News that an old friend is seriously ill is sure to darken the day. Concern and sympathy are mingled with hopes for recovery as well as thoughts of one’s own precarious grasp on life. Those of us who love books to the point of distraction grapple with a similar set of emotions when a fondly visited bookstore shows signs of slipping away.

It can’t happen; it shouldn’t be allowed; and what about me? Where else can I go?

Robert Contant who, with partner Terence McCoy, is co-owner of St. Mark’s Bookshop on the corner of Third Avenue and Stuyvesant Street, blames his customers somewhat for the store’s current frailty. He has seen them browse through the store, then scan the barcode of a likely purchase with their smartphone only to discover they can order it more cheaply from Amazon.com, or from other online vendors which don’t bear the real estate and staff costs of running a brick and mortar store in a well-trafficked city neighborhood.

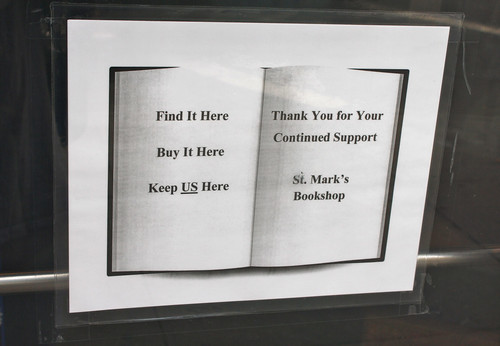

Mr. Contant hastens to explain that he speaks in sorrow, not in anger. “It’s hard to tell people not to save money,” he says, especially these days. “We’re not blaming them. We’re not trying to be punitive.” Nevertheless, anyone who has seen a book on the shelves of St. Mark’s, then purchased it online, should feel a pang of guilt reading the notice recently posted in the store window: “Find it here, buy it here, keep us here.”

The simple supplication, borrowed with permission from Harvard Book Store in Cambridge, which finds itself in a similar plight, brings home starkly the growing threat to local bookstores. Book sales have declined across the board in almost catastrophic way, Mr. Contant told me. The publishing business is panicked because no-one has yet found an easy way to make money out of e-books.

Will books go the way of CDs, where record companies lost support from a customer base which felt ripped off to begin with? “Everyone knows it costs a few cents to make a CD. Charging $18 for one was just outrageous. Although I liked Tower Records” Mr. Contant consoles himself by remembering television’s challenge to the movies. The demise of the cinema had been predicted, but it survives in various forms.

His last thought in posting the warning sign is to alienate customers. He doesn’t want it to give the store that “going out of business look.” Rather, he sees it as a way of reminding customers that by going online to make purchases they threaten a valuable resource. “You can’t browse online,” he explained. Even if you scour reviews, it’s hard to keep up with new releases. “People don’t make the connection that, if the store didn’t exist, they wouldn’t know about the books.”

In support, he cites evidence from some treasured customers. St. Mark’s has a strong specialism in critical theory. “Richard Foreman, the theater guy, came in the other day and asked me ‘Who’s the new Badiou?'” Bob Herbert, recently retired as a Times columnist, also comes in. Recently he bought an anthology of contemporary French philosophy and admits to Mr. Contant that he wouldn’t have found “this or that book” without the opportunity to browse the shelves.

Cuts at the store have already been drastic, from the salaries Mr. Contant and Mr. McCoy draw, through staff lay-offs, to growing gaps in the stock. “We used to have 10 copies of popular books in overstock. No more. We have more and more face-outs” — the sales tactic of displaying a book face-on to the customer which also eats shelf space. The Web site is doing fairly well, with customers signing up for niche e-mail newsletters listing new releases in strong areas like critical theory and poetry.

As ever, the root problem seems to be paying the rent. The store was opened 33 years ago at 13 St. Marks Place. After 10 years it moved to the nearby landmarked building at number 12. It was approached by the Cooper Union to be the commercial tenant below the student residential accommodation in its current spot. There are still eight years left on the lease, but Mr. Contant feels that Cooper Union would rather the bookstore leave and be replaced by a tenant with deeper pockets.

“We’re trying to meet with them,” he said, “but it hasn’t happened yet.” He is putting out feelers to customers who also have local political connections. Mr. Contant hasn’t given up, but sometimes sounds despondent. “We are dumbing down our society in a very alarming way.”