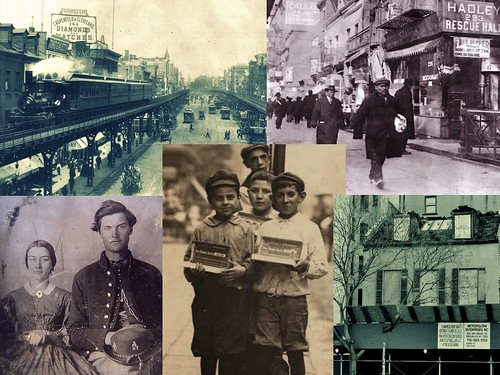

Clockwise from top left: (1.) Bowery Elevated Train, circa 1896; (2.) Bowery near Bleecker, circa 1915; (3.) 35 Cooper Square in February this year; (4.) Boys on the Bowery selling chewing gum, 1910; (5.) A Union enlistee of the New York 86th Regiment and his betrothed, circa 1861. All images courtesy Library of Congress, except (3.) lower right, photo illustration by Tim Milk

Clockwise from top left: (1.) Bowery Elevated Train, circa 1896; (2.) Bowery near Bleecker, circa 1915; (3.) 35 Cooper Square in February this year; (4.) Boys on the Bowery selling chewing gum, 1910; (5.) A Union enlistee of the New York 86th Regiment and his betrothed, circa 1861. All images courtesy Library of Congress, except (3.) lower right, photo illustration by Tim MilkLocal historian Tim Milk recalls dark episodes which never quite extinguished the charm of 35 Cooper Square.

They could hardly believe the fellow, wanting to go back to his regiment. Especially considering what he had seen: the rout of the Union at the bloody battle of Bull Run. There, the heroic Lieutenant John S. Whyte, who had refused to leave his wounded commander, fell into Confederate hands. But in a recent prisoner of war exchange, he was returned home to his kith and kin in New York.

But he did not wish to retire with honors. Indeed, he was keen to “return to the fight,” he said.

And so his pals shook their heads and dragged him down to the Marshall House, a tavern at 391 Bowery, an address we know today as 35 Cooper Square. There they presented him with a sword and a sash in an affair both touching and festive. After a grand hurrah, the champagne flowed like a river long into that night of March the 21st, 1862.

This I found in the archives of the New York Times, in a curious walk down that ancient lane, the Bowery. From out of each door came someone with a tale to tell which, except for these old papers, and poor relics like 35 Cooper Square, would otherwise have vanished, lost in time.

“Time,” Stephen Hawking once said, “…whatever that is.” Even he doesn’t pretend to know. As the so-called future, it is but a mere concept. As the past, it holds everything that has ever happened, and leads all the way back to eternity. There it washes up on distant shores for no apparent reason, except perhaps for our return.

186 years ago, in 1825 or so, a timber and brick “federal-style” house went up at 391 Bowery, along with a similar structure right next door, like sister and brother, the seeds of a row. It was a neat design, with a storefront below and quarters above. Through their shy dormers she and her twin watched many a sunset together, and noticed with interest the ceaseless flow that passed below their eaves.

By 1900 her brother had vanished and she found herself wedged between two taller buildings. It was the modern, vertical city coming to be. Tall iron trestles sprang up from the ground, to lift the Elevated Train up into the sky. This was a great feat of engineering, but it made the strip along Cooper a dark and disconcerting location. It became, if you will, a scene-set worthy of the most lurid film-noir.

On July 3, 1907, the good old house was open as usual, now operating as a pawn shop. Rudolph Oberlander broke a sweat there that day, as he felt the burning gaze of detectives Susillo and Horton. They had both lain in wait to bust him for pawning antiques he had stolen from his uncle. It was a mere indication of what lurked in the shadows.

In the heat of summer 1912, a young man entered 35 Cooper, now a cigar store. He had murdered before, and he would murder again. George Clark had a thin nose, close-set eyes and an undershot jaw. A swagger was his usual style, and after shooting a jeweler to death down on Delancey, he boarded the elevated train and descended right here to look for more trouble. Clark shot the salesman, Maxwell Katz, three times for no reason. But this time his victim leapt upon him like a demon. Throughout the shop they tussled, blood flying and spattering everywhere. Clark finally pulled himself free, and busted out, gun in hand, into the sunlit square. A little boy saw him make his escape and guided the police to where he had hid in a basement.

Past the two Wars and the Great Depression, from the late 1940s and into the 60s, painters and poets were drawn to 35 Cooper, during a particularly fertile time for the arts. When the elevated tracks were finally torn down, Cooper Square was revealed for what time had made it: a squalid backwater. In the years that followed, it was the artists, indeed, who revitalized both the Square and the moribund East Village.

In our own post-modernist era, breathless developers descended en masse. The Cooper Hotel went up, like an invasive species engorged between orchids. 35 Cooper thus became famous as the “Little House that Could,” persisting there despite all odds. The hulking Hewitt building then appeared up the street, and if you were to stand and look down its length onto the new hotel, you like anyone else would have to conclude that 35 Cooper was doomed.

The future, which we all know is merely a concept, demanded it.

It had survived 186 years of change and adversity. It was the longest standing show on the Square, only to fall to someone’s conceit. The developers must be powerful indeed, to destroy such a colorful, historic, and marvelous thing.

But can they do as well in replacing it?