Dan Glass Saxophonist Darius Jones and Kirk Knuffke on cornet lead the Kirk-Jones Quintet duiring a performance at the University of the Streets, the cultural center that has thrived for four decades.

Dan Glass Saxophonist Darius Jones and Kirk Knuffke on cornet lead the Kirk-Jones Quintet duiring a performance at the University of the Streets, the cultural center that has thrived for four decades.A tumble of snare snaps and clarinet wails escaped the second-floor windows above the restaurant 7A on a recent Saturday night. A garbage truck and police car replied with a snort and a whoop. Jazz was happening up there, in a place called the University of the Streets.

Neighborhood folks know the tagged glass door, the kitchen-bright vestibule on East Seventh Street and maybe the lighted sign mounted next to it But few know what is on the six floors above, where a karate dojo, artist studios, and until recently a pigeon coop, operate along with a small amphitheater that hosts an open jam session that has taken place every Friday and Saturday night since 1969.

It’s a remarkably consistent run by nearly any measure, but all the more impressive for taking place here in the center of the in the East Village, which has been on an express track of socioeconomic change for the past 40 years.

“This place is an institution,” said Robert Anderson, 57, a Saturday night house bassist who is built like a light heavyweight. “And we’re trying to get it back to how it used to be, back when those guys was comin’ down – C-Sharpe, Barry Harris. Monk used to come through here, Dizzy – everybody used to come through here.”

The second floor space where the contemporary counterparts to those giants of jazz gather is named after the longtime director of the University of the Streets, Muhammad Salahuddeen. With its battleship gray floors, bright plastic school chairs, and spare décor, the amphitheater feels more like a small community college classroom than a downtown jazz venue, which is its charm, as well as an indication of its past. In its heyday, the University of the Streets was a thriving DIY community center that provided local residents with job skills training, arts workshops, and informal classes from drama to radio and television repair.

“We had plumbing, electricity, and carpentry shops, fully loaded,” says Saadia Salahuddeen, 60, who took over as executive director after her husband, Muhammad, died in 2007 at the age of 77. She added that those workshops were part of his effort to reach out to people and try to help them learn skills that could help them survive.

Mr. Salahuddeen was director of the University of the Streets since the beginning, but the project was originally an outgrowth of the “Real Great Society,” formed in 1965 by Puerto Rican ex-gang leaders Chino Garcia and Angelo Gonzales, along with Fred Good, a self-described “rich white kid” of Belgian descent. The idea was simply to improve the community and try to keep kids out of trouble.

“It was a play on Lyndon Johnson’s ‘Great Society,'” said Mr. Good, who moved to North Carolina in 1981 to pursue art and raise a family. “We kind of became media stars.”

It was the age of radical chic. Mr. Garcia and Mr. Gonzales embarked on speaking tours that brought them to cities across the country. Mr. Good helped secure grants. By 1967 the University of the Streets was going strong, matching people who wanted to learn with those who had something to teach.

But money, race, and competing self-interests resulted in rifts. Mr. Good left to work on several other community programs, while Mr. Garcia went on to create the Chartas / El Bohio Community Center, a community center housed in an old schoolhouse on East Ninth Street. Mr. Salahuddeen, however, stayed on at the University of the Streets.

“He was very torn,” said Mrs. Salahuddeen. “Between being a professional musician and being a community leader.” She added that he created the jam sessions “so he would always have that outlet, for him and his musician brothers.”

But not all of the programs at the University of the Streets are musical. If jazz is the bebopping heart of the place, then Grand Master Wilfredo Roldan, head of the Nisei Goju-Ryu dojo on the third floor, is the muscle.

“I grew up in this place,” Mr. Roldan, 59, said recently, adding that he began learning karate there at the age of 14. He went on to get a master’s degree in physical education and worked as a New York City public school teacher for 27 years. Now, he said, he is trying to instill in neighborhood youths the same sort of discipline and streets smarts that he learned at the dojo decades ago.

Mr. Roldan went on to work as a bouncer in nightclubs and helped junkies go cold turkey. At one point, he said, he met “jazz royalty” in the mid-90’s, when a friend brought him to the apartment of Duke Ellington’s son, Mercer, and about the old times when the center was packed on the weekends.

“While the Village Gate was the place to go listen to jazz, after the musicians did their gig, they came here to jam and hang out,” Mr. Roldan said, a tone of reverence in his voice.

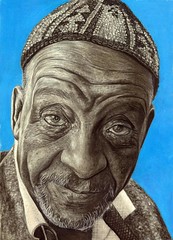

Zoe Matthiessen An illustration of Muhammad Salahuddeen, the longtime director of the University of the Streets who died in 2007 at age 77.

Zoe Matthiessen An illustration of Muhammad Salahuddeen, the longtime director of the University of the Streets who died in 2007 at age 77.Things at the University of the Streets quieted down around the late 90’s. Mr. Salahuddeen was riddled with scoliosis and arthritis, Mrs. Salahuddeen said, and he suffered a lot of pain in his last decade. And the crowds that came to the University of the Streets were no longer as large as they had once been Her husband was never skilled at business or book keeping, she said, and the University of the Streets began struggling.

Mrs. Salahuddeen said that she is in the process of selling the building, although she is planning to strike a deal that allows her to hold on to the second and third floors for 15 years. She said that she hoped the curated concert program, begun in October, will help rekindle interest in the center and bring in badly needed funds.

One of the guest curators for concerts held at the center is Steve Swell, a trombonist and composer, who has played alongside Buddy Rich, and collaborated with Anthony Braxton. Well known in the jazz world for his high-metabolism playing style, Mr. Swell said that the second floor jam sessions could be the longest running in the city.

“From 1969 to now, I don’t think there’s any place that’s been as long-lived as University of the Streets,” he said.

And his thoughts on the role of music sound as if they could have been formed decades ago, during the days that the members of the Real Great Society helped found the University of the Streets.

“If we learned how to interact better socially,” he said. “Which music gives us the ability to do, then we’d be creating a more enlightened society than what we have.”

It costs $5 to play or watch the 11:30 p.m. to 2 a.m. jam sessions, and after a set by the Kirk-Jones Quintet one recent Saturday night, the theater cleared out but for the house rhythm section, three visiting musicians, and an audience member with a bagged beer. Someone suggested a tune, and Mr. Anderson, the bassist, said, “Nah, I’m not feeling it. Let’s just groove for awhile, you know, rhythm changes.” And with that, the sticks, strings, and keys send music across the room and out the second-floor window, adding their notes to those of the street.