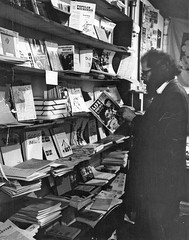

Out this month, poet Ed Sanders’s memoir of the 1960s, “Fug You,” serves as a veritable who’s-who of the characters of the beatnik, hippie, and yippie scenes: Splitting his time between playing with his satirical rock group the Fugs (first at local spots such as the Bridge Theater at 4 St. Marks Place and then around the world), publishing one of the East Village’s most influential alternative journals, and operating the iconic Peace Eye Bookstore (first at 383 East 10th Street and then at 147 Avenue A), Mr. Sanders crossed paths with the likes of Andy Warhol, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Abbie Hoffman, and Timothy Leary, among others. Jonas Mekas and Harry Smith inspired him to experiment with underground filmmaking, and another close friend, Allen Ginsberg, joined him in attention-grabbing stands in support of drug legalization, pacifism, and first amendment rights.

Interspersed with Mr. Sanders’s memories of publishing everything from mimeographs (many of which are reproduced in the book) to some of Ezra Pound’s “Cantos” out of his “Secret Location” on Avenue A (at one point, the $27.49-a-month apartment was raided by the F.B.I. as they sought a roommate rumored to have knowledge of Lee Harvey Oswald) are his recollections of recording with the Fugs, defending himself in court against charges of obscenity, and also defending himself on television against a drunk and surly Jack Kerouac, who had grown conservative in his later years. (“During the show,” writes Mr. Sanders, “I was very tempted to mention his daughter Jan, who’d come to many Fug shows. I remembered how the owner of the Astor Place Playhouse had come on Jan and a Fugs guitarist making it on the drum riser one midnight.”)

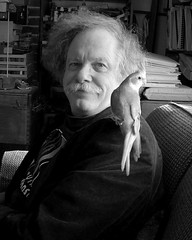

The Local spoke with Mr. Sanders, who now lives in Woodstock, over the telephone earlier today.

As you put this memoir together, did you find gaps in your archives due to some of the police confiscations you describe in the book?

I have a vast archive, and it’s pretty well organized – I keep a lot of files in bankers’ boxes in my barn out back. The only things they confiscated were my underground films, which they took in their entirety from my secret studio on Avenue A. And when they raided my bookstore in early 1966, they took some publications, but not all of them.

When you started the book, did you have any inkling, as you wrote about the many demonstrations that you participated in, that your story would be so relevant now in light of Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring?

I didn’t do it to be timely. I just thought I had a varied career and I had met an enormous panoply of Americans, Europeans, writers, artists and fellow rock people, so I just dipped into those memories and into those files and old leaflets. I didn’t mean to be au courant. The book is out to the public right at a time when protest has come back like it does every 30 or 40 years, going back to the revolution of 1805.

What do you think of Occupy Wall Street, anyway? As the 70s set in and you began working on a book about the Manson family, you seemed to be gaining a new appreciation for authority.

I think [Occupy Wall Street] is great. I’m a little too creaky to go camp out somewhere, but I certainly appreciate their struggles. There are such a vast variety of issues now that I think they’re correct in not focusing on one specific issue, but to have 100 or 200 issues they bring up.

You were involved in quite a variety of issues yourself. Where do you think you were most effective?

I guess I’m proudest of the ability to take a stance for a right cause in the face of great hostility and to use the non-violence of Gandhi and Dr. King to present controversial issues. I raised my banners and helped exorcise the Pentagon and the grave of Senator McCarthy, took part in the Chicago riots of the summer of ’68, tried to get into Czechoslovakia to sit in front of Soviet tanks as part of the Fugs tour. And I was part of a generation that helped expand constitutional freedoms.

Occupy Wall Street has reminded us that police work can sometimes still come up against the work of the press. Back then, was there an us-vs.-them mentality as far as the Ninth Precinct went?

I was never really specifically bothered by the police in the Ninth Precinct, but during the Summer of Love in 1967, they had a captain down there who did a lot of what I thought were unconstitutional drives against crash pads and urban communes, and virtually stifled them. The police were pretty vicious against smoke-ins and certain activities in Tompkins Square Park. The only problem I had was with one sergeant who raided my bookstore in ’66 and kept showing up at our concerts. During one in Tompkins Square Park, there was a bomb scare and he came backstage, looking through our bags. I think most cops probably just want to uphold the law as they see it and don’t want to reach out to squelch personal freedoms.

