With the threat of another recession looming large in the markets, I can’t help but recall another steep downturn, long ago; a terrible time when work was nearly nonexistent. By the summer of 1979 most young people were broke as a joke. But this was not true of a friend of mine, who will hereafter go by the name of “M”

Until M busted a move to help me out, I didn’t have a single prospect. But I had been told, in hushed and reverent tones, that M possessed a secret method of raising cash. M by and by revealed what it was, an absurdly simple scheme, diabolically clever. It involved selling all the joys and sorrows of the world for nothing more than pocket change.

It was the world of the newsboy.

M insisted that this was the world for me, despite my doubts. Desperation steeled my resolve, and the next morning I accompanied M downtown to the World Trade Center, where all city newsboys reported for duty.

Our day began at 7:00 am, when a truck from the New York Post dropped wire-bound papers down to the curb. A deposit was then handed over to the bosses. This was so that I wouldn’t lose heart and just walk away. That should have told me something right there. They sent me first to the Financial District, on a corner shrouded in darkness and woe. It was a lonely existence, where a blind man shaking dimes in a cup was making better money than I was. Only one thing could have possibly saved me: cuteness.

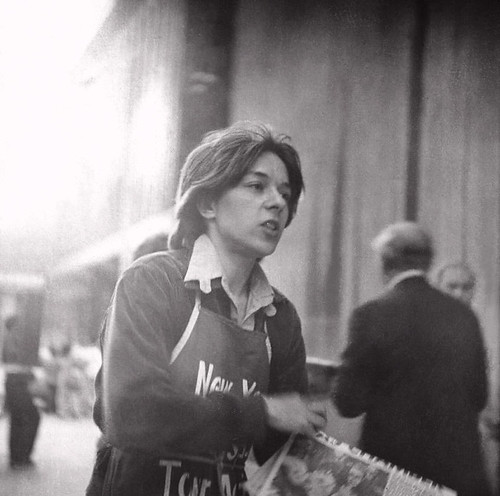

Cuteness sells papers, in case you hadn’t guessed, and it must be said that the very best newsboys were all cute as hell. One winsome youngster named Victor sold 700 papers on any given day. The kid was cute. My friend M was also quite cute, and was making money hand over fist. The Wall Street traders saw something rare in their cuteness, an antidote to all the poison and evil that polluted their souls. In the newsboys’ shining appeal, the traders themselves became transformed, rejuvenated, cleansed. For these gnarled old lions, a newsboy like M stood as the very emblem of goodness; a son they never had, cute enough to counter the disappointment they felt for their own ugly, bratty, unlovable children.

I had to admit that I did not have the guile, charm, or moppet appearance required to attract their attention. I was completely insufficient in cuteness. Indeed I was homely, and there was little love on the street for me or any of the other not-so-cute newsboys. And so we prayed together, us homely ones, for the outbreak of war, scandal, and murder most foul. This is because the best possible thing when selling a newspaper, apart from cuteness, is a blockbuster headline: something lurid, gripping, and dripping with gore.

Then came the day our wildest dreams came true. Splashed across the paper that morning was the full-page shot of a Brooklyn mobster all splattered with blood. It was a classic rub-out à la “Godfather,” with café chairs and spaghetti all over the place.

“Check it out!” Victor howled, and showed off a headline to make any one of us happy. The papers flew right out of our hands. And how I remember the evening that followed, when all of us newsboys ate like kings.

But that was hardly the norm, and before long this thing began to eat at my gut. How could I hope to compete with such cuteness, with the likes of newsboys like Victor or M? We can’t all be born loveable. What a cruel twist of fate! Even more galling was the ugly truth of the matter, because M, the vaunted son the buyers never had, wasn’t even a boy.

That’s right. You’ve got it: M was a girl. M was a fraud.

With her cherubic face and tousled coif, slim and petite as she was, as long as she avoided tight tees and skirts, she could easily get away with this brazen masquerade. And in doing so she had a distinct advantage, because what girl ever broke a sweat trying to be cute? It was downright unfair.

One sad day, down at South Ferry, my bad luck took a turn for the worse. A gale-force wind blew in off the harbor. It tossed aside trashcans and knocked over some trees. Afraid for my life, I ran into the subway, but then thought twice and went back for my papers. I had barely reached the top of the stairs when the hurricane lifted them up, up, and into the sky. Imagine seeing all of those papers — my papers — like mad grey birds, circling the eye of the storm.

So, there went my deposit, and my career. I trudged up Broadway back home to the East Village, my papers hung from every flag-pole and cornice. I can’t even remember the headline that day. It couldn’t have been too very exciting; and that about says it all, I guess.