An early photo of a Native American trail from the Inwood section of Manhattan Island. Photo by W.L. Calver, originally published 1922.

An early photo of a Native American trail from the Inwood section of Manhattan Island. Photo by W.L. Calver, originally published 1922.Plans to pedestrianize Astor Place and expand Cooper Square Park, which were presented to Community Boards 2 and 3 on January 6th, are moving toward approval from the city’s Public Design Commission. A few wrinkles must be smoothed out, however, before the blueprints can be handed over to a contractor. Perhaps the most interesting community petition made thus far is that an old Native American trail, which ran through the area, be memorialized in the new design.

The Local thought that in light of the request, this might be the perfect time to look at the oft-forgotten historical presence of Native Americans in the East Village.

Once upon a time, Manhattan was a remote offshoot of North America with dense forests full of wildlife, open fields overgrown with rich grass, and bountiful harbors teeming with oysters, lobsters, and fish.

According to Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, tribes of Lenape Indians set up camp on this bountiful land, which they called Lenapehoking or, “where the Lenapes dwell,” more than sixty-five hundred years ago. They moved about frequently in groups of roughly 200 people at a time, hunting deer and wild turkeys, fishing, and foraging for nuts and berries.

Some fifty-five hundred years later, they had established more static communities thanks, in large part, to agricultural advancements. When Europeans arrived in 1524, approximately 15,000 Lenape Indians of various tribes lived in what is now New York City.

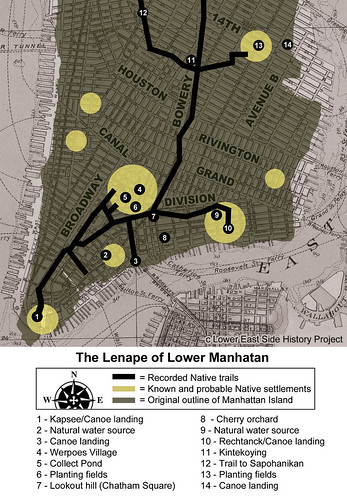

The Canarsie tribes settled in two locations near our modern-day neighborhood, according to the Lower East Side History Project. A village called Shempoes was located between Tenth and 14th Streets along Second Avenue and another called Rechtanck was situated near Clinton and Montgomery Streets along the coast of the East River.

What we now call Astor Place used to be named Kintecoying or, “Crossroads of Three Nations,” and was a powwow point for the Lenape tribes of Manhattan. The trail from the Shempoes village began around St. Marks Church-in-the-Bowery and cut diagonally through Ninth Street and St. Marks Place to Astor Place. The Rechtanck’s trail followed the Bowery and Fourth Avenue exactly and extended beyond Astor Place, where it served tribes located further uptown. Sapohannikan tribesmen from the West Village hiked down Greenwich Avenue to Washington Square Park, where they turned eastward toward the meeting place.

At a sacred oak tree, where the branches of the trails converged, the Lenapes traded with each other, exchanged news, and held spiritual ceremonies and tribal councils to settle disputes.

The Lenapes lived peacefully—in 1670, Daniel Denton scornfully wrote, “it is a great fight when seven or eight is slain.” The women of the matrilineal societies farmed beans, maize, squash, melons, and tobacco, cooked, raised the children, and tended to the communal longhouses while the men hunted and fished.

Land ownership was a nonexistent concept in Lenapehoking. Mr. Burrows and Mr. Wallace tell us in their book that, “if the land ‘belonged’ to anyone, it belonged to the inhabitants collectively” and they “had no authority to dispose of it by sale, gift, or bequest.”

Nevertheless, as legend goes, the Dutch bought Manhattan from the Lenapes for 60 guilders (often quoted as $24) in 1626. Whether this is fact, myth, or exaggeration is a debate that historians have engaged in for more than a century and a half and not one that we at The Local are prepared to settle.

What is definitely true is that the Dutch colonized the island and took ownership of the land.

By 1628, all but two or three hundred Lenapes had been driven off the island by rival Iroquois tribes from the north or killed by unfamiliar European diseases.

Nearly four centuries later, only 0.4 percent of Manhattan’s population is of Native American descent, according to an American Community Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau between 2005 and 2009. Andrew Berman, executive director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historical Preservation, pointed out in a letter to the Department of Transportation that Astor Place is one of the “only reminders of the Native American settlement” in New York.

According to Craig Chin, a spokesman for the Public Design Commission, current plans indicate that new benches and trees will line the roadbed that closely follows the old Native American trail. “Other options that acknowledge the Trail are still being considered,” Mr. Chin said, “such as constructing it out of a different paving material, but that hasn’t been finalized.”

Mr. Chin said the Design Commission hopes to hire a contractor this summer and begin construction early in 2012.

L. Buddy Gwin, executive director of the American Indian Community House in New York, wishes the Native community had been consulted during the process.

“Too often the First Americans are the last Americans to be included in the discourse of change,” Mr. Gwin said. “We remain the invisible minority in our own land. At first blush the current proposal seems reasonable enough. However, a sober second look reveals that it falls far too short. There needs to be something more substantive done to prevent the final obliteration of the vestiges of the First American from their historic and ancestral neighborhoods.”