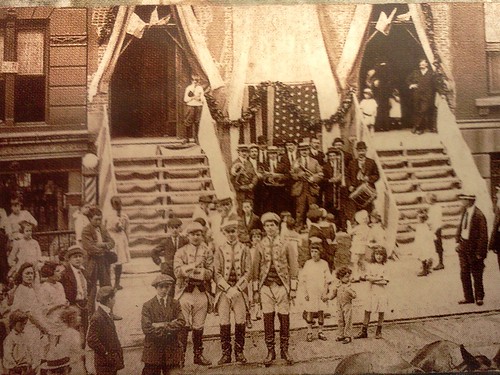

The next year, in January of 1916, the Slovenian parish was made official and titled St. Cyril Roman Catholic Church. A month later, the congregation purchased the brownstone it still uses today, at 62 St. Marks Place, for $19,000. A cornerstone was placed in the existing building, and inside of it, a roster with the names of the founding members, a few copies of newspapers, a short history of the church in Latin, and a small amount of American money. The very first mass was on Independence Day, Jul. 4, 1916, following a parade from the previous German church used by the Slovenians, the church of St. Nicholas, to the new church of St. Cyril.

Already at this point, Slovenians were leaving Manhattan for Brooklyn, lured by lower rents and larger accommodations. Around 1925, an attempt to start another Slovenian church in Brooklyn failed due to the death of the priest assigned to the task. Throughout the next 50 years, most energy went to preserving Slovenian culture, using the church as a home base. A language class was created, and saw its highest enrollment during World War II.

Nineteen years ago, Father Cimerman, now in his early 60s, was sent to St. Cyril by his superiors for the sole reason of shutting it down. “They told me to go for two or three years, and then to close it down,” he said.

After the threat of losing their church became more of a reality, the Slovenian community banded together and managed to donate enough money to keep the doors open.

Around this time, Slovenians began immigrating to the United States in mass quantities again. According to the U.S. Bureau of the Census, 123,631 people claimed Slovenian as their mother tongue in 1910. In 1990 that number was somewhat unchanged, with 124,437 people in the United States declaring Slovenian ancestry. However, in the 1990s the number rose dramatically: the 2000 census reported 176,691 people claiming Slovenian ancestry in the United States, a growth of nearly 42 percent, most likely due to the recent independence of the country.

On the 80th anniversary of St. Cyril’s in 1996, the Slovenian government granted $350,000 for the necessary renovations to the inside of the building, which was then over 100 years old. After an interior gutting and repairs to the roof, the only original architecture is the exterior and the set of stairs that lead from the hall in the basement to the main floor and then up to the choir loft and Father Cimerman’s residence.

Having just celebrated its 95th anniversary, St. Cyril’s is now in a state of transition. There is only one family that can say five generations have attended mass there; the rest are more recent additions, with one or two generations having been raised in the church. While there are not often more than a dozen or so people at mass, Father Krizolog said that it is not a fair representation of the community as a whole. “For the 95th anniversary, we had about 150 members of the community attend,” he said. “It’s hard to come here every week, but for big events, we all come together.”

Children of regular church attendees have moved to the suburbs and have become involved in their own activities, while their aging parents are less able to attend. However, Father Krizolog said the baby boomer generation is becoming more willing to trek into the city for programs that ensure their kids get the same cultural education that they did, at the same place.

The Slovenian language classes that were available through the church (currently on hiatus until a new teacher can be found) were a large draw to those outside of Manhattan, since such specific language classes are not widely available. “They would bring their kids and tell them, ‘This is where I went to church, and where I learned Slovenian,’” said Father Krizolog. “It is important to keep these traditions going.”

Every third Sunday of the month, after 10:30 a.m. mass, the community gathers to hear speakers talk about anything relating to Slovenian culture, be it food, dancing, language, tourism, or politics. After, everyone sits down to have lunch together, a traditional meal of Kranjska klobasa (similar to a garlic sausage), sauerkraut, and bread. The cultural hour was instituted in 1971, and with a few exceptions, has remained an influential part of the community.

As for the future of St. Cyril’s Slovenian Church, Father Krizolog is not certain. He said that as long as the young people remained involved, the community would keep going.

“I know I will be here until at least the 100th anniversary,” chuckled Father Krizolog. “The rest? That is in God’s hands.”