One gets the sense while reading this book that the East Village was a very tight-knit community back then. It didn’t take long for you to befriend some of your heroes, like Allen Ginsberg.

It was all contained in a few blocks where everybody could live, because that’s where the rents were affordable thanks to rent control. There were a lot of bars and bistros and cafes and hangouts and art galleries and stores where you met. I was part of what they called “the mimeograph revolution” so I was always always printing flyers and pamphlets, and setting up poetry readings. I was pretty active in my milieu of writing, art, and music, and we had a lot of benefits for people arrested for pot or to help raise money for issues. There was a sense of camaraderie and community among the partisans in the 1960s. You could still get an apartment for $20 or $30 a month – the rent control didn’t start corroding until the 70s and 80s.

But things got darker as the 70s began. In the book, you write about the infamous murder of Groovy, who briefly ran Peace Eye as a sort of community center.

In my mind, it began in 1969. There was a lot more violence in the street. We lived on Avenue A and 12th and there was a tailor across the street. Some kids came in and [bashed] his head in with a brick and ran away. He died. There was a woman late in 69 who was just stabbed to death in the street outside our house. She was screaming for her life as she fell down to the cobbled streets. I put it in my book: It could be late 60s paranoia, but after Nixon came into office, there seemed to be a lot more heroin on the Lower East Side. There were a lot more muggings. I was mugged. That’s one reason we decided to move.

Peace Eye was clearly a tremendous asset to the community, much as the St. Mark’s Bookshop is considered to be these days.

I called it a scrounge lounge. I always had places for people to sit and chew the fat, and I always had a free mimeograph – I printed lots of street leaflets for all kinds of groups. For a while I was helping with the underground railroad to help soldiers escape the war and get up to Canada. They’d come into my store and leave their uniforms and we’d give them clothing and they’d head out and I’d have to figure out ways of discarding their uniforms in nearby waste cans. A lot of people came in and out of the store in both locations. It was a kind of hangout.

What did you think of that other pioneer in the underground press, the East Village Other?

They did a good job. They advanced design – they had Bill Beckman and others who helped design their format. They did some investigations. We had some good times. I moved Peace Eye Bookstore in 1968 to the old E.V.O. office on Avenue A because they moved over to Yoko Ono’s loft on Second Avenue. We were friends. Walter Bowart [a founder] was a bartender at Stanley’s which was the prime watering hole for the East Village art, poetry, revolution crowd in the late 60s.

It’s funny, the blog Ephemeral New York just linked to a New York Times item from 1964 that referred to the changing demographic at Stanley’s. Did you feel that the bar and the neighborhood around it became more upscale while you lived there?

Stanley’s always stayed pretty funky. I did notice the East Village going upscale. First of all, there was no East Village – we called it the Lower East Side, and the Village Voice and E.V.O. started calling it the East Village for commercial reasons. There were more tie-dye shops and the Psychedelicatessen on Avenue A where you could buy psychedelic candles and acid. A lot of commerce developed on the Lower East Side and it became more of a tourist mecca. People tended not to live there forever – it was more of a transient neighborhood. You got a pad while you were in college and then moved on after a couple of years.

Do you go back to the neighborhood these days? What do you make of it?

I always stop in and sit there in Tompkins across from the old bookstore, which is now a coffeehouse [Cafe Pick Me Up]. It’s all right. It’s nice to go in May or April when the fruit trees in Tompkins are still in bloom. There are still a lot of rats in the park. I take part in the Ginsberg festival every now and then, and I’ll walk around the nabe, go to Odessa.

As an N.Y.U. graduate, what do you say to people who think it’s the scourge of the neighborhood? Is it responsible for ruining the neighborhood by flooding it with students, as some have said? Or has the East Village long been a neighborhood of young transients?

It’s been that way since the overcrowding after the War of 1812 when they first made those tenement buildings. It’s been a transient phenomenon. I don’t feel a resentment against N.Y.U. – it has expanded, like a lot of these colleges. N.Y.U. is expanding and it’s gotten more upscale. It was a little more proletarian when I went there, and they’ve raised their standards quite a bit. It’s still a desperate-search-for-some-meaning-in-life college and it’s all right.