Meredith Bennett-Smith A hallway in the “permanents” wing (left) is much less colorful than one in the “transient,” or youth hostel wing.

Meredith Bennett-Smith A hallway in the “permanents” wing (left) is much less colorful than one in the “transient,” or youth hostel wing.Lisa Grossman has big dreams for a tiny space in the Whitehouse Hotel, one of the last of the old Bowery flophouses still sheltering permanent residents. The personal trainer, a Brooklyn native who now lives in New Jersey, hopes to open a fitness studio catering to the transient backpackers that pay $30 per night to stay in the boarding house’s 4-foot-by-6-foot cubicles. It’s just one of the recent improvements that former owner and current operator Meyer Muschel hopes will drum up business at the Whitehouse.

Ms. Grossman, a wiry, enthusiastic mother of five, said she has been training people ever since she began charging her dorm-mates at Syracuse University $5 each for workouts that consisted of Jane Fonda moves and track running. Seventeen years later, she tailors regimens to the individual needs of her clients. But Studio Fit will cater to the youth-hostel guests of the Whitehouse – many of them Asian and European tourists and students.

“A lot of people come there from all over the world,” Ms. Grossman said. “The rooms are so small, but the Europeans think they’re great. They want to see the city, and the city is a place to be fit.”

Meredith Bennett-SmithLouis D’Amato, 65, a former food vendor who

Meredith Bennett-SmithLouis D’Amato, 65, a former food vendor whosurvives off of disability checks, shows off his

cramped living space, rented for less than

$300 per month.

The trainer will need to be creative given the small size of the room, which was formerly used as a studio by the artist and poet Sir Shadow, a Whitehouse resident. “It’s a small space,” she admitted. “But we’ll have lots of toys. There will be a dip station, free weights, resistance bands, a pull-up bar and lots of mirror space.” Ms. Grossman also planned on holding classes in boxing conditioning, pilates fusion, and karate.

The Whitehouse opened in 1917, nearly a decade before the country’s first Pilates Studio came to New York City. When Meyer Muschel, a Columbia Law School graduate turned corporate attorney, bought the property in 1998, it was in desperate straits. Most of the 195 permanent tenants prowling the boarding house’s four floors were indigent. Three years later, Mr. Muschel opened up the Whitehouse’s 200-plus wooden cubicles to adventuresome tourists as well. Beds went for $28 per night.

While the number of “permanents,” as Mr. Muschel called them, has dwindled now, the prices and the ambiance have stayed mostly the same. Junkies and petty thieves no longer loll outside the lobby doors, but rooms on the renovated, northern half of the building are still rented out to young tourists and students for $30 per night, one third the price of similar-sized rooms at the polished Bowery House down the street. Permanent residents pay just $9.61 per night, a price that has remained stabilized for over a decade.

Meredith Bennett-Smith “Law and Order” plays on the common room television, one of the amenities aimed at luring tourists.

Meredith Bennett-Smith “Law and Order” plays on the common room television, one of the amenities aimed at luring tourists.Sitting in his pale yellow back office, converted from the skeleton of four rooms and a hallway, Mr. Muschel sported a growth of salt-and-pepper stubble and a custom-made cap emblazoned with the slogan “Everybody’s Entitled to My Opinion.” He was in mourning following the recent death of his mother, an Auschwitz survivor. His hands quivered slightly as he gestured animatedly.

“There is a fine line between a madman and a visionary,” Mr. Muschel said. “I thought I could help the Whitehouse evolve. I want to see it rise. It should be a plus in the neighborhood, not a blight.”

It hasn’t been an easy road. When he bought the old lodging house and started working on the Bowery, he was threatened and harassed by local miscreants, and once physically assaulted. As his attackers shoved him back and forth, Mr. Muschel remembers thinking it was a far cry from his former life at the law firm. Still, he stayed.

“I was concerned,” he said. “But I realized there needed to be someone, a presence in the building, in order to clean it up. There’s something magnetic about the Bowery. Everyone who comes here becomes very attached to it.”

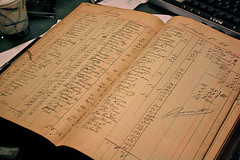

Meredith Bennett-Smith The ledger of former roomers at the Bowery’s Whitehouse Hotel dates back to 1918.

Meredith Bennett-Smith The ledger of former roomers at the Bowery’s Whitehouse Hotel dates back to 1918.In 2007, with the real estate market in a state of anxiety-inducing free fall, Mr. Muschel sold the Whitehouse to developer Sam Chang, who at the time planned to make a hardship application to the Landmarks Preservation Commission, in order to demolish the Whitehouse and replace it with a nine-story hotel. Gentrification was laying claim to many such landmarks.

“The flophouse community on the Bowery is disappearing,” Mr. Muschel said. “The entire neighborhood is changing.”

Mr. Chang’s plans were stymied, however, by the extension of the NoHo Historic District and the difficulty in obtaining the “certificates of no harassment” needed to evict the permanent tenants.

And so the Whitehouse lives on, one of the last of a dying breed.

Like most of the building, the lobby is decorated entirely in art by Sir Shadow, much of it for sale. (Mr. Muschel is also Sir Shadow’s agent.) Three computers make up the Internet café; an old Pepsi machine stands in the far corner. The hotel’s colorful new Website, launched in the first quarter of 2011, advertises last January’s “reopening” following “over $100,000 of improvements and renovations.” Those renovations are now beginning — albeit slowly — to extend to the permanent tenants’ side of the building.

Mr. Muschel said his hostel visitors were not so different from his permanent renters: “Young travelers have the same needs as indigent people — both just want a clean, safe, inexpensive place to stay.”

And Ms. Grossman believes they could also use a place to work out, no matter how small. “You can make a gym out of two feet,” she said. “[Or even] out of a soup can.”