I walk into B&H Dairy and squeeze myself along the narrow aisle between the tables lining the wall and the stools lining the counter. The small deli restaurant is loud with people, the radio and the clattering of plates and bowls.

As usual, Raffi, the cook and maître d’ of sorts, an immigrant from Pueblo, Mexico, has a few things going at once on the grill: an omelet, a grilled cheese sandwich and some breakfast potatoes. While it cooks, he covers the food with a large aluminum foil container, which he then covers with a plate—he has a system in place. Up and down the counter are couples and friends laughing or in eye-locked huddles.

“You!” Raffi puts his hands out in a simulated hug. He wears a black Yankees cap turned to the back.

“Hey!”

“Where you been?”

“Oh, you know, around. I don’t come to this neighborhood that much anymore. I’m so glad you are here. I came in not too long ago and a guy was here I’d never seen before so I thought maybe you quit.” I throw my backpack under the counter on the tiny dirty ledge, and take out my notebook and pencil.

“Naw, I didn’t quit. That was my boss.”

“What’s he like?”

“The boss? He’s an Egyptian guy.”

“How long has he been the owner?”

“Not long. Before it was Polish guys.”

“And before that?”

“Jewish guys. Lots of guys! There’s been about a hundred owners!”

“Wow. How long has it been here?”

“Since 1942. And too many owners.”

He moves down to an older Latina lady with a big plastic flower in her hair and a long gray braid sitting at one of the tables against the wall. All along the wall above the tables are framed displays of rows and rows of miniature blue, green and red pitchers. It took two years before I noticed them. Raffi hands her a paper plate stacked with their signature homemade challah bread from behind the counter. She takes it: “Gracias.”

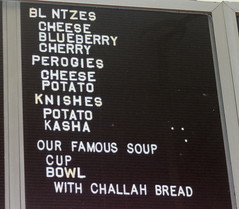

All of the specials of the day line the wall above the grill opposite the counter on laminated cards tacked up with tape in different pastel colors. In the summer they have cold pink borscht with dill, just like my grandmother’s.

Raffi sees me writing and knocks on the counter.

“You see this counter? The countertop is from the 70’s.” He reaches his arm over and under it. “But underneath it is the one from the 40’s. They just put this over it.” He turns around and ladles some borscht into a small bowl.

“What do you want?” He lifts his chin at me.

“Oh, a hot chocolate would be great.”

He turns around, takes out a Nestlé packet from the box, drops the powder into a mug and fills it with hot water from the coffee machine.

“They say the menu hasn’t changed since it opened, only the prices.”

“Do you like the food?” I ask him as he puts some bread on the grill.

He widens his eyes in seriousness. “I love it.”

“You do?”

“Oh yeah. The soups!”

“The soups. Which?”

“I like the split pea. The lentil.” He plops a tomato soup in front of a kid in a baseball cap. “Sandwich is coming,” and he nods his head to the grill where the sandwich is cooking under a plate.

“Who makes the soups?” I ask.

“The Polish lady comes a couple times a week to make it. Oh no, I made a mistake!” He runs over to his omelet and flips it with a spatula. “That’s not right.” And he starts it over again. “Forgot to put the tomatoes and the spinach in with the eggs, man!”

In comes a gaggle of NYU girls all in different colored tights. They take the big table in the back. All of them order macaroni and cheese, except for one who orders soup, and “extra butter” on her bread.

“Extra butter? Wow,” Raffi shakes his head. They burst into laughter.

An older guy with gray hair creeping out from under his beanie squeezes past me. He wears an oversize dark sweater and pants that are too big for him.

“Hey,” he says.

“Hello.”

“Whatcha doing, writing a book?”

“You could say that.” He has pink warts all over his right cheek. His eyes are so blue and his pupils so small he looks like he is blind. I can’t really tell where or what he is looking at. His teeth are brown, pointy shards. I am scared of his breath but he doesn’t smell like anything.

“I been coming here since the 70’s.” He slides into the stool next to me and puts his bag down.

“Wow. What was it like in the 70’s?”

“There used to be all Jewish guys who worked here.” He looks behind the counter as if they are still there. “They would all laugh and make jokes. They were all like him.” He looks at Raffi. “Except Jewish. Now it’s Mexicans who work here. You know, that’s how it works. Whoever is at the bottom rung of society runs the place. He keeps this place together. You gotta have a guy like that running your business. There was this one Jewish guy I remember who worked here. He could throw his voice. He was a ventriloquist. He would throw his voice all over the place and confuse the hell out of everybody! And when the guys would tip big, the guys behind the counter would call him “jumbo jockey.” You know like how you bet big on a jockey. You following me?”

“Yeah.”

“Okay, well anytime someone would tip big the waiter would say jumbo jockey real loud and everyone working would stop what they were doing and bow as the guy left! Every last one of them would bow and go, ‘Jumbo Jockey!’ It was all Jewish guys then. Then Puerto Ricans. Now Mexicans. That’s the story of old New York.” He turns to the front door and looks out the window. “And out there, used to be all Vaudeville. Vaudeville theaters. And other places like this. Tons of places like this. Now this is the only one.”

“Yeah.”

“There was always something going on on the street. Music, performances, people being crazy. But it was dangerous like you wouldn’t believe. I used to run up and down the streets late at night just to keep myself from getting harassed by some numb nuts criminal. But it was fun. Before the Vaudeville, it was Yiddish theaters. All up and down Second Avenue here. This is one of the only places that is still around from them days!”

“So you’ve been coming here all this time?”

“Oh yeah. They got the best soup.”

“Raffi said they never changed the menu. I guess that means it’s always been vegetarian.”

“No, no. It’s not vegetarian. It’s called B&H Dairy see?” He points to the menu. “They serve fish here and eggs too. Just no meat. Which is great for me because I’m vegetarian. The Jewish guys who started it they wanted a place that was kosher, do you know what kosher is?”

“Meaning a rabbi blesses it and—“

“No, no! People always get this wrong. You don’t gotta have a rabbi blessing it for it to be kosher. Just no meat in where they serve dairy also.” He pauses. “See that grill?” He points to the grill.

“A-ha.”

“No bacon, no hamburger has never been made on that grill. Not ever. Most places they say they got vegetarian items but they cook their veggie burgers on the same grill that they cook their burgers and crap! That’s why I like this place. They still got the best soup in New York, too.”

He takes out a dollar and leaves it on the counter. “Well it was good to talk to you. My name’s Joe by the way.”

“Lana.”

“Take care Lana. Night Raffi!”

“Hey, where’s the Jumbo Jockey?” Raffi says smiling.

“Eh, wise guy.” He looks at me and blushes.

“Hey man, that’s 15 percent!”

Joe shuffles out of B & H with his back hunched and his raggedy coat hung over his arm. He looks old and young at the same time. I stare after him wondering where his home is, what it’s like.

Raffi shakes his head at me.