John Penley’s circuitous journey to the world of community activism in New York City began with a single question.

It was 1984 and Mr. Penley had just finished a year in jail after charges arising from his role in a protest at a South Carolina nuclear plant.

“When I got out of custody, they gave me a $100 bill and a bus ticket and asked me where I wanted to go,” recalls Mr. Penley, who is 59. “I said New York and that was it.”

Since his arrival in the city, Mr. Penley has been a stalwart in the community of grassroots activism – aligning himself first with the squatters movement and most recently organizing a protest Sunday against plans to restrict concerts in Tompkins Square Park.

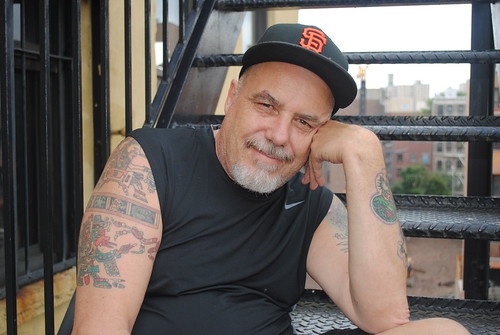

Mr. Penley, a respected amateur photographer – he describes himself as an “anarchist photojournalist” – is donating images from his years in the East Village to NYU’s Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives. He recently spoke with The Local about his activism, his photography, life in the neighborhood and his frequent criticism of NYU.

Why did you choose to live in the East Village?

The neighborhood was not under control by the city or the police; it was the residents, whether they were doing it right or wrong. I liked that it was its own world, completely out of control. A lot of people thought it was bad that there was anarchy, lawlessness and drug dealing but on the other hand there was incredible art, music, and cheap rents.

How did you end up with the squatters in Tompkins Square Park?

At first I went and lived in a homeless shelter on East Third Street. But the shelter had such horrendous living conditions – drugs, robberies, it was crowded, dirty, smelly and dangerous – that it seemed worse than any of the jails I’d been in. At that time, Tompkins Square Park was open 24 hours a day and so I hooked up with the squatters and squatted in various locations.

When did you begin to notice changes in the neighborhood?

Gentrification came soon after the squatters were kicked out of Tent City. All of a sudden, the Lower East Side arts scene got famous and a whole bunch of people with money came in and rented store fronts and opened up art galleries. Then the increased rents forced out he original tenants, store-owners, community centers and radical groups. Now you don’t see art, music or anything culturally valuable coming out of the crew that’s living down here.

You’ve long been an outspoken critic of NYU. Why?

I think NYU has been one of the beachheads of forced gentrification of the neighborhood. When they put the first dorm over here, people were climbing over the fences as they tried to stop it. NYU has put in a large number of students who really don’t have any connection to the neighborhood but they have a higher disposable income than most of the people from around there. I wouldn’t mind so much if I ever saw the students participating in the political or social scene rather than walking around the neighborhood wearing the same kind of clothes, chattering like mindless idiots, or drinking. They don’t really care about the neighborhood.

What about the value of the education imparted at NYU?

New York is a multicultural city. You find everything here but you don’t find everything at NYU. Students are getting an education, but not a cultural one. If only they could help some of the bright kids from the projects. None of the Puerto Ricans who are being forced out of this neighborhood have any hope of getting an education.

What is your reaction to having been described as a leader of the protests in this neighborhood?

I’m a hillbilly from North Carolina; I’m not a leader of anything. I couldn’t get a bunch of drunk punks to get together and go to an open bar with free booze. The only reason I got anything going with the protests is because people shared my anger against the changes in the neighborhood.