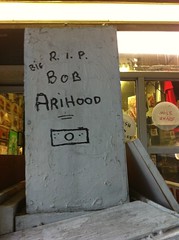

Tonight at 7:15 p.m., friends of Bob Arihood and admirers of his work documenting the daily life of the East Village will gather at Lucy’s, with a candlelight vigil to follow at 8 p.m. at Ray’s Candy Store. Today, his body is being returned to his hometown of Lafayette, Indiana. According to Leslie Arihood, his younger brother, funeral arrangements have been tentatively set for Sunday at the Soller-Baker Funeral Home.

In the days since Mr. Arihood was found dead in his apartment, bloggers have paid tribute to him, but few personal details have emerged about the man who Wah Mohn, 21, a Columbia student and acquaintance of the photographer, called a “super loner.”

“What made Bob special was that he listened to people,” said one of the three men who found Mr. Arihood’s body on Friday, adding that Mr. Arihood was more inclined to hear someone’s life story than to tell his own.

It was just that kind of warmth that drew people to him as he canvassed the neighborhood, and last week, his conspicuous absence from his usual local haunts around Tompkins Square Park was cause for concern. So was the surgical appointment he missed on Tuesday.

Chris Flash, the publisher and editor of the underground newspaper The Shadow, said that the surgery was intended to alleviate the chronic pain in his lower back, said to be the result of a police beating he took in 1988 during Tompkins Square Park riots (the officers accused in the matter were acquitted the next year). Mr. Flash said that Mr. Arihood, whom he met in the aftermath of the riots, had recently started complaining about chest pains that he thought were related to asthma.

Asghar Ghahraman, the owner of Ray’s Candy Store — more commonly known as Ray Alvarez — was one of the last people to see Mr. Arihood. “He came in and said he didn’t feel well and he wanted to go home,” recalled Mr. Alvarez, adding that the blogger’s regular order was a bagel with cream cheese.

On Wednesday, a foul odor caught the attention of a 49-year-old elementary school teacher who lived upstairs from Mr. Arihood for almost 30 years. When Mike, a friend who did not wish to give his last name, came looking for Mr. Arihood on Friday, it became apparent that something was wrong.

“We called the police,” said the upstairs neighbor, who also preferred not to be named. “We waited for 30, 40 minutes in the hallway, and we said, ‘We can’t just stand here. We have to know.’” With the help of a neighbor across from Mr. Arihood’s storefront-style apartment, the two men broke down the door and entered single-file — the only way to navigate the cluttered space — to find him lying on his loft bed. According to the city medical examiner’s office, he died of high blood pressure and heart disease.

Before coming to New York, Mr. Arihood grew up on a farm in Lafayette, Indiana, where his parents rented a house for $15 per month. “It had an outhouse, but it kept the wind out,” said Leslie Arihood, 62, the deceased’s younger brother. Now a scientist emeritus after a long career as a hydrologist in the water resources division with the United States Geological Survey, Leslie recalled Bob fondly. “He was so talented that he gave me an inferiority complex when we were growing up,” he said. “He was good in sports, popular, good in school, good with his hands.”

In high school, Mr. Arihood showed an interest in science and mechanics. He once fixed up a motorcycle and re-chromed it, and then let his younger brother ride it to school on his last day of classes. He played basketball and football, winning a MVP award as a running back during his senior year. Though he continued to play for two semesters at Purdue University, he was never much of a sports fan.

“It could be that sports was his challenge as a kid in school and when he got out of school he dropped it and went onto the next thing,” Leslie theorized. The only thing his brother couldn’t do well, he said, was tame his independent streak and join the establishment.

After leaving Lafayette for bigger cities like Chicago, Denver, and New York, Mr. Arihood rarely returned to visit. His brother’s wedding in 1972 and his mother’s funeral, 30 years later, were exceptions. “He decided that Lafayette was boring,” Leslie said. “I think he found that in New York City you could be successful and get something accomplished by taking pictures of life going on in the East Village.”

Bob Arihood’s artistic sensibilities were honed at a young age. His brother still has a painting he made in elementary school of a cardinal sitting on a tree branch. “I remember thinking that it was a great cardinal,” he said.

At Purdue, he earned a BFA in painting and sculpting, but found his calling only after switching mediums to photography — a passion he never outgrew. Though he would complain to his brother about the difficulties of making a living as a freelance photographer and blogger, he stayed in the industry out of love for the work.

According to a brief obituary in the Daily News, Mr. Arihood worked in engineering, construction, and design in the 1990s. Constanza Marre, an acquaintance who works in a photography studio, recalled Mr. Arihood mentioning after the Fukushima disaster that he was familiar with nuclear plants. Richard “Handsome Dick” Manitoba, the owner of the eponymous bar, remembered Mr. Arihood mentioning an earlier stint working at the Fillmore East, but knew little of his professional life beyond that. “I always wondered, how can he stand on the corner in front of a candy store for 20 years,” he said.

Fellow photographer Clayton Patterson is among the many who appreciated Mr. Arihood’s dedication. “Knowing what’s national is something you’ll never touch, feel, and see, but the neighborhood is real. Being familiar with what’s local is really what’s most important in daily life,” he said. “He gave a sense of importance to that corner.”

“He was always walking around with that big camera,” said Mr. Mohn. “He was like Rorschach from ‘The Watchmen’ — he always had the gritty information on the neighborhood.”

“It wasn’t until now that I see what he accomplished out there,” said Leslie Arihood of his brother’s work in the East Village. “I [once] thought, ‘Oh, gee, what a waste. He’s got so many ideas, he’s bright and talented, and he’s not making money,’ but now I see that he was accomplished in presenting cases for people in need and helping get somebody’s sad stories out. That’s really a life accomplishment. He was doing something good there in his free time, and he was doing it for free. He stood up for people who couldn’t stand up for themselves.”

“He really loved this place, and the people,” said Mr. Arihood’s upstairs neighbor. “There are still a few people like him left here, but it’s only a matter of time before they’re also gone, and this neighborhood becomes like every other New York neighborhood. Guys like Bob really gave this place a sense of identity that’s slowly but surely being lost.”