The City of New York has known the influence of many powerful men, one of whom was a man of the cloth named Archbishop John Hughes. He had, since his arrival in 1838, aligned himself with the unassimilated Irish immigrants in lower Manhattan. This Ulster-born prelate rallied them in the face of abject discrimination, (such as “No Irish Need Apply,”) yet played on their fears whenever he could. Hughes was highly ambitious, and gladly courted controversy in the press. His letters to the editor were always signed with a cross, which with a flick of his pen looked a whole lot more like a knife. And because of his fearful countenance and violent temper, reporters began to call him “Dagger” John Hughes.

That Hughes himself was a deeply bigoted fellow would not be a difficult point to prove. He regularly published his racist diatribes, and exhorted his disdain for abolitionists in numerous sermons. He whipped up his largely Irish congregation with dire warnings of freed black slaves traveling north to steal their jobs, and they heeded his every word.

By 1861, even Abraham Lincoln was terrified of Hughes, and courted his favor at the outbreak of war. He dearly wanted the “Fighting Irish” on the side of the Union, and Dagger John was flattered that Lincoln would call on him with hat in hand. He therefore wrapped himself in the flag and bid his parishioners to do the same.

But two years later his sympathies were clearly on the side of Dixie, a sentiment which New York’s Irish took to heart: the Union army was thick with poor Irish men. Daily, thousands of them stormed the Confederate hoards, who with breathtaking skill cut them down like rabbits. The Union ranks began to thin, and so a conscription lottery was decreed for July of that year, 1863, America’s very first wartime draft.

A man of wealth could, for $300, buy his way out of the draft. A poor Irishman however, who had never seen $300 in his life, was bound to fight for a country he wasn’t even born in. Ironically, had this Irishman remained loyal to Victoria the Queen and refused the oath of citizenship, he would have been exempt from the Draft, just like the black man, who also held no citizenship in this Land of the Free.

Instead, on July 11, 1863, these sworn citizens stood before the Office of the Draft in New York and watched helplessly as a basketful of tickets was mixed all together. From that paper flutter was drawn the first names: the roll of doom.

After Mass that next Sunday, gangs of Southern agents emerged from their lairs to mill among the city’s faithful. There, finding men in fear of their fate, they found it easy to incite them to riot. The next morning a great crowd milled outside the office of the Draft, their pockets lined with stones. And as the first names were called aloud, volleys of these came sailing through the windows. Once the doors were broken down, the place was set afire, despite the cries of those who lived above.

How the city’s black population became the focus of hatred during that violent outburst is a question that still haunts us up to the present. Up and down the length of Manhattan, any blacks within reach, even women and children, were beaten and lynched. Two hundred children made a harrowing escape from an asylum for black orphans which the mob had sacked and burned to the ground.

Yet Horace Greeley of The New York Tribune was convinced that he knew the reason why. To his mind, if any one thing could possibly be cited, it was the undisguised racism of Dagger John Hughes, and his vituperations against the war. He had just finished admonishing him for “not teaching his flock better treatment for the city’s Negro residents,” when the violence first took hold. Hughes thoroughly detested Greeley, and never missed a chance to take him out for a roll in the mud. This time, however, while he verbosely hammered out his wordy reply, the city exploded.

With the riot fully out of control, on July 14 Greeley again blasted the cleric for denouncing abolition and Union, and for provoking the cause of the riots. Characteristically, Dagger John spat copious venom in his published rebuttal, which concluded with a limp appeal for calm and order, as if it were an afterthought.

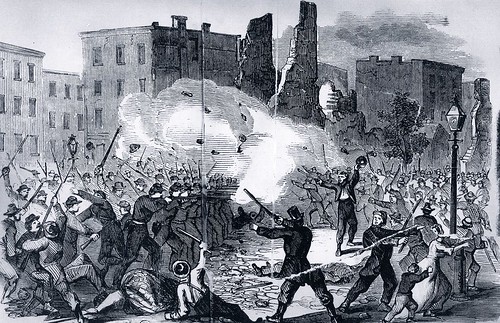

But it was much too late. Like the corpse that hung from a neighborhood tree, set afire to illumine the hellish way forward, his words blessed the night that would swallow a city. Catastrophe quickly followed. Union troops now marshaled on the streets of New York. At the drop of the sword they leveled volleys of musket-fire into the face of the mob. Around 11th Street and First Avenue the rioters regrouped and then marched uptown, where battle-hardened men stood ready to face them. The crowd refused the call to disperse, and so they aimed, fired, and cleared the street with artillery. The carnage was appalling, but it did not end the riot.

New York’s Governor Seymour now begged Hughes to appeal to the mob. This groveling played well with old Dagger John, and on July 16 placards went up inviting everyone to come to his home to hear him address the matter at hand. The next day, five thousand people gathered under his balcony. Hughes placated them by quoting the Word, and finally urged them to return to their homes. He didn’t mention the murders of twelve black New Yorkers, or the hundred others who lost their lives, nor even of the city that now lay in ruins, but said: “I don’t see a rioter’s face among you.” This gesture, however, had the desired effect, and after five days of riot, the crowd walked away.

The traffic then returned to the streets, and the dead were removed so the living could pass. Hughes was widely hailed as peacemaker and savior. He joyfully accepted these accolades, which only served to seal his damnation. For it was thus made apparent that if the Archbishop was able to end the riot on Friday, he could very well have ended it Monday. Sizing up all the suffering and loss, people had to wonder why Dagger John Hughes hadn’t spoken up sooner.

Correction: July 31, 2011. An earlier version of this article mistakenly associated Horace Greeley with the New York Herald. He was actually the creator of the New York Tribune, which merged with the Herald after Greeley’s death.