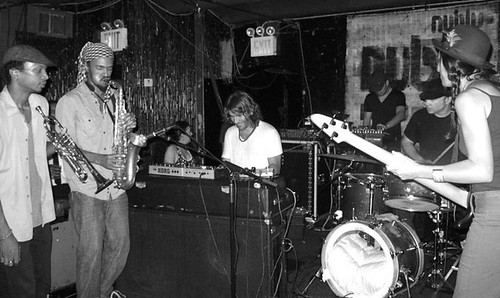

Vladi Radojicic Ilhan Ersahin, the owner of Nublu, plays the keyboards at the club’s temporary space on First Avenue alongside Shawn Pelton on drums and Tina Kristina on bass.

Vladi Radojicic Ilhan Ersahin, the owner of Nublu, plays the keyboards at the club’s temporary space on First Avenue alongside Shawn Pelton on drums and Tina Kristina on bass.The owner of Nublu, the hip club on Avenue C that was shuttered for being within 200 feet of a Jehovah’s Witnesses Kingdom Hall, told The Local today that a return to his Avenue C location was not imminent, and that it was possible he might have to look for a new space outside of the East Village.

Ilhan Ersahin, who opened the club in 2002, said that he thought it was unfair that he lost his liquor license after years of being in business across the street from the house of worship.

“How can they come nine years later and then say I made a mistake?” said Mr. Ersahin, 45. “It can’t be just up to me to investigate whether a place is 100 percent a house of worship.”

Nublu’s liquor license was revoked in May after an anonymous caller alerted the State Liquor Authority to its proximity to the Jehovah’s Witnesses building — a violation of state law.

Mr. Ersahin, who just returned from a tour overseas, said he has consulted with three lawyers regarding his dilemma. One of them said that there is still hope for him to regain his liquor license; the other two said that the best he can hope for is the right to sell just wine and beer.

Then there is the route that the Knitting Factory, Luna Lounge, and other displaced venues have taken: Brooklyn.

“I haven’t even put my mind to moving to Brooklyn or [elsewhere in] downtown Manhattan, but maybe that’s what I’ll have to do,” Mr. Ersahin said.

While he tries to decide how best to proceed, Nublu has temporarily set up shop on First Avenue in the basement of Lucky Cheng’s. The move has not been good for business.

“It’s not like just the business is losing – artists are losing too,” Mr. Ersahin said. “We made money with liquor and then invested in records. Instead of making 10 records a year, we might make four now.